ECONOMYNEXT – Sri Lanka has been on a drive to expand government by abandoning cost cutting, based on a cookie-cutter model peddled by the International Monetary Fund to a number of other countries for several years.

But high taxation is not a substitute for monetary stability.

There is no dispute that removing exemptions is necessary as it is a denial of equal treatment under the law, if nothing else, but all these efforts will come to nought without sound money.

Now that there is a default and a crisis, taxes have to be paid to maintain a large 20-pct of GDP government and reach debt sustainability, but that is not the way to bring prosperity to the ordinary people in the long term.

Neither is tipping people into poverty with currency depreciation and giving them a social safety net. Sound money is the ultimate social safety net and will reduce the need for subsidies. Indeed, in the stable exchange rate East Asia, the clamour for subsidies and their use to win elections is absent.

If monetary stability is denied to the people through flexible exchange rates or flexible inflation targeting and their cousins, the fallout in terms of currency crises and economic slowdowns, deal devastating blows to the fiscal framework itself which no amount of taxation can fix, as clearly shown in Latin America and in Sri Lanka in recent years.

IMF policy and Washington consensus is not Thatcherite

It is essential to clear some misconceptions or ‘narratives’ that are spread by talking heads in Western media.

People are told time and again that IMF’s reform based programs which started in the 1980 to fix defaulting Latin American soft-pegs which collapsed repeatedly – sometimes called the Washington consensus – were based on Reagan and Thatcher style reforms.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

The IMF programs which were originally peddled to Latin America and by extension to Sri Lanka, lacked the basic ingredient of sound money that was the bulwark of the Thatcher program of reform and stability. In fact, Thatcher took over from two back-to-back IMF programs.

IMF effectively or may be unknowingly, eggs on currency collapses by empowering reserve collecting central banks to do aggressive floating rate style monetary policy through ‘central bank independence’ and then claims the currencies are ‘overvalued’.

One reason for debasing money is the vain hope that some magic export competitiveness will come from debased unsound money. But the resulting trade controls, social unrest and political instability, keep foreign capital out and triggers flight or domestic capital.

Depreciation is the standard Mercantilist dogma that drove social unrest in the third world and also disrupted developed nations in the 1930s but was rejected by Germany, Japan and the most successful East Asian export powerhouses after World War II.

The IMF programs are far from the Margaret Thatcher/Geoffrey Howe/Alan Walters style policy, which was intellectually backed by Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, among others.

The basis of Thatcher reforms was sound money. Howe’s budget and monetary policy, came after IMF programs in the ‘Great Inflation’ period, failed to stabilize or put the UK on a growth path, or remove exchange controls.

The UK had 11 IMF programs when it ran Sri Lanka style contradictory monetary and exchange rate policy, with Keynesiansim and output gap targeting, though not all were drawn down.

Sound Money

This is what Geoffrey Howe said.

“It is crucially important to re-establish sound money. We intend to achieve this through firm monetary discipline and fiscal policies consistent with that, including strict control over public expenditure.”

Present day economists and IMF have little or no idea of what sound money is.

Pushing aggressive monetary policy based on the in-vogue anchor conflicting monetary regime – money supply targeting conflicting with reserve collections then and domestic inflation targeting conflicting with the balance of payments now – does not solve anything.

It failed in Latin America and it failed in Sri Lanka from 2012 to 2019 and then up to 2022 taxes were also cut Barber boom style in fully fledged macro-economic policy. Thatcher also served in the Barber boom administration and seems to have learned well.

The fiscal probity of the Thatcher/Howe program was to reduce the deficit and reduce the size of the government. Not to expand the state as a share of GDP through taxation, allow spending to catch up and leave the deficit unchanged, as happened from 2015 by abandoning spending based consolidation.

In Sri Lanka spending went up from 17 to 20 percent of GDP under revenue based fiscal consolidation under the previous IMF program as spending-based consolidation was abandoned and monetary instability from flexible inflation targeting triggered currency crises and reduced growth.

The repeated Western statist dogma is that 20 percent spending to GDP is not a problem for a developing country.

But people in this country know how the state was expanded with unemployed graduates and spending is bloated with high nominal interest rates coming from high inflating unsound money.

In Sri Lanka IMF’s driven income tax rates also led to a backlash from some professionals, who helped bring Gotabaya Rajapaksa to power along with tax cuts.

The regime used an output gap – taught by the IMF to calculate – to also cut taxes and print money to bridge the gap.

It was unintelligent in the extreme to teach a central bank which had gone to the IMF 16 times and triggered a currency crisis in 2012 within a program, to calculate an output gap. That was an invitation to disaster, as Singaporeans economic bureaucrats would say.

Monetary stimulus, and output gap targeting – which is legalized in the new monetary law – is a sure-fire formula to debase money and is eons away from the sound money ideology of the Thatcher administration.

