The global currency market is facing digital disruption. Consumers around the world are flocking to cryptocurrencies, ushering in a more decentralized era in global finance. Governments are taking note and are rushing to develop central bank digital currencies (CBDCs)—digital forms of fiat currencies built on blockchain technologies. For now, the U.S. dollar remains king, but unless U.S. policymakers take decisive steps to adapt to an increasingly digital financial system, the United States risks losing the economic and geopolitical advantages afforded to it by the dollar’s dominance of the global financial system.

In responding to the growth of digital financial tools, the United States faces a classic “innovator’s dilemma” in which a dominant incumbent must respond to an insurgent innovator that threatens the incumbent’s position. The Biden administration is beginning to address this issue with the signing of a recent executive order directing U.S. government agencies to prioritize the development of policies to regulate digital assets and to examine the requirements and feasibility of launching a digital version of the dollar. But until a more comprehensive policy framework for digital assets is developed—a task likely to take years—U.S. policymakers must work to support the development of private-sector stablecoin alternatives to a Fed-issued digital dollar in order to adopt a more proactive mindset in countering challenges to the dollar’s dominance.

The innovator’s dilemma

The decision whether or not to launch a U.S. CBDC and build the infrastructure it requires bears all the hallmarks of the “innovator’s dilemma”—the business scholar Clayton Christensen’s framework for understanding the difficult choices facing incumbents responding to disruptive technologies.

Applying Christensen’s framework to Washington’s decision to launch a CBDC, the innovator’s dilemma facing U.S. policymakers can be described like this:

- A dominant incumbent (the U.S. dollar) garners the lion’s share of industry profits and benefits, but only incrementally innovates (e.g. SWIFT.gpi and FEDNow infrastructure upgrades) to meet customer needs.

- Meanwhile, insurgent innovators (e.g. digital currencies, stablecoins, decentralized payment networks) enter the market using new technologies (e.g. blockchain) and experience rapid adoption due to a superior value proposition (e.g. faster transactions, lower costs, privacy, flexibility, “bank by device”), but face a “chasm” before mass scale adoption.

- Larger industry players (e.g. central banks, China) adopt the same technologies both to protect their own business from these disruptors but also to gain market share from the dominant incumbent.

- Adoption by these large industry players and entrepreneurial fervor by the insurgents increases the disruption’s value to customers, making eventual mass scale adoption inevitable.

- The dominant incumbent now faces a hard choice: whether to adopt or fight against these disruptive technologies—and if adopting, how to do so effectively.

Alternatives to SWIFT and the U.S. dollar are coming from two directions: cryptocurrencies and central bank digital currencies. Cryptocurrencies (or “crypto”) are a form of payment that can circulate without the need for a central monetary authority such as a government or bank and are created using distributed ledger technologies and cryptographic techniques that enable people to buy, sell or trade them securely in a decentralized way. These decentralized networks are controlled by no one and enable privacy from government intrusion or intervention. Cryptocurrencies, including bitcoin, ethereum, and an increasing number of alternatives, have risen in value to ~3% of the global money supply.

CBDCs use much of the same underlying technology as cryptocurrencies, but rather than de-centralizing control of money and enabling secrecy, they centralize the infrastructure of a digital currency, enabling greater control and inspection. A CBDC is an alternative form of fiat currency as an electronic record or digital token of a country’s official currency. As such, it is issued and regulated by the state’s monetary authority or central bank. CBDCs are backed by the full faith and credit of the issuing government. Ninety countries (representing more than 90% of global GDP) are exploring a CBDC, while nine countries have fully launched such a currency. However, all of those countries that have launched a CBDC are small with limited currency float.

