After two decades of increasing fragility and a brutal evolution of environment, the economic and political world is looking for new ways to counteract fragility. We are living through a rare period where history is written from day to day.

If inflation in consumer goods does not fall back below the 2% target, the euthanasia of the Western rentier will continue. [Al Jazeera]

In physics, a disturbance, or stress, is represented by the pressure wave of a shrill scream in the night similar to the one below:

Below is an economic wave portraying the quarterly GDP growth of the United States over the last twenty years. To the left is the 2008 crisis; to the right, the Covid-19 crisis.

Clearly, for the last three years, the world has been under severe stress. First, there was the global spread of the coronavirus pandemic worldwide. Then, all the developed countries began printing money uncontrolledly, causing a devaluation. Next, as a result of this devaluation, there was inflation with the increase in the prices of consumer goods all countries except for mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Brazil. Now, we have the Russian-Ukrainian war, which has been de facto internationalised by the Western economic sanctions policy against Russia. Economic sanctions require the target country to be isolated, hence the necessary geopolitical involvement of the whole world.

Antifragility

The concept of antifragility was invented ten years ago by Nassim Taleb – professor of risk engineer, mathematical finance trader, author and scholar – highlighting that a very large proportion of people, nations, economic systems, and even financial assets react negatively to disruptions. They lose value or utility when stressed. Stock prices fall, for instance, when market volatility spikes.

Some systems, though rare, react in the opposite direction: they benefit from stress. These systems are said to be antifragile.

The meaning of fragility is common sense. It characterises almost all the products we manufacture, from automobiles to computers, and chemicals to clothes. With rare exceptions (e.g. the vintage trend), the value of these products reaches its peak upon leaving the factory. They then lose value throughout their lifetime due to stresses, shocks and temperature variations until eventually, they are thrown away and replaced.

But the mistake would be to consider that a fragile living organism or economic actor is a weak actor. In fact, the opposite is often true. It is the dominant ones who lean irrevocably towards fragility, quite simply because their domination provides them with a rent, and they seek to protect their rent. The protectionist temptation is strong, and even irresistible.

The example of the Kodak company is emblematic. Founded in 1880 in Rochester, New York by George Eastman (hence the name “Eastman Kodak Company”), the brand revolutionised the world of photography through multiple inventions: x-rays, medical imaging, colour film, polaroids, etc. In 1975, its Research and Development department invented the first digital camera. The company patented it… and then hid it for more than 15 years in the bottom of a drawer until 1990 when Canon and Nikon reinvented the process, triggering the end of Kodak.

Why did the company deprive itself of a major discovery? Simply because it was dominant in its sector and benefited from a considerable rent that it did not want to jeopardise: 85% of camera sales and 90% of film sales. The digital camera meant the end of film.

Fragility is not weakness but rather conservatism and, more fundamentally, over-optimisation about one’s environment, rendering the system deeply efficient if nothing changes – and dreadfully inefficient if the world changes.

66 million years ago, the fragile animals on earth were the gigantic dinosaurs. Some weighed as much as 30 or 50 tons. It was impossible to dislodge them. Eventually, an asteroid known as the Chicxulub impactor hit the Yucatan peninsula and set the earth on fire. It left a crater with a diameter of 180 kilometres underneath the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

Over-optimised in a suddenly changing environment, dinosaurs lost their metabolic efficiency and disappeared, replaced by the small, agile and antifragile mammals that managed to adapt to the new environment.

We are the heirs of these small nocturnal mammals, still physically weak but intellectually agile, and we owe our conquest of the planetary ecological niches to a big rock.

Antifragile or fragile do not mean good or bad. It depends on the circumstances. They describe evolutionary strategies relying either on the stability – or instability – of an ecosystem. Nothing is worse for the living world than the loss of diversity of strategies because the future remains and will remain uncertain. Life itself has found its model, that of diversifying survival paths and risks to ensure its own long-term resilience. Portfolio managers did not invent the wheel.

The economy

Insurance companies, for instance, are a dominant sector in the world, representing a consolidated turnover of nearly 7,000 billion US dollars in 2021, which is considerable. (It constitutes 7% of the world GDP.) However, it is a fragile business by construction. The insurer collects premiums at the beginning of January and dreams of a world without any disruption, without any accident, so that it will not have to pay anything back during the year. However, if the environment were to change suddenly, like in the case of a major earthquake in Istanbul or Tokyo, many of these companies would go bankrupt. We know that this will happen one day. The last earthquake devastating Tokyo happened in 1900.