There is nothing neo or otherwise liberal about printing money and output gap targeting. There is nothing liberal about expanding the size of the government based on a cookie-cutter 20 percent statistical average. There is nothing liberal about raising income tax rates either.

These are not liberal or neo-liberal ideology but pink or left leaning ‘American progressive’ ideas that brought down the UK and lost Sterling its pre-eminent status, busted the Bretton Woods, and is also creating problems in the US itself now.

Thatcher came to power promising indirect taxes, for a reason.

But there is one advantage of income taxes.

The major drawback of indirect taxes, like value added tax, is that people do not ‘feel’ the hit, since they pay in small bites.

Because these taxes do not hurt, the burden of government is not felt by the public.

Value added taxes and other indirect taxes in small percentages (but not high import duties) conforms to the Kautilya’s principle of taxation – that taxes should be charged in the same way as a bee takes honey without hurting the flower.

Income taxes on the other hand come in big chunks and are designed to hurt and make people ‘feel’ it when they pay. Income taxes and wealth taxes – sometimes imposed without any incoming cash flows – destroy savings, investible capital and future jobs, while satisfying the socialist needs of “taxing the rich”.

Progressive taxes are also illiberal in that they deny equal treatment under the law. They become expropriationary at high rates.

Transferring choice from people to politicians

In true socialist style, income taxes also take away individual choice and transfer the power of spending decisions to the politicians and economic bureaucrats, while killing economic transactions that solve people’s problems.

The consumption hit that some Sri Lanka companies are complaining of in the first quarter of 2023 is a result of taking away that choice.

This is how Geoffrey Howe boldly gave choice to the people on the street and a boost to economic decisions of the community vs the bureaucrats.

“We made it clear in our manifesto that we intended to switch some of the tax burden from taxes on earnings to taxes on spending,” Howe said in his budget speech in 1979, where the clarity of thought, reason and interconnected logic was worthy of any 19th century classical liberal.

“This is the only way that we can restore incentives and make it more worthwhile to work and, at the same time, increase the freedom of choice of the individual. We must make a start now.”

“The upper rates no longer affect only those on very high incomes. They apply – and Labour Members may find this surprising – not only to senior executives and middle managers in industry but increasingly to skilled workers, as well as to professional people and the proprietors of small businesses. These are the people upon whom so many of our hopes for initiative, greater enterprise and national prosperity must depend.

“This year I propose taking a first and significant step to deal with these complaints by reducing the rate from 33 per cent. to 30 per cent. Our long-term aim should surely be to reduce the basic rate of income tax to no more than 25 per cent.”

He followed the same strategy that Ordoliberals of West Germany had done in cutting Hitler’s progressive tax rates.

The UK’s basic rate is now 20 percent. Progressive tax rates of 60 percent failed to fix the UK in the 1970s, driving it to the arms of the IMF.

Howe also broadened thresholds.

“These reductions in the burden of income tax, which are as substantial as they are unprecedented, mean that wage and salary earners will have more money in their pockets to buy the goods and services they help to produce.

“True, the prices of a good many of these goods and services will be increased by my tax proposals. But we have done everything we can to ensure that every family in the land will have more money coming in to pay the increased bills. What is more, the choice of the way they spend their income will rest increasingly with people, and not with the Government.”

In subsequent budgets, thresholds were increased at rates higher than inflation, reversing bracket creep. Then spending was cut, bringing deficits in line and reducing the burden of the state on the people and businesses.

The lesson from tax rates

The top income tax rates were very high in the UK. So was the basic rate. But that did not help the country grow nor bring inflation down.

The important lesson is this.

It is not only that income tax reduces choice and kills economic activity and mis-direct economic activity away from serving the community’s needs to that of the priorities of the economic bureaucrats including the IMF and politicians but that high tax rates fail if money is unsound.

When there is monetary instability with a forex collecting central bank triggers shortages with a 5 percent inflation target, government borrows and debt goes up.

High tax rates, high corporate taxes failed to fix the UK. Due to operating contradictory exchange and monetary policy, UK foreign reserves plunged.

In 1976 the UK – the home of Keynes – went to the IMF for the largest loan at the time – 3.9 billion US dollars.

Foreign debt goes up when there are forex shortages as happened in Sri Lanka when stabilization measures are applied after flexible inflation targeting/flexible exchange rate crises.

Despite high rates under IMF programs, the UK suffered and its foreign debt went up. Like in Sri Lanka debt rockets in currency or economic crises, disproportionate to the actual deficits run.

“In our external policy we have also to take account of our official external debts,”“These at present amount to $22 billion – a massive increase on the $8 billion which the previous Government inherited in 1974. It is our intention to reduce that burden of external debt substantially during the life of this Parliament.”

