Enrico Grazzini

Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize winner for economics, has recently written an article titled “Can the euro be saved?”. He wrote:

The euro may be approaching another crisis. Italy, the eurozone’s third largest economy, has chosen what can at best be described as a Eurosceptic government. This should surprise no one. The backlash in Italy is another predictable (and predicted) episode in the long saga of a poorly designed currency arrangement”. Then he proposes a dual currency system for Italy: “Italy is large enough, with enough good and creative economists, to manage a de facto departure – establishing in effect a flexible dual currency that could help restore prosperity.

Stiglitz makes it clear that a double currency regime could boost aggregate demand and revitalize the Italian economy. But he adds:

This [dual currency system] would violate euro rules, but the burden of a de jure departure, with all of its consequences, would be shifted to Brussels and Frankfurt, with Italy counting on EU paralysis to prevent the final break. Whatever the outcome, the eurozone will be left in tatters.

My aim here is to demonstrate that the dual currency system does not necessarily lead to the breaking of the euro and to ‘Italexit’.

A country like Italy could autonomously decide to introduce some money complementary to the euro without infringing any of the eurozone rules.

Moreover, if the European Central Bank wanted to “save the euro”, expand the European economy and strengthen the European common currency against the other world’s reserve currencies, it should promote in the whole eurozone a double currency regime, based on the euro and Tax Discount Bonds as a national quasi-money issued by the state. TDBs are financial instruments immediately convertible into euro: they could soon increase aggregate demand and the real economy in every single country of the Eurozone without raising their public debt (see below). Moreover, they could get a good rating from the agencies: so they would be accepted as good collateral from the ECB and also welcomed by banks and financial operators.

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

Austerity is counterproductive: we need an alternative way

To solve the Italian debt problem (€2.3 trillion or 133 per cent of GDP), the EU, mainstream academics and conservative politicians always suggest, as a litany, cutting public spending and the cost of labour, but unfortunately Italian GDP has been hit via such measures in the past.

There is another solution the ECB should consider very carefully.

The European Monetary Union appears to be a system too rigid, like a cage, for 19 very different countries in terms of productivity, inflation, trade balance and technological progress.

Moreover, under its statutes, the ECB cannot save a country plunged into a deep and lasting crisis. Indeed, EMU governance has three fundamental flaws: the rule of no restrictions on the free movement of capital; the rule of non-monetization of public deficits; the rule of no bail-out. They mean every country in the eurozone is potentially subject to speculative attacks on volatile financial markets, and, in the event of a major financial crisis, the ECB cannot intervene to save even the euro. The euro is thereby always prone to crisis and not irreversible as Draghi claims.

To protect the euro, any eurozone member must have the right to issue its own complementary quasi-currency in order to undertake counter-cyclical actions and avert the crisis. To implement an effective and flexible monetary policy, eurozone states must regain some form of sovereignty in this field. Of course, this new national system should be law-abiding and respectful of the eurozone rules. It must not go against the ECB monopoly on currency issuance as the European legal tender; moreover, the new national quasi-money must comply with the eurozone fiscal constraints on public debt and public deficit. The complementary money should not be a parallel currency; on the contrary, it should be accepted not only by the ECB but also by the banking system.

The euro and Tax Discount Bonds could and should coexist

Suppose that a periphery member state of the eurozone, although burdened by heavy public debt, aims to implement an expansive policy but wants to respect the eurozone budget constraints and not increase its deficit at the same time.

The government in question – e.g. Italy’s – could decide to issue billions of euros via a new financial instrument, the TDB.

TDBs entitle their holders to reduce their tax payments three years after their issuance. In the fourth year the TDBs can be used at their nominal value to reduce taxes and other obligations to the state (contributions, tariffs, fines, etc.).

The bonds, however, just like all other government bonds, such as bunds or gilts, can be sold immediately on the financial market in exchange for legal money, for euros, and can therefore immediately increase spending power in the economy.

Being short/medium-term securities guaranteed by the state to “pay” taxes, TDBs would be traded on the financial market at a minimum discount rate. In fact, they be usefully employed to “pay” taxes even if the state defaults: so the TDBs will certainly be worth more than a ten-year debt bond. In practice, 100 euros of TDBs will be equivalent to 100 euros, or slightly less.

Thanks to this conversion, in the real economy will circulate the euro and not some strange kind of parallel money (as would be the mini-bills paper money proposed by the Lega, which would become an alternative payment system prohibited by Maastricht).

The true novelty is that TDBs will be assigned free of charge and debt-free to: a) public institutions to implement a New Deal program aimed at increasing employment, building up new infrastructures, reinvigorating public welfare; b) to families (especially low-income ones) to increase their purchasing power; and c) to companies to cut their labour costs, improve their competitiveness and thus prevent any domestic demand expansion from exasperating the balance of payments problem. As a matter of fact, the TDB assignment to the firms should be compared to a currency devaluation.

The other very important advantage is that the bonds will not generate debt neither at the time of their issuing nor when they will mature.

In fact, at the time of issue, the state does not outlay any money. The TDBs cannot even be accounted for as debt because the government commits itself not to repay them in euros but only to grant tax relief on future taxes; but, according to accounting principles, tax reductions are never computable as a debt.

