The writer is an FT contributing editor

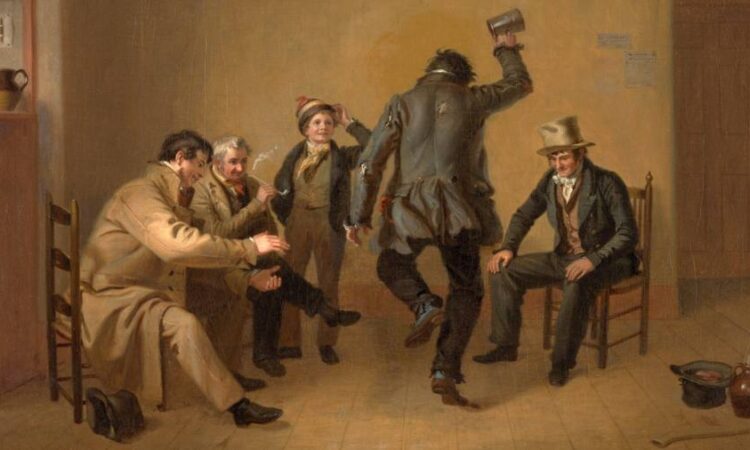

In November and December of 1787, Joseph McClain of Libertytown in Maryland drank on credit, sometimes twice a week. He ordered grogs, slings and toddies, each noted in the neat hand of the barman, Bernard McSherry. Americans in the late 18th century drank what seem today staggering amounts of whiskey and rum. Men ran up tabs with McSherry in the winter and paid them off at the end of the summer as their crops came in, so McClain’s tab does not mean that he was particularly intemperate or improvident.

On the evening of Saturday, December 15, McClain seems to have been drinking with friends. He ordered a bowl of toddy, a round of two grogs, another round of five grogs, and then with one more grog reached the end of his tab. McSherry noted a small debt outstanding from the previous year, a step that indicated he was about to bring up McClain’s account, marking the end of credit with two long slashes. Before presenting the tab for collection, McSherry added one last line: on Christmas Eve, for a single bowl of eggnog.

I have this year discovered the pleasure of reading old ledgers. McSherry’s tavern book, sold from a private collection last year to the archives at Princeton University, is banged up. It is stained on many pages, one hopes with grog. McSherry was a doodler, and left messy arithmetic on the flyleaves of his book. He kept careful records in its pages not because he wanted to, but because he had to, and so his accounts read like a short film from someone’s real life. Sometimes these lives were otherwise poorly recorded. McSherry and his brother-in-law Richard Coale, for example, kept tabs for free black men in Libertytown, one reason the ledgers did so well at auction.

Ledgers also remind us that, historically there has never been any single kind of money. Rather, in most places and certainly in Libertytown, there were different kinds of money, valuable for different reasons, working together as a part of a system with rules that everyone understood. Anyone looking through the records of McSherry’s tavern or Coale’s store to prove that money is either a social system of credit or market system of metal will be disappointed.

McSherry’s book at first suggests a pure credit system, based on local trust. Book credits were common not just among tavern keepers in America, but with the trades as well. In Libertytown, some drinkers ran up a tab and then paid it down with bushels of oats. Sometimes they’d transfer their debts to each other, with McSherry’s records functioning like a town payment system. After McClain’s debt was brought up, he worked some of it off by cutting wood. The rest remained on the book, secured by a note from a John Loveman, a standard practice for questionable debts.

But most of the men with tabs simply paid them off with a note that read “by cash”. The word cash is frustrating for monetary historians. There’s never a description of what cash was in ledgers, because everyone at the time already knew. In colonial Maryland, paper money had been relatively well managed, anchored to a fund invested in the stock of the Bank of England. With that connection severed, Maryland in the 1780s tried several experiments, issuing both shillings and dollars, secured by state land or prominent merchants.

But there seem to have been coins on the barrelhead, too. A table in the back of Richard Coale’s book notes exchange values in British sterling pounds and shillings for nine different European gold coins — doubloons, moidores, carolines, guineas. Coale also recorded an exchange rate, roughly three times sterling, for what seem to be Maryland pounds and shillings, the currency of record in Libertytown.

This means two things, neither of them a clean, satisfying story. Foreign gold coins were possibly circulating, and definitely served as a measure of value. (Maddeningly, Coale did not record a rate for silver Spanish milled dollars, the future anchor for American dollars.) And postcolonial state paper money did not collapse. It held a value that left the currency of book credits inflated over sterling, but not hyperinflationary.

McSherry’s ledger holds lessons for everyone. For bitcoin enthusiasts eager to point out the collapse of private crypto exchanges based on credit, Libertytown offers an example of a spontaneous local credit exchange, with consistent rules, a central book-keeper, predictable credit limits, and different avenues of remediation for debtors. For the historians who write the history of money as the history of credit and law, the foreign hard coins in a local credit system offer a complication. For the designers of central bank digital currencies, cash — liquid, portable, anonymous — was a crucial part of clearing debts, even in a local system of trust.

And for the people who want to build decentralised finance with automatic contracts, the Libertytown books offer a single moment of human decision, an act of grace in finance: an eggnog, on credit, at Christmas.