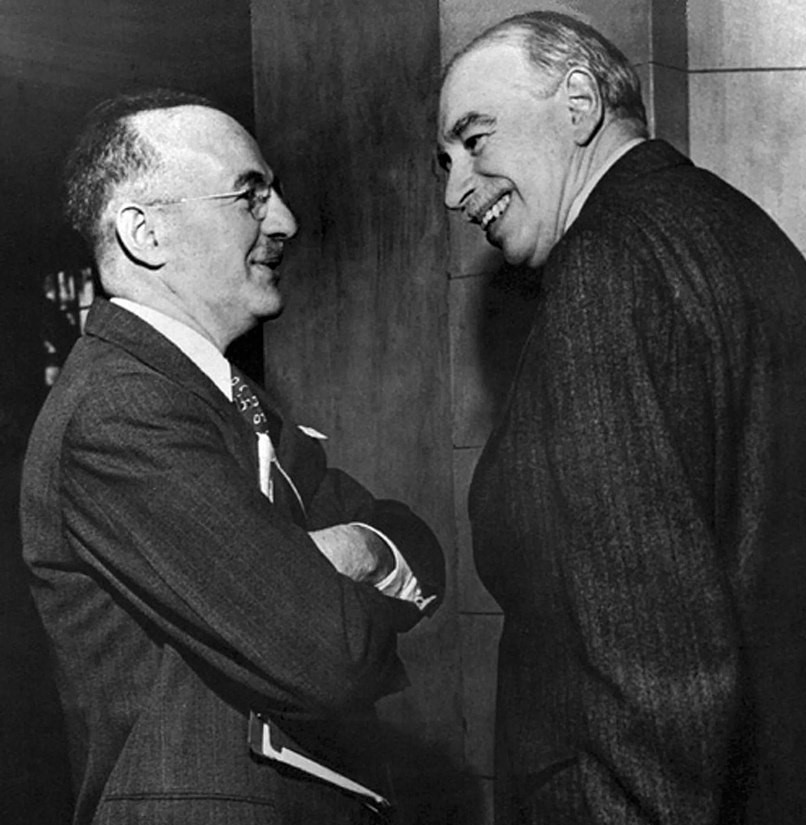

Keynes dreamed of a new global economy built upon institutions of international cooperation. At the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 he was denied his dream by the American Harry Dexter White and his fellow negotiators. Since then, historians have blamed selfish American political interests for defeating Keynes’s revolutionary ideas for a global bank and currency. Recent MSc graduate Ed Tout argues that this verdict may be unfair. Keynes’s designs suffered from fundamental flaws, flaws that economists who see a future in global digital currencies should consider carefully.

“[The proposal] is complicated and novel and perhaps Utopian in the sense, not that it is impracticable, but that it assumes a higher degree of understanding, of the spirit of bold innovation, and of international co-operation and trust than it is safe or reasonable to assume.”

John Maynard Keynes

Keynes hoped that a new global economy built upon institutions of international cooperation would be constructed after the end of the Second World War. To achieve this, Keynes proposed creating a world central bank, the International Clearing Union (ICU), in which all national central banks would hold an account. The ICU would issue a new global currency – called ‘Bancor’ – for use by the member central banks. Together the bank and its new currency would mitigate persistent trade imbalances and speculative flows of ‘hot money’ – financial flows which pursue arbitrage opportunities in periods of rapidly fluctuating interest rates – caused by floating exchange rates, thereby addressing what Keynes believed had been the twin causes of the Great Depression.

Keynes was denied his experiment. The opposition of US (United States) negotiators led by Harry Dexter White, a self-made man who chafed at the high-handedness of the aristocratic Keynes, took the ICU and Bancor off the Allied Powers’ agenda before the Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944. Since then, historians have attributed the fizzling out of the ICU and Bancor to American political interests. This verdict is unfair.

Keynes’s plans were designed for a fictitious post-war world: one that was rational, cooperative, and trusting. Consequently, his plans were based on unrealistic expectations about bureaucrats and bureaucracy, world leaders and national sovereignty, and central banks and inflation control. The American negotiators were reasonable to oppose Keynes’s plans.

Under Keynes’s scheme, there was to be one world-central bank, the ICU. All member nations would be given an annual quota of Bancor, the bank’s currency, proportionate to their share of world trade. The distribution would be managed by the ICU board of trustees. Any country’s balance of payments which slipped into deficit or surplus would either be debited or credited in Bancor until balance had been restored. In theory, all countries would be incentivised to keep their trade in goods and services balanced, forgoing ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ trade policies, which had led to the tariffs and other obstructions to trade in the 1930s.

To manage ‘hot money,’ financial stability would be maintained through the member central banks having fixed-but-flexible exchange rates between nations, and all currencies fixed to Bancor, with Bancor fixed to gold. The maintenance of these rates, the issuing of Bancor and the controlling of world gold reserves would each be the responsibility of the Governing Board of the ICU, a technocratic elite which Keynes assumed would be beholden to British and American interests.

Keynes’s plans required more than could be expected of the ICU members and ignored a series of fundamental practical, political and economic problems.

The wide-ranging mandate of the ICU would have necessitated a high level of activity by the board assisted by a large bureaucracy, a fact which Keynes omitted from his proposals but was identified by contemporary observers. Who would fill these positions?

The ICU implied an affront to national sovereignty. Given the wide-ranging powers of the governing board, each decision would have had enormous political consequences for member governments. Entrepreneurship, employment, and industrial investment would each be affected by the ICU’s controls over national interest rates and trade policies. In practice, political conflict and organisational inertia would inevitably challenge the rebalancing of world trade that Keynes envisaged.

The ICU also required centralizing foreign currency reserves for national central banks and strict capital controls for private actors, a further unacceptable invasion of sovereignty for many nations, particularly the US.

Issues of governance and political economy aside, how would the ICU begin? Keynes’ plans for the ICU gave no details on how it would acquire the capital needed to undergird Bancor.

Finally, how would the ICU be constrained? Bancor could be created at will by the Governing Board of the ICU and could fund large balance of payment deficits for member countries. But since all currencies were to be fixed to Bancor, this funding of deficits could spur a general inflation of all world currencies. If a member of the public were to keep raising their overdraft their bank would eventually run out of money – not so with the ICU.

In their afterlife, Keynes’ ideas have remained an enthralling, if ethereal, concept in monetary economics. The recent technology of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) has raised the prospect of a ‘single hegemonic currency’ (SHC) – a digital coin whose value would be linked to a basket of currencies. Once a radical idea, by 2019 it had become so influential that former Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney gave a speech advocating for its creation. The calls for a new reserve currency have become ever more strident as the monetary tightening of the Federal Reserve has caused financial ripples across the world economy.

If in the next few years central banks do decide to launch a new universal reserve currency, they would do well to listen to those who made the sensible decision to prevent the first attempt eighty years ago.