This seismic instability exhibits a frequency of 100 years, with an uncertainty of +/-100 years. In other words, the earthquake can happen now or in 100 years; and with the passing of time, the probability of its occurrence increases. Between two major earthquakes, insurers thrive and grow in size, like dinosaurs.

Another example is when governments imposed lockdowns during the pandemic – and work methods were disrupted and local businesses were severely affected – Amazon soared. Amazon is antifragile. When Western countries decided on sanctions against hundreds of Russian oligarchs, Dubai’s business soared. The famous “build it and they will come” model is antifragile.

Today, the world has turned unstable, witnessing the emergence of two opposing forces:

- Fragility: A conservative force, dominated by the United States, which seeks to return to the world of yesterday, to the former global order, which benefited many countries, with the United States in first place.

- Antifragility: Multiple forces, therefore non-dominant, that seek agility, in case the world of yesterday does not return.

Here, we point to Russia, China and Iran of course, but also those who are studying their geopolitical interests, like the Gulf countries, Turkey, India, Brazil, Africa, etc. Commercial trade between China and Russia has already jumped by 50% in one year.

We also point to developments in the Western world that were unimaginable a few months ago. Japan is considering resuming its civil nuclear activities. Germany, Italy, Poland and Hungary are now questioning the banishment of the combustion engine for cars in Europe by 2035, even though they voted it in June last year.

In this global instability, there are at least six rents at stake:

- The savings of developed countries

- Chinese bonds challenging the pre-eminence of US bonds

- The dollar “as safe as gold” or “as safe as oil”

- A decade of high energy price ahead

- A possible Asian economic boom

- The American military domination

The savings of developed countries

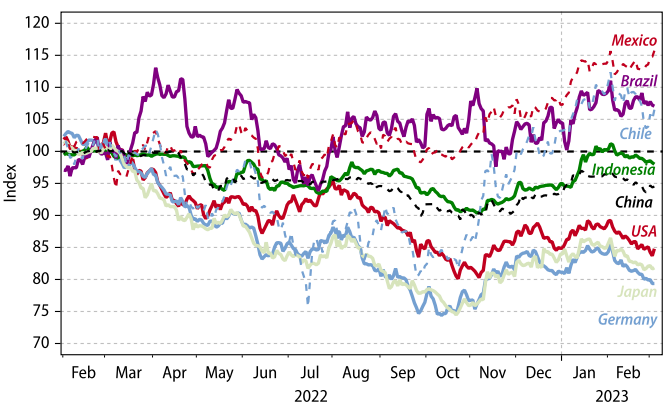

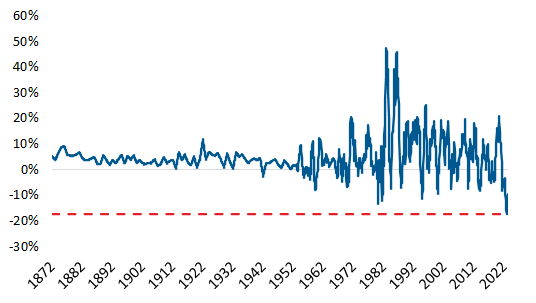

The drop in the value of a US 10-year bond over the course of a single year has reached the worst level in 150 years. The same is true for European and Japanese bonds. This is the first time in a period of liquidity contraction by major central banks that the most resilient bond markets are to be found in non-Western countries and not in the G7 countries.

Bond Market Performance Since Russia Invaded Ukraine

The bond market is the foundation of the remuneration of long-term savings. When pension funds in the United States, the United Kingdom and Northern Europe suffer heavy losses, the pensions of future retirees are at risk. This results in protest movements spreading to countries like Germany, which is known for its social stability.

The pain is nowhere near over. Inflation is now anchored in the Western world, as evidenced by the divergence between primary energy inflation flattening in the recent months and secondary inflation (inflation in non-energy products) showing no sign of relief. U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powel acknowledged on 7 March 2023 that U.S. inflation was not slowing as hoped and that he would continue to raise rates at any cost. The market is now anticipating terminal short rates above 5.5%, which does not bode well for bond holders.

If inflation in consumer goods does not fall back below the 2% target (which is a possible outcome and a way for governments to stabilise their debt to GDP ratio), the euthanasia of the Western rentier will continue.

