The physical cash issued by central banks is one of the most private forms of money, but most central banks are looking at the feasibility of replacing, or at least supplementing it with a digital equivalent, central bank digital currency (CBDC). However, all electronic payments systems, by their very nature, leave an audit trail of transactions and central banks, in spite of notionally being independent in many countries, are ultimately an arm of the state or sometimes a supranational entity like the European Union. One of the key concerns about CBDC questions is, how do you avoid CBDC being turned into a system for the state to spy on the public and their purchases?

Fear of governments’ ability to more closely monitor spending, and even control what people can spend money on, has provoked pressure groups and politicians such as Governor Ron DeSantis, of Florida, to campaign against CBDCs. Some claim these fears are overstated if not irrelevant, particularly in developed countries where cash has mostly been replaced by electronic payments already and there are many ways for law enforcement (with the correct legal permissions) to track people via access to their bank accounts, mobile phone records and CCTV.

In spite of the outrage of a vocal minority of people, a more fundamental question is, how much would people really care about the state having even more information about their spending habits? Not to mention the potential absence of more private alternatives. Surveys or public consultations can provide insights into feelings of the public about privacy (from the state) in electronic payments. Both add value though public consultations may not be representative of public opinion as a whole and surveys on theoretical subjects (such as a potential future CBDC) may not reflect how people would act in reality. Transport for London (TfL), the body that controls London’s public transport, has unintentionally created a great natural experiment regarding how much people care about the privacy question and how willing they are to sacrifice privacy for factors such as convenience.

There are currently four main ways that Londoners and visitors can pay for travel on public transport: paper tickets, season tickets (stored on electronic stored value cards called “Oyster” cards), “pay-as-you-go” Oyster cards (where value is stored on a card but reconciled back to a central electronic record held by TfL) and contactless debit and credit cards (where the cost of travel is debited from a bank account or charged to a credit card).

Pay-as-you-go Oyster and contactless cards are essentially both forms of digital money, even if restricted to only paying for travel. They do, however, have very different degrees of privacy. An unregistered Oyster card, paid for with cash and topped up using banknotes and coins offers almost complete privacy. No one need know where a member of the public has travelled to (except if their image has been recorded by CCTV or they carried a registered mobile phone). Registered pay-as-you-go Oyster cards require more personal information but there is no validation that any of the personal information provided is true. So they have somewhat less privacy. An unregistered contactless credit or debit card provides TfL with minimal information about the identity of the user but with legal authorisation, law enforcement can easily obtain the user’s real identify and considerably more personal information. A registered contactless card provides the least privacy of all. Around 70 per cent of Oyster cards are not registered, so, in general, pay-as-you-go Oyster cards offer considerably more privacy than contactless credit or debit cards (whether registered or not).

