The dollar is America’s superpower. It gives Washington unrivaled economic and political muscle. The United States can slap sanctions on countries unilaterally, freezing them out of large parts of the world economy. And when Washington spends freely, it can be certain that its debt, usually in the form of T-bills, will be bought up by the rest of the world.

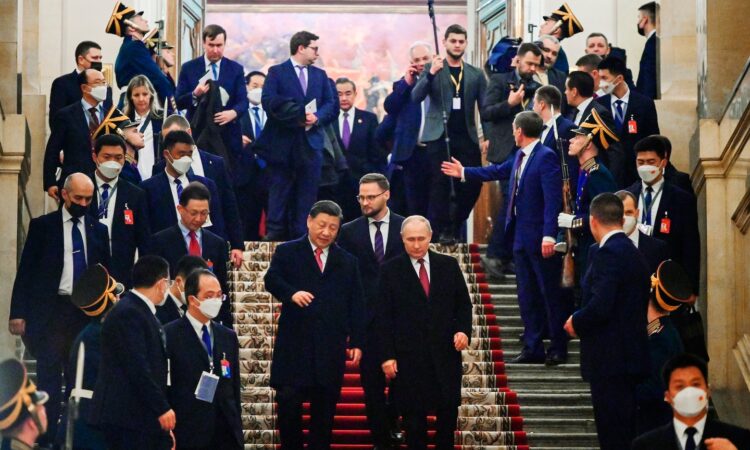

Sanctions imposed on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine combined with Washington’s increasingly confrontational approach to China have created a perfect storm in which both Russia and China are accelerating efforts to diversify away from the dollar. Their central banks are keeping less of their reserves in dollars, and most trade between them is being settled in the yuan. They are also, as Putin noted, making efforts to get other countries to follow suit.

The Biden administration has handled the economic war against Russia extremely effectively by building a coalition in support of Ukraine that includes almost all the world’s advanced economies. That makes it hard to escape from the dollar into other highly valued stable currencies such as the euro or the pound or the Canadian dollar, because those countries are also countering Russia.

What might have been a sharper turning point for the dollar’s role was President Donald Trump’s decision in May 2018 to pull out of the Iran nuclear deal and impose sanctions. The European Union, strenuously opposed to this move, watched as the dollar’s dominance meant that Iran was immediately excluded from much of the world economy, including its trading partners in Europe. Jean-Claude Juncker, then president of the European Commission, proposed enhancing the euro’s role internationally to shield the continent from “selfish unilateralism.” The commission outlined a path to achieve this goal.

That hasn’t happened; there remain too many fundamental doubts about the future of the euro itself. Dollar dominance is firmly entrenched, for many good reasons. A globalized economy needs a single currency for ease and efficiency. The dollar is stable; you can buy and sell it anytime, and it is governed largely by the market and not a government’s whims. That’s why China’s efforts to expand the yuan’s role internationally have not worked. Ironically, if Xi wanted to cause the greatest pain to the United States, he would liberalize his financial sector and make the yuan a true competitor to the dollar, but that would take him in the direction of markets and openness that are the opposite of his own domestic goals.

All that said, Washington’s weaponizing of the dollar over the past decade has led many important countries to search for ways to make sure that they do not become the next Russia. The share of dollars in global central bank reserves has dropped from roughly 70 percent 20 years ago to less than 60 percent today, and falling steadily. The Europeans and the Chinese are trying to build international payment systems outside of the dollar-dominated SWIFT system. Saudi Arabia has flirted with the idea of pricing its oil in yuan. India is settling most of its oil purchases from Russia in nondollar currencies. Digital currencies, which are being explored by most nations, might be another alternative; in fact, China’s central bank has created one. All of these alternatives add costs, but the past few years should have taught us that nations are increasingly willing to pay a price for achieving political goals.

We keep searching for the single replacement for the dollar, and there will not be one. But could the currency suffer weakness by a thousand cuts? That seems a more likely scenario. The author and investor Ruchir Sharma points out, “Right now, for the first time in my memory, we have an international financial crisis in which the dollar has been weakening rather than strengthening. I wonder if this is a sign of things to come.”

If it is, Americans should worry. I wrote last week about the bad geopolitical habits Washington has developed because of its unrivaled unipolar status. That attitude is even more true economically. America’s politicians have gotten used to spending seemingly without any concerns about deficits — public debt has risen almost fivefold from roughly $6.5 trillion 20 years ago to $31.5 trillion today. The Fed has solved a series of financial crashes by massively expanding its balance sheet twelvefold, from around $730 billion 20 years ago to about $8.7 trillion today. All of this only works because of the dollar’s unique status. If that wanes, America will face a reckoning like none before.