Annual Returns on a 10-year U.S. Government Bond for the Past 150 years

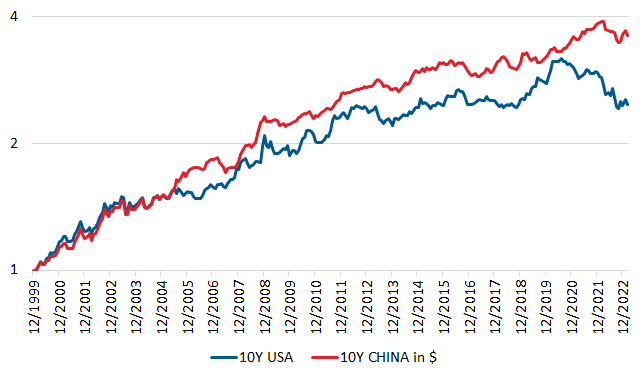

Chinese bonds challenge the pre-eminence of the US long bond as the risk-free asset of the world

Chinese bonds do not have good press in the West. In most French tenders we analyse for institutional investment mandates, two conditions are required: (1) that the investment be deemed compliant with the new environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards; and (2) that Asian investments do not contain exposure to China. These constraints are of a regulatory or political nature. They drain private savings towards projects deemed to be in line with the European geopolitical orientation.

The same is true in the United States, which is simultaneously expanding its trade deficit with China and exerting pressure to prevent Americans from investing in Chinese assets. Consuming Chinese goods – not letting US savings leak – is welcome.

The fact remains that a Chinese bond returned more than a U.S. bond for 5 years, 10 years or 20 years, both converted into the same currency. More worryingly for the United States, Chinese bonds have held up well during the bond rout in developed markets last year.

Thus, an investor from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Singapore, Brazil, South Africa or India would think that Chinese bonds are poised to compete with the U.S. global flagship market as the safest possible benchmark bond over the long term.

Comparative Performance of US and Chinese 10-year Bonds, in USD

The dollar “as safe as gold” or “as safe as oil”

The economic domination of the United States in the 20th century provided the dollar with a unique property – to be “as good as gold” – even after the end of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971, which abandoned the convertibility of the American fiat currency into gold.

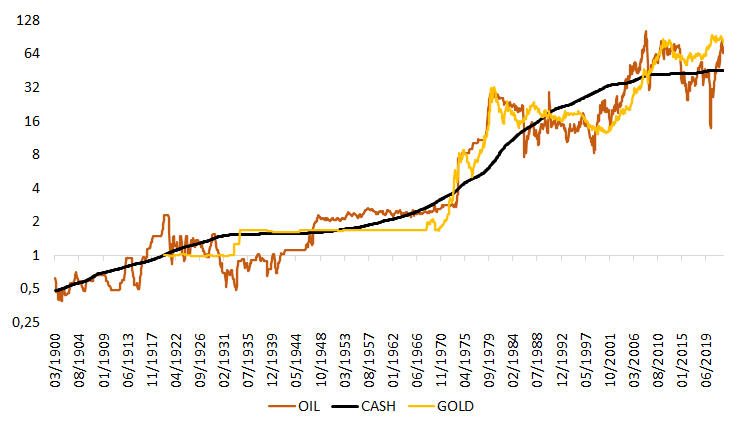

The following graph compares the value of a monetary deposit in US dollars, including interests, with the value of gold and oil since 1900. It shows that “as good as gold” can be extended to “as good as oil”. In other words, the international trade in primary energy and raw materials, denominated in US dollars, in effect created the fungibility of the dollar in oil. Holding dollars was the assurance of being able to buy primary energy, and thus the assurance of continuing to physically fuel a local economy even in times of economic or political upheaval.

The Value of a USD Deposit Capitalised Against the Price of Gold and Oil since 1900

The Russian-Ukrainian war and the Western sanctions against Russia change the situation. Countries like China or India had already signed energy import agreements with Russia that are not denominated in dollars. Even Saudi Arabia is raising this issue. The fungibility of the dollar in oil or gold is losing ground.

A decade of expensive energy ahead

The previous graph shows the existence of three forms of currencies following each other like dogs on a leash: The currency of today, let’s say the dollar; the currency of the past, gold; and the currency of the future, oil or energy in general.

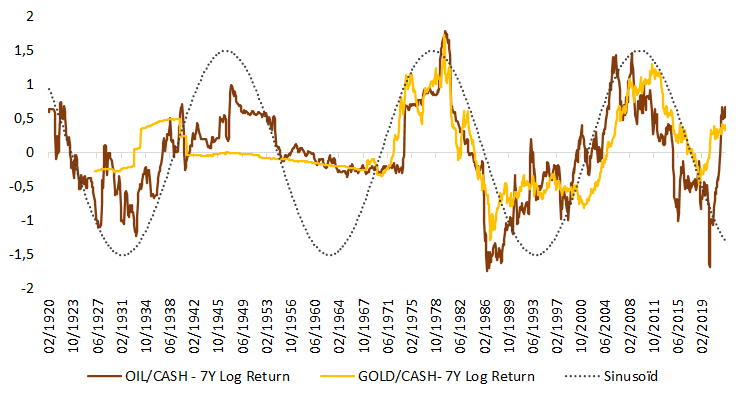

Physical currencies such as gold or oil oscillate around fiat money with a periodicity of about thirty years, as can be seen in the following graph displaying ratios between gold and oil on the one hand and fiat money on the other. When energy is cheap, the financial cycle turns very bullish since the economy is nothing but energy transformed. Conversely, stocks and bonds suffer in times of high energy prices.