When the TDBs will be used to pay taxes, after three years from their creation, the tax deficit that would be produced all things being equal, will be offset by the growth of GDP thanks to the multiplier and inflation effect.

Tax Discount Bonds increase GDP without increasing debt, and pay for themselves

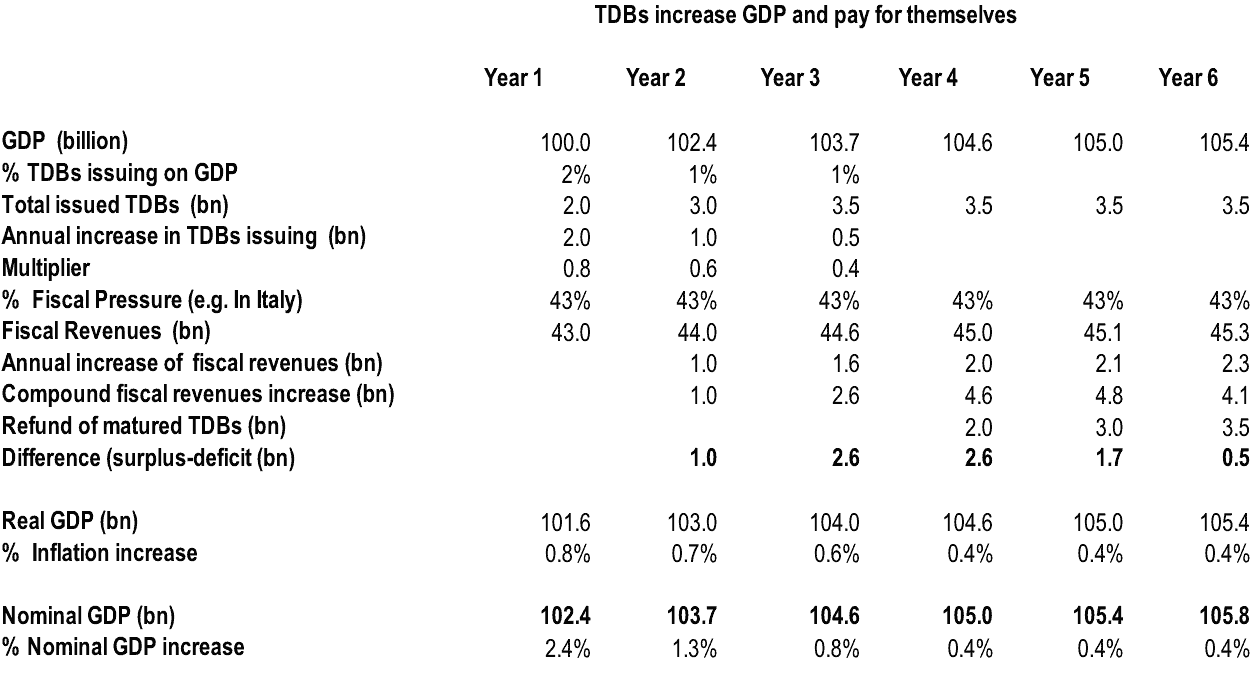

TDBs emissions could start at a level of around 2% of GDP – about € 35 billion for Italy -: the new demand would initially increase GDP by around 2-3%, then the TDBs issuing will be fine-tuned until full recovery from the “output gap” produced by the crisis. In the period from the issue of the TDBs to their maturing, the income multiplier will enter to effect and every newly issued euro will generate a strong increase in real GDP. Moreover, nominal GDP will go up because of demand growth and consequent inflation. When the TDBs mature, the nominal GDP growth induced by inflation and the multiplier effect will increase tax revenues in such quantity that these will offset the initial cost of the TDBs. Eventually, issuing TDBs will produce fiscal surpluses. The estimates shown below on the two key variables – income multiplier and inflation – in this simplified model appear to be very conservative, but also realistic and plausible. The table clearly indicates that issuing TDBs can increase GDP significantly, generate a surplus, and ultimately pays for itself.

The ECB should accept TDBs as collateral

If the TDBs have – as they certainly will – a good rating, according to its own rules, the ECB will automatically accept them as collateral for granting loans to the commercial banks. So even the banks will be very happy to accept these new free-risk government securities; and the support of the ECB and the banking system is absolutely necessary to introduce a viable and successful dual currency system across the euro area. The dual monetary system could be decisive for helping the ECB to make the euro really irreversible.

The other very important outcome is that financial markets – if they acted rationally – would happily accept the TDBs issued by governments, by seeing that these measures increase GDP and decrease the debt to GDP ratio from Year 1 (see table above). In fact, thanks to the double currency system, the financial operators would be sure to get back their entire loans.

The EU Commission could not object because the TDBs are not parallel money and do not generate public debt, but surplus.

So, contrary to Stiglitz, thanks to the TDBs issuance, Italy and the other countries of the eurozone periphery will not be forced to exit the Eurozone in order to expand the economy. The adoption of TDBs at national level is possible without modifying the European Treaties and rules.

Enrico Grazzini is a business journalist, essayist on economics and business strategy consultant. For more than 30 years he has worked for many Italian newspapers and magazines such as such as Corriere della Sera, MicroMega, Il Fatto Quotidiano, Economiaepolitica.