Introduction

China no longer seeks a global yuan due to the actions of state-owned companies and Chinese individuals moving money abroad. In 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was organized to expel US dollars from the Chinese economy and limit the need for market interventions. However, Chinese state-owned companies initiated a speculative attack that forced the hand of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). Chinese authorities propped up capital markets, restricting households that sought to move capital overseas. Meanwhile, the United States has increasingly weaponized the global greenback, and the increasing threat of US sanctions has limited the options of Chinese policymakers.

Central to the yuan’s future is whether China will attempt to de-dollarize the global economy or merely hedge against potential US sanctions. China is constrained to the latter for the next few years. Attempting to de-dollarize would require China to maintain free capital markets. However, lessons from 2015 suggest that doing so would risk another financial crisis in China. Still, China should continue to build central bank agreements for cross-border trade settlements in Renminbi to counteract the US dollar’s sanctioning power.

Strict Capital Controls Post-2008

In 2008, China maintained an undervalued peg to the US dollar; the Chinese government artificially devalued the yuan to induce higher exports. As the economy recovered from the Great Recession in 2009 and 2010, the PBOC allowed the Renminbi to appreciate as a “crawling peg” (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Chinese Yuan Renminbi to US Dollar Spot Exchange Rate, annually.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

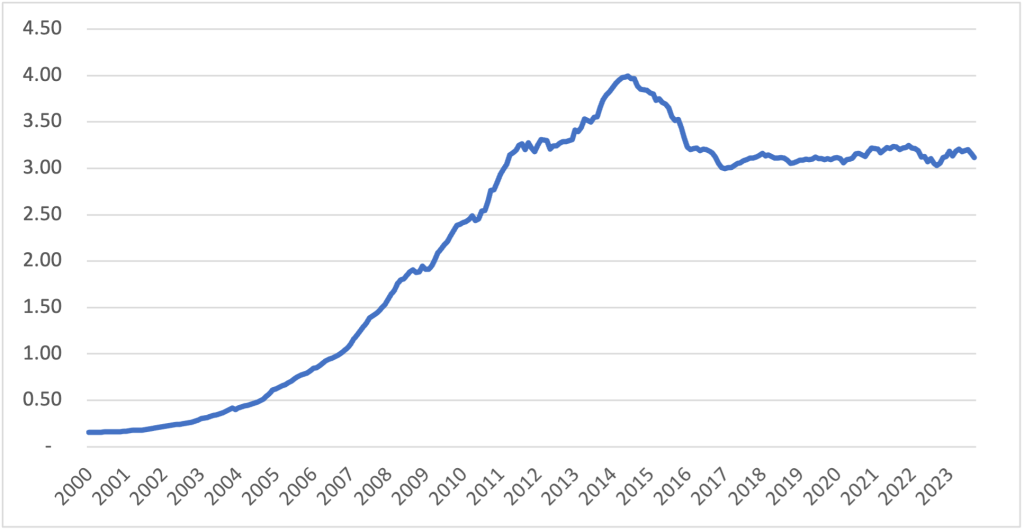

The Chinese currency remained undervalued relative to true market value, its “shadow price,” as the PBOC made massive purchases of foreign currencies, mainly US dollars. Chinese foreign reserves climbed inexorably until the country had accumulated almost USD 4 trillion in June 2014 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – China Foreign Exchange Reserves (USD trillion)

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Globalized Yuan Aspirations

For the first five years after the great financial crisis, Chinese foreign reserves doubled from USD 2 trillion to 4 trillion. But starting in 2013, the Chinese government generated considerable demand for the yuan by launching the Belt and Road Initiative while quickly selling US dollars. With loans totaling over USD 120 billion, the BRI-backed projects ranged from highways to power plants. From 2000 to 2013, net capital inflows to China averaged USD 800 billion annually and remained at similarly high levels in subsequent years (Figure 2). The Chinese government sought to internationalize the yuan, culminating with the Chinese currency’s inclusion in the Special Drawing Rights (SDR), the IMF’s international reserve asset.[1] China, flush with foreign investment, hoped the yuan would replace the US dollar as the global reserve currency.

Governments are typically faced with a trilemma. They can choose at most two of three policies: monetary policy autonomy, fixed exchange rates, and free capital flows. The United States, Japan, Brazil, and India, among others, maintain monetary policy autonomy and free capital flows but lack a fixed exchange rate regime. Eurozone countries abandoned monetary autonomy (outsourced to the European Central Bank) to create a euro-to-euro peg between their countries and allow money to flow between these economies unimpeded. Historically, China has opted for monetary policy autonomy and a fixed exchange rate with the US dollar (and, later, with several currencies). According to the trilemma, capital should not move freely in and out of the country—that was the reality for Chinese consumers and companies throughout the 2000s due to the country’s strict capital controls.

Pre-2013 trends fueled Chinese global currency aspirations. With demand for the yuan growing rapidly, Chinese authorities pursued yuan internationalization and more free capital markets, ignoring the trilemma. China believed that seemingly infinite reserves would preclude speculative attacks that commonly cause the downfall of governments that try to maintain fixed exchange rate regimes, monetary policy autonomy, and open capital accounts. Authorities thought it impossible that enough capital would leave the Chinese economy to deplete its reserves.