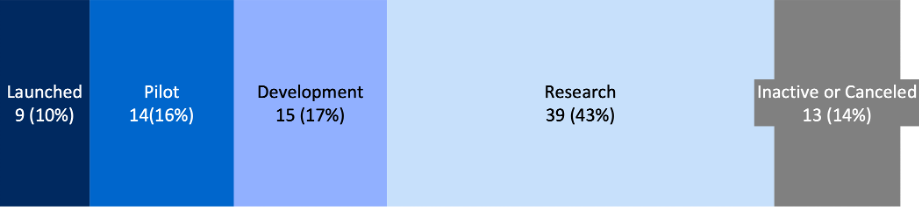

Figure 1: Current Status of the 90 Countries Evaluating or Piloting CBDCs

Source: The Atlantic Council’s Central Bank Digital Currency Tracker

CBDC “hubs” represent the next step in making digital currencies effective for international payments. These hubs can enable clearing and settlement capabilities between bilateral trade pairs. Currently, CBDC implementations are deployed on various blockchain and other IT systems which currently do not talk to each other. Enabling clearing and settlement of digital currencies requires solving technical interoperability challenges as CBDCs and stablecoin networks are being implemented on a variety of blockchain or other IT systems that do not currently talk to each other. Scaling digital currencies across borders requires countries to coordinate on these type of interoperability issues as well as address complex cross-jurisdictional regulatory hurdles. While this is difficult to do, there are many efforts underway to make it happen. Switzerland, Hong Kong, Singapore, and many others localities are attempting to build the regulatory frameworks for creating the digital currency exchanges that represent the critical hubs for the future international monetary system.

CBDCs can solve some of the inefficiencies of the dollar-dominated financial system. Global corporations pay an estimated $120 billion in transaction fees every year, and CBDCs can lower these costs. CBDCs can promote financial inclusion, meaning those who are unbanked can get easier and safer access to money on their devices. They can compete with private companies that need incentives to meet transparency standards and limit illicit activity. They can help monetary policy flow more quickly and seamlessly. They can help fine tune and calibrate capital controls.

For now, the U.S. dollar remains the king of global finance. The dollar is the global reserve currency, representing 60% of global reserves. The dollar represents one pair in 88% of global currency trades, 60% of international banking liabilities, and is listed on 79% of international trade invoices. More than 65 countries peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar. The SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications)-based payments system is used for more than 50% of global cross-border transactions. While SWIFT can process currencies other than the U.S. dollar, it is controlled by the central banks of ten countries allied with the United States.

The primacy of the U.S. dollar grants the U.S. government and economy special privileges, including the ability to print money with relative freedom, issue debt at low interest rates reducing the cost of capital both for the government and U.S. firms, maintain long-term and persistent trade surpluses. In addition, the SWIFT system’s compliance services (“know your customer” rules and anti-money laundering measures) enable the U.S. government to monitor global transactions—and therefore apply economic sanctions to countries and individuals, a privilege afforded to no other governments at the same scale. As the adoption of cryptocurrencies and CBDCs increases, the benefits afforded the United States by the dollar’s dominance will gradually decrease.

‘Stuck at the chasm’: CBDCs still not mainstream

Despite their promise, countries, businesses, and consumers have not yet adopted digital currencies at scale. None of the top seven reserve currencies that represent more than 95% of global reserve currencies have yet launched a digital version. Indeed, it would be a step too far to say that America’s global trading partners want to replace the dollar; for these countries, the dominance and enormous liquidity of the dollar has both benefits and costs.

There are challenges to mass adoption of digital currencies. To play an effective role as stores of value and medium of exchanges, currencies need to have the trust of their holders and users. Volatility, cyber-theft, and the usage of private digital currencies for illegal activities currently limit trust and adoption. Building effective cross-border payment systems requires collective action between both state and commercial actors, on standards, underlying technologies, and regulation. Finally, big companies that drive the business-to-business transactions that underpin cross-border payments abhor complexity, so any system of digital currencies and multi-currency hubs must be simpler to use and pose less risk than the current dollar-based system.

Many of the barriers to digital currency adoption would be best removed by the active involvement of the United States and a digital dollar. But U.S. entry into the emerging global digital currency ecosystem would also accelerate the very trends that threaten to disrupt the U.S. dominance of the international monetary system.

