This has potentially far-reaching implications for investment and asset allocation, some of which we are already seeing in markets.

For instance, there has been a notable switch out of equities back into government bonds, the latter of which have begun to look genuinely attractive again, with even the 10-year German bond recently trading on a 3pc plus yield.

Meanwhile, all those wing and prayer equity investments, many of which wouldn’t exist at all but for the era of free money, are plainly in some trouble.

If not for the so-called “Magnificent Seven” of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla – whose share prices are up by between 33pc and nearly 200pc so far this year – the whole US equity market would be down on the year. As Albert Edwards, investment strategist at Societe Generale, puts it: “Mega-cap-weighted whoops of delight have drowned out the cries of pain elsewhere.”

As for government bonds, the rise in so-called “term premia” has been similarly dramatic, with 10-year Treasuries climbing all the way from less than 1pc at the height of the pandemic to nearly 5pc today.

When we think about what determines these long-term rates of interest, it is common to argue that since there is very little chance of default in major advanced economies, the “term yield” is merely the sum of what investors think official policy rates will add up to by the time of maturity.

This is a nice theory, but it seems to wholly ignore supply and demand factors, and in particular that supply has risen off the scale in recent years, with unprecedented quantities of net issuance.

With central banks now absent from the market, demand has on the other hand somewhat waned, notwithstanding the better value that bonds now offer.

Those central bank purchases – quantitative easing (QE) – massively distorted the market. At its peak, for instance, the Bank of England owned around a third of the national debt, or more than £1 trillion worth in nominal terms.

During the pandemic, when debt issuance reached record levels to pay for lockdown strategies, the Bank of England was buying up the stuff almost as fast as it could be issued. That’s now stopped, and indeed is being slowly reversed. The Bank recently raised its planned asset disposal programme to £100bn a year.

Unless there is a change of mind, there’s no more support coming from that quarter. And I’d be amazed if the Bank did indeed change its mind. The economic downsides of QE and other forms of financial repression – in terms of fuelling credit and asset price bubbles, further widening wealth inequalities, and encouraging fiscal profligacy – are now widely recognised.

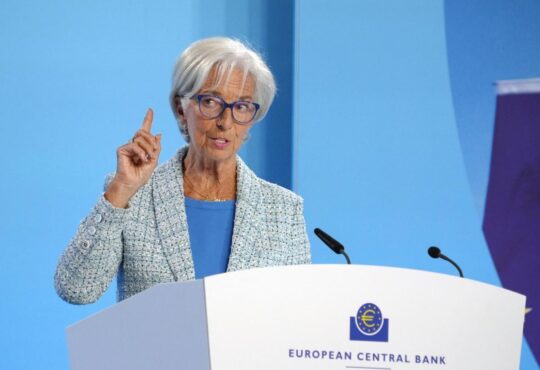

Central banks will be wary about reaching for this particular policy tool in future. Those that do will be accused of not being truly independent, and their national currencies will suffer accordingly, further fuelling inflationary pressures.

Higher interest rates have in turn driven big increases in debt servicing costs, leaving governments chasing their tails in trying to get on top of burgeoning fiscal deficits. The glut in debt issuance therefore continues apace.