The Russian-Ukrainian war has accelerated the cycle so that we have likely entered the bullish leg of the energy cycle, and therefore the bearish leg of financial assets.

Oil/Cash Deposit Ratio, Gold/Cash Deposit Ratio (7Y moving log returns i.e. measured by percentage) since 1920

A possible economic boom in Asia

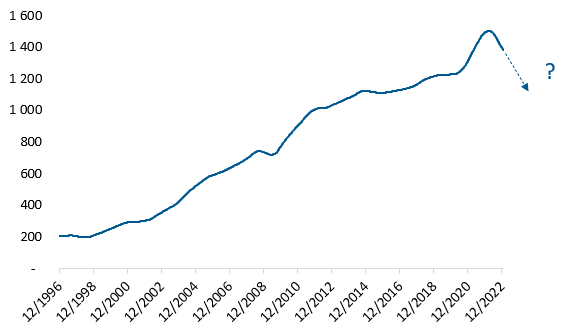

There may be some good news. Asian countries have learned a lesson from the crisis of the late 1990s. They did not want to see the International Monetary Fund dictate their economic and social policies ever again. The only solution was to maintain undervalued exchange rates in order to export more than they imported, work hard, consume little, and thus accumulate dollar reserves.

Evolution of foreign Exchange Reserves of Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea and the Philippines, in USD

Now that the Asian zone is likely to trade more and more in local currencies, with the support of the Chinese central bank stabilising cross currencies rates, these foreign exchange reserves in dollars become less and less relevant. They could be used, at least in part, to support local investment or intra-zone investments instead of funding the US budget deficit.

The US twin deficit has reached 8% of GDP and is expected to remain at that level until further notice. That’s a lot of dollars to find if former international investors turn their back to US bond offers. In contrast, a redirection of Asian savings towards domestic investments would greatly enhance economic growth in that region of the world.

Backed by currencies that did not monetize the Covid-19 crisis, the Asian zone could benefit from a triple merit scenario: strong currencies fighting world inflationary pressures, bond outperformance, and equity outperformance.

American military domination

The United States’ military domination has been the basis of the international order since 1945. This is also the reason why the war in Ukraine geopolitically goes beyond local borders. The United States “cannot lose the war” since a military defeat could jeopardise its imperial privilege, i.e. the fungibility of the US dollar in oil and the netting of its international deficits in its own currency.

Today, the military escalation is palpable, not only between NATO and Russia, but also between the United States and China. China intermediated a rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, is possibly preparing to supply weapons to Russia, and the Chinese Foreign Minister published an opinion piece entitled “American Hegemony and its Perils”. The US Air Force shot down Chinese spy balloons and threatened to send American marines to Taiwan.

The United States “cannot lose the war”, but neither can Russia or China.

Conclusion

The globalisation of the economy is a Ricardian process of optimisation that has a slow but detrimental side effect masked by the creation of shared value, namely the increase in the fragility of the economic system.

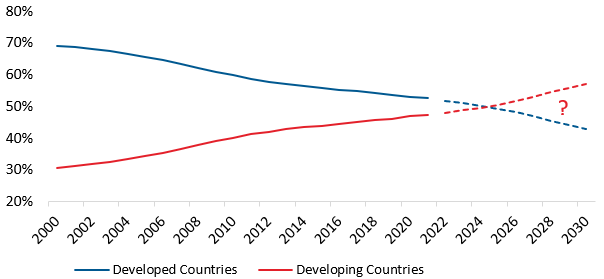

In 2000, the economic weight of developed countries represented 70% of world GDP, hence the little disputed global economic order led by the United States. However, in a little more than twenty years, everything has changed. Developed countries are losing their pre-eminence, especially since the internationalisation of the conflict is accelerating geopolitical rapprochement in non-Western countries. The war itself was only made possible by the gradual rebalancing of economic forces.

Share of World GDP of Developed and Developing Countries

After two decades of increasing fragility and a brutal evolution of environment, the economic and political world is looking for new ways to counteract fragility. We are living through a rare period where history is written from day to day.