A big player goes digital: China’s e-CNY

After more than 8 years of planning, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) is set to launch the digital renminbi (e-CNY) in the coming year. China’s e-CNY is currently the most advanced effort globally to scale the commercialization of a CBDC via large-scale pilots and deployments. This includes widespread tests regarding e-CNY functional capabilities, online e-commerce usage, ATMs, point-of-sale terminals, hardware smart cards (allowing financial inclusion of citizens without smartphones), biometric identification, stimulus and subsidy dissemination, and even cross-border activity connecting mainland China to Hong Kong and Macau. More than 261 million digital wallets have been opened with more than $13.9B in total transactions completed with scaled use cases and pilots across the country.

China’s position as a trading powerhouse could position the e-CNY to spur the adoption of digital payments. China controls 14% of global exports (nearly twice that of the United States), and many U.S. trading partners now trade more with China than with the United States. (Nonetheless, the RMB only represents 2% of global payments.) The Chinese population are already pioneers in using digital payments, and the country has more than 850 million online payment users. Alipay and WePay are the largest mobile consumer payment systems in the world. These datapoints are indicative of the opportunities Beijing sees in launching a digital renminbi, which will be the first top 10 reserve currency to pilot digital currency at scale.

But China’s push for the e-CNY may not immediately disrupt the existing international monetary system. China’s central bank has indicated that the primary focus of the e-CNY will be on the domestic mainland market. As such, the adoption of the e-CNY may blunt the domestic and global success of WeChat and Alipay, which are the world’s most widely used consumer payment tools. There is increasing evidence that Chinese government policy is intended to preference a government-backed payment standard rather than letting WeChat and AliPay utilize their proprietary architectures. This reflects the ongoing governance challenges China faces in its technology policy—the desire to align Chinese private companies to government policy mandates can limit the very success of those companies to compete outside of China. Many factors beyond ease of digital transactions drive the choice of reserve currency, including currency convertibility, depth of capital markets, and more. These factors, especially the Chinese government’s capital controls, will limit the potential adoption of the RMB as a global reserve currency, despite the e-CNY’s potential to drive international adoption.

Nonetheless, the platform provided by the e-CNY creates an enormous sandbox for Chinese companies and entrepreneurs to innovate new services and opportunities (if the Chinese government enables them). These experiments and innovations may create a blueprint for new application adoptions in other regions (e.g. the eurozone) that do not have the inherent drawbacks of the RMB nor the closed PRC capital account. In this way, the e-CNY could spur adoption of digital currencies outside the RMB ecosystem.

Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine and the coordinated global response to it may spur greater interest in the development and adoption of digital currencies. In response to Russia’s invasion, the United States and its allies have imposed massive financial penalties on Russia, including freezing its central bank from global financial markets and banning seven Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system. These sanctions have essentially cut Russia off from the international monetary system. Other nations may view the ability of the United States and its allies to impose these types of sanctions as unsettling and invest in alternatives to the existing dollar-dominated, U.S.-controlled financial system. The result may be a loss of confidence in SWIFT and traditional financial ecosystems, accelerating the pivot to emerging digital currencies.

The U.S. government incumbent response to date: incremental improvements

The U.S. government, led by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department, initially adopted a wait-and-see approach to launching a digital dollar. The Federal Reserve’s first published paper on the subject, released earlier this year, did not take a concrete position on launching a digital currency and recommended additional investigation. The recent White House executive order on cryptocurrencies did not define a concrete strategy; rather, it instructed federal agencies to examine the risks and benefits of digital currencies for consumer protection, financial stability, illicit activity, U.S. competitiveness, financial inclusion, and innovation.

Separately, the Federal Reserve is making incremental innovations to the existing financial system. Swift.gpi and the FedNOW messaging system (intended to enable instantaneous transfers) make the existing payment networks operate more efficiently, but these are still centralized systems which require those who use them to join a U.S.-controlled architecture.

A path forward addressing disruption and innovation

In considering a realistic U.S. policy response to CBDCs, policymakers can take two steps.