Central Bank Independence vs Sound Money

In that budget Howe raised policy rates by 2 percent to 14 percent.

The problem is not central bank independence but whether the central bank or politicians or anyone else believes in sound money or ‘flexible’ policy where rules triumph discretion or econometrics like potential out.

He said fiscal measures alone cannot sort out the monetary morass.

“Particularly given the continuing surge in bank lending, I have concluded that there is no option but to act directly to reduce that growth. It is not enough to speak of the importance of monetary policy, unless one is prepared to carry one’s words into practice.

The Bank of England is accordingly rolling forward the supplementary special deposit scheme, or “corset”, by three months on the existing basis. In addition, the Bank is announcing, this afternoon, an increase in its minimum lending rate by 2 per cent. to 14 per cent.

Taxing everything in sight with more wealth taxes are planned in 2025, cannot fix a country, where monetary stability is denied.

The IMF can fix a country in crisis with a sudden hike in rates and an economic contraction.

But it has no consistent stable monetary framework to offer pegged central banks which collect reserves, to prevent the next crisis.

The hit from monetary instability (flexible inflation targeting/flexible exchange rates) on the fiscal framework is massive.

Peaceful countries in Latin America and Africa and Asia are driven to default by such policies. In Sri Lanka, the value added tax cut for output gap targeting was dumb, but the country tipped over the edge as debt had rocketed in the previous years and growth had declined with instability.

Several East countries cut taxes in the coronavirus pandemic – but did not print money – and saw their debt go up some, without a currency collapse.

Flexible inflation targeting and their cousins practiced by Latin America – and UK during its period of exchange controls in particular – kills growth. Each currency crisis kills consumption, makes it more difficult to collect taxes, expands deficit and debt to GDP ratios while also driving foreign borrowings to fill payment gaps from forex shortages.

IMF style ‘competitive exchange rate’ monetary instability also drives up nominal interest rates and makes the interest bill a large part of public spending.

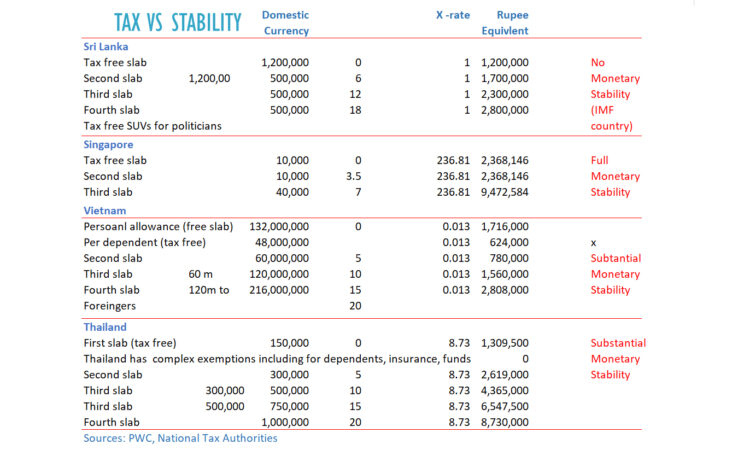

Countries with monetary stability tend to have low income and VAT rates. Among the lowest corporate tax and VAT rates and debt to GDP ratios are found in East Asian nations with the hardest money. Thailand has a 20 percent corporate income tax rate (VAT 7 percent), Singapore 17 percent (VAT 8 percent) and Cambodia (dollarized) also 20 percent (VAT 10 percent).

A good tax framework is indispensable, but it is not a substitute for monetary stability. To borrow a word from the West Germans, without stability everything is nothing.

Big Government

The revenue based fiscal consolidation ideology, which rejects spending-based consolidation, puts the entire burden of fiscal adjustment on the private sector, with no responsibility for the rulers or bureaucrats to cut spending.

In Sri Lanka, people know that there is plenty of excess spending. There are also serious doubts about the gross domestic product calculations, which will tend to reduce the tax to GDP ratio. When work in progress was added to GDP for example there are no taxes.

In the case of Sri Lanka, the magic number was decided as 15 percent of the econometrically expanded GDP at a time when it was around 12. In Ghana, which defaulted and now has about 15 percent of GDP revenues, the magic number is 18.

In Latin America, revenues are in excess of 20 to 23 percent but the pegged currencies still collapse with flexible or contradictory policies. triggering default.

The second part of the big government ideology is to hike income tax rates. Making the ‘rich pay their fair share’, a key Western leftist or ‘progressive’ slogan.

A key problem with income tax, where money is transferred directly to the hands of politicians and bureaucrats, is that it kills economic activity and individual choice. Maldives, Dubai, grew and created jobs and imported labour without income tax.

They also had superior monetary stability and not permanently depreciating currencies.