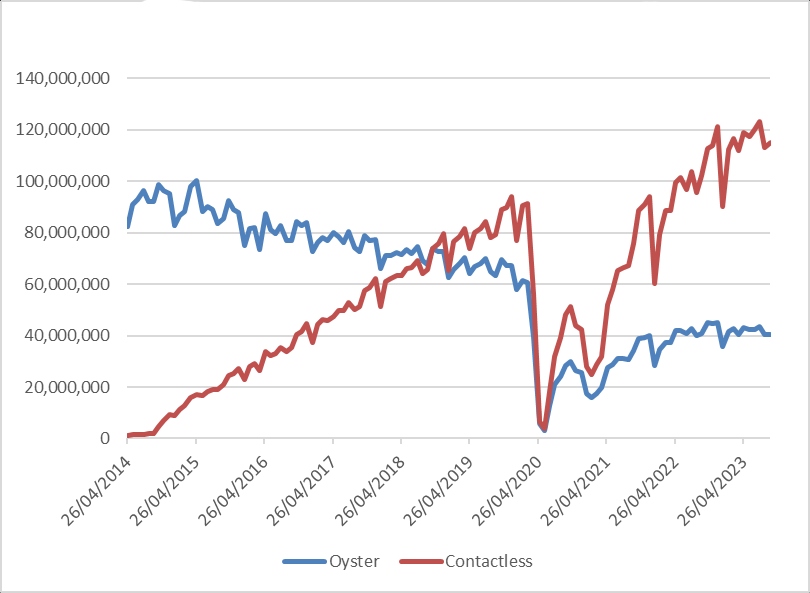

Following their introduction in 2003, Oyster cards quickly and largely replaced paper tickets but what does the data about the relative usage of Oyster versus Contactless since 2014 tell us? How much effort are people willing to make for privacy versus the inconvenience of having to periodically load funds onto an Oyster card? Looking at the data from TfL, the answer is clearly very little. Apart from the blip of the COVID lockdowns, usage of contactless debit and credit cards for bus and tube journeys has grown from close to zero in 2014 to around 120 million journeys per month. Meanwhile, use of pay-as-you Oyster has seen a 50 per cent fall in terms of total number of journeys (see below).

Figure 1. Oyster pay-as-you-go vs contactless, total journeys (number of journeys per four-week period)

Source: Transport for London (here and here)

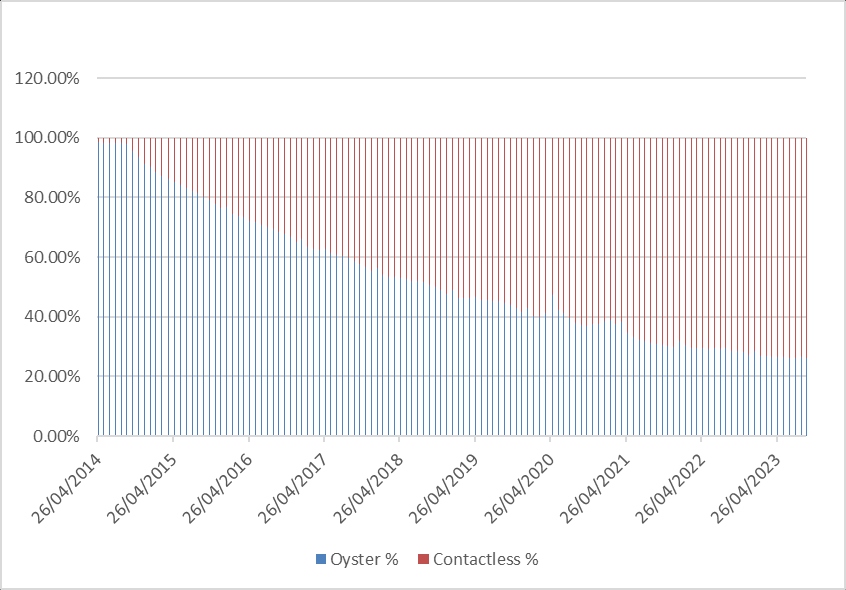

As a percentage, usage of contactless credit and debit cards for pay-as-you-go travel has grown from nothing to 73 per cent in less than eight years (see below). The trend suggests that use of Oyster for pay-as-you-go will almost disappear in a few years.

Figure 2. Percentage of pay-as-you-go journeys

Source: Transport for London

It could be argued this sacrifice of privacy for convenience might be because people are not conscious of the privacy benefits of unregistered Oyster cards compared to contactless credit or debit cards. However, this is certainly indicative of the value most people place on convenience rather that an additional degree of privacy.

This data could be taken to conclude that the privacy concerns of some regarding CBDCs are overblown, but before drawing that conclusion there is another lesson to be learned from London’s public transport network. In 2013, TfL carried out an analysis of Oyster versus cash usage on buses and found the principal reasons for using cash were “forgetting to top up an Oyster card, or forgetting or losing an Oyster card”. Having to top up an Oyster card is considerably less convenient than paying directly from a bank account (via a debit card) or using a credit card for which the user is already settling a monthly bill. So who would bother to top up the CBDC wallet to pay for things for which they could already use their credit or debit cards?

Privacy fears may not turn out to be the greatest obstacle to the rollout of retail CBDCs. Central banks are already struggling to find compelling reasons for people to use CBDCs. What if the simple inconvenience of using CBDC is enough to stop widespread adoption? The evidence from TfL suggests that convenience is a very powerful force in retail payments. Something central bankers should not underestimate.

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock.

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.