First, U.S. policy efforts should reduce the attrition to emerging digital currency alternatives in the short-term by reducing the costs of foreign exchange transactions and providing alternatives for the under-banked. This would reduce market demand for the digital currency and digital trading hubs put forth by other nations. Actions on this front would include accelerating SWIFT.gpi technical improvements and reducing the cost of SWIFT transactions. More importantly, providing a regulatory framework that enables U.S. dollar-denominated stablecoins to be used in foreign trading transactions would fill the market gap before the United States builds out its own CBDC.

Second, the United States should recognize that simply improving the existing system is not good enough and consider an aggressive approach taken from the high-tech “innovators playbook.” To put it simply: Be aggressive, be proactive, and do not wait for someone to disrupt your business—disrupt yourself.

How could the United States do this?

- Continue to develop coordinated national policy around digital currencies and accelerate the development of the digital dollar, learning from the pilot activities of others. The United States should adopt the philosophy of being a “fast follower.”

- Take the lead on global standards for digital currency transactions and regulation. This should include forming a U.S.-led global standards body to set the rules and interconnectivity protocols for dollar-denominated transactions. This would place U.S. policymakers in an influential position to write the rules for the digital-currency monetary system of the future.

- Build out frameworks for digital currency privacy, compliance, and governance that reflect U.S. values, allowing such frameworks to proliferate globally.

- Establish efforts to develop digital currency trading hubs in the United States. The U.S. government should partner with leading technology companies to build a multi-currency trading hub with an architecture that is controlled by the United States and trusted allies but can be linked to other trading hubs.

- Join in the development efforts of other leading digital currency hubs, both to influence them to support U.S. objectives and to learn best practices.

- Create an enlightened regulatory sandbox to support the development of the stablecoin market and pilot regulations driven by market-participant feedback.

- Create an industry consortium in the United States to build out digital payments infrastructure from common standards to adoption incentives. This might involve a public-private partnership to drive adoption.

- Build digital currency issues into foreign-policy engagement with key allies, especially in Asia and Africa—the key battlegrounds for digital currency dominance between the e-CNY and its competitors. Sustaining digital currency infrastructure centered on the U.S. dollar should be a critical component of U.S. engagement and a means to align our goals with those of our trading partners.

- Ensure that the efforts described here leverage the power of the dollar’s liquidity to keep transaction costs low. This can be accomplished by incentivizing major financial institutions and market makers to adopt stablecoins linked to the dollar or a future digital dollar.

U.S. government policy requires a delicate balance between market- and efficiency-focused objectives on the one hand and national-security and foreign-policy objectives on the other. Achieving that balance requires simplifying payments, reducing cross-border transaction fees, and serving the under-banked, while also maintaining the ability to monitor global payment flows, controlling access to digital currency exchange platforms for the digital dollar, and enabling sanctions against rogue actors. Unless the United States shows up on the global playing field now and takes a leadership role to determine how these trade-offs will be made, other countries will be the ones writing the rules.

As the United States works to catch up in adopting digital currencies, even a flawless strategy executed with great competence might still lead to a world in which America loses some, if not much, of its leverage over the existing global financial system. However, a sluggish, reactive U.S. strategy will ensure such an outcome. Digital currencies will render obsolete many existing standards and rules of the international monetary system. The emerging international monetary ecosystem will be populated with digital currencies from countries around the world, not just the e-CNY. Countries will be able to directly exchange digital currencies in a bilateral way and without going through SWIFT or similar settlement systems. When the technology allows seamless and instantaneous convertibility from one sovereign currency into another, it changes the practical need for a dominant global reserve currency.

The U.S. government needs to rapidly position digital payment and finance options that serves the needs of the United States, its financial system, its allies, and its global trade partners. The U.S. should do so from its position as a dominant economic power and lead the adoption of digital currencies based on the dollar. How to do so is not just a one-off decision about whether to authorize a digital dollar or not; rather, it is a long journey that requires building a global ecosystem.

Michael Sung is a technology investor and the chairman of CarbonBlue Innovations.

Christopher A. Thomas is a nonresident senior fellow in Foreign Policy at Brookings, the chairman of Integrated Insights, a board director at Velodyne LIDAR, and a visiting professor at Tsinghua University.