Economic Crisis and China’s Response

However, in early 2015, the Federal Reserve raised US interest rates for the first time since 2008. Simultaneously, expectations for the Chinese economy turned. A consensus formed that the Chinese economy would suffer a hard landing. Thus, the yuan became overvalued relative to its shadow price. Capital started flowing out of China rapidly, leading to a speculative attack on the currency as investors sold yuan assets. In 2016, households sought to transfer as much money as possible when their limits for sending US dollars to foreign accounts reset. Almost USD 1 trillion left the Chinese economy in 2016. With restrictions on capital outflows lifted and ample credit from local banks, state-owned companies purchased global businesses in deals totaling USD 200 billion. Chinese 2016 outbound mergers and acquisitions (M&A) reached almost four times as large as the previous year (Figure 3). Chinese companies were effectively betting on the yuan’s devaluation by buying foreign businesses. Thus, a speculative attack marred authorities’s intentions of a global Renminbi.

Figure 3 – Outbound M&A deal value by companies from China between 2015 and 2022 (in billions USD)

Source: PWC, 2023.

Source: PWC, 2023.

In August 2016, the PBOC took action against the speculative attack. It allowed the yuan to devalue by over 3 percent daily for two consecutive days but tightened capital controls. In September, the government introduced a 100,000 yuan annual limit on cash withdrawals from foreign ATMs and restricted underground transfers. But most critically, the PBOC tightened capital controls for private and public companies. This caused the value of outbound M&A to fall by 90 percent from 2016 to 2023, as Chinese companies had limited access to debt to finance the acquisition of Western firms.

Nevertheless, Chinese authorities did not simply return to a currency system with a non-volatile exchange rate, tight capital controls, and monetary autonomy. Today, the yuan is much closer to a free-floating currency. Before 2016, the yuan fluctuated little, but it now varies according to the business cycle. For instance, the Chinese currency devalued at the beginning of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, appreciated when restrictions in the country eased, and devalued again as Western central banks lifted interest rates (Figure 1). Since the speculative attack in 2016, China’s foreign reserves have remained almost constant at USD 3 trillion (Figure 2). Instead of intervening to keep the yuan under certain thresholds, the PBOC has allowed it to appreciate and depreciate according to the relative amounts of foreign currency entering or leaving China.

After the speculative attack of 2015, the Chinese government changed its currency system, adopting a dirty floating exchange rate system, not the strict peg of the early 2000s. Despite China’s claims that it wants to de-dollarize, the PBOC is unlikely to entirely abandon capital controls. The fear of currency volatility destabilizing the Chinese economy will likely trump the desire of Chinese policymakers to make the yuan a global currency. The speculative attack from individual agents, consumers, and companies ended hopes of a genuine Renminbi standard. It also required Chinese authorities to fundamentally change the BRI. Since 2017, annual BRI disbursements have declined substantially and are now almost exclusively lightly subsidized loans for Chinese companies to build infrastructure in foreign countries. De-dollarization is still a goal, but authorities are handcuffed by their preference for capital controls.

Chinese entities will continue to have to cope with restricted access to foreign currency. Capital controls make local financial markets more resilient to crises but less efficient. Capital controls restrict foreign companies’ routine business operations, such as receiving payments from Chinese customers as well as paying dividends and royalties to Chinese stakeholders. More informed investors will continue to pursue the few avenues for sending money abroad, such as through the Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor (QDII) program. All the energy spent procuring ways to send money abroad saps Chinese productivity.

China’s Strategy Moving Forward

In the past, Chinese authorities believed a global alternative to the dollar system was possible. However, today, China focuses almost exclusively on promoting the yuan through trade. Instead of being paid in US dollars, exporters are paid in their local currency with trade being settled when Chinese importers buy local products. Thus, an Argentinian exporter may be paid in pesos, while a Chinese exporter to Argentina is paid in yuan, bypassing US dollars. Yet, without a commitment to free capital flows, China cannot pursue de-dollarization moving forward. Authorities must take a wait-and-see approach unless economic priorities change.

Presently, de-dollarization is, in essence, a risk management measure for China. The United States can sanction institutions by limiting their ability to access international payments in US dollars, an option no other country shares. (Only Europe and the United Kingdom come close with their abilities to limit transactions in pounds and euros). China’s current stance limits the potential damage to the Chinese economy from possible US sanctions. However, they do not match past de-dollarization goals. Due to the risk posed by potential US sanctions, Chinese authorities should continue to devise measures to limit the dollar’s potential as a weapon if the economic conflict with the United States intensifies. Still, China cannot allow capital to flow entirely freely into its economy without risking another domestic currency crisis.

…

Rodrigo Zeidan is a Professor of Practice of Business and Finance at NYU Shanghai and an Affiliate Professor at Fundacao Dom Cabral. Professor Zeidan is the author of Economics of Global Business (MIT Press), The General Model of Working Capital Management (Palgrave Macmillan), and five other books. His research has also been published in some of the top journals in finance and economics, such as the Journal of Corporate Finance, Nature Sustainability, Energy Economics, Harvard Business Review, International Journal of Production Economics, and Journal of Business Ethics. His recent research focuses on Sustainable Finance alongside Corporate Finance and Industrial Economics issues. Rodrigo has a biweekly column at Folha de S. Paulo, the largest Brazilian newspaper. He has written extensively for international media outlets, including the New York New Times, CNN, the World Economic Forum, Bloomberg, and Americas Quarterly. Rodrigo is also Associate Editor of the Journal of Economic Surveys, Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, and the Brazilian Review of Finance. He holds a position as a Senior Scholar at the Center for Sustainable Business, NYU Stern.

[1] The SDR is not a currency, but its value is based on a basket of five currencies—the US dollar, the euro, the Chinese Renminbi, the Japanese yen, and the British pound sterling.

Image credit: Eric Prouzet via Unsplash.