By Atul Bhatia, CFA

The financial press has been full of headlines lately on the death of the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency. While we think this view is wrong—or at least so premature as to be indistinguishable from being wrong—we think equally damning is that the predicted dramatic falls in U.S. asset prices are likely pure hyperbole.

The reality is that currency changes are just one component of a complicated macroeconomic backdrop, and we believe the migration toward a global multicurrency reserves position will ultimately prove to be just as boring as it sounds.

Reserve impact

Currency reserves are held by central banks and foreign institutions for several reasons, but primarily to provide stability and to purchase key imports during periods of domestic or global economic crisis. For decades, the U.S. dollar has been the currency of choice for reserves—to the tune of roughly US$7 trillion.

Despite the name, we think the real benefit to a country of having reserve currency status has little to do with foreign exchange—a stronger U.S. dollar tends to help inflation by making imports cheaper and to hurt exporters by making it tougher to sell goods abroad. However, both effects are generally minor.

Instead, the greenback’s reserve status has had the largest impact by providing funding for the U.S. government. Dollar reserves are almost always held in U.S. Treasury or agency bonds, highly liquid securities that tend to perform well as global economic risks mount, making the investment particularly valuable precisely when reserves are needed. As a result, foreign demand for dollar reserves has created concurrent demand for U.S. government debt.

Slowly at first, then more slowly

Where the recent commentary goes wrong, in our view, is in confusing what economists refer to as stocks and flows. Because of reserve holdings, foreign institutions are sitting on US$7 trillion in Treasuries. A rapid unwinding of that stock of bonds would be negative, but it’s also incredibly unlikely, as we discuss below.

The more likely path for de-dollarization in reserves is through redirecting the flows of newly created reserves. This process has already begun. The greenback is now about 58 percent of global reserves compared to nearly 73 percent in 2001. Critically, the reallocation came through changes in new investment flows, not by selling the stock of existing positions. We see that trend continuing.

If that happens, we would expect to see slightly reduced demand for U.S. bonds at future Treasury auctions, potentially pressuring yields upward. But impacts are likely to be small. Overseas investors have bought just under 17 percent of Treasury notes and bonds issued in 2023, a quantity easily replaceable with existing demand, as auction orders routinely double the bond offering size. Publicly available data does not allow us to calculate the yield impact with precision, but we feel confident saying it would be a matter of basis points, not percentages, and easily manageable for the U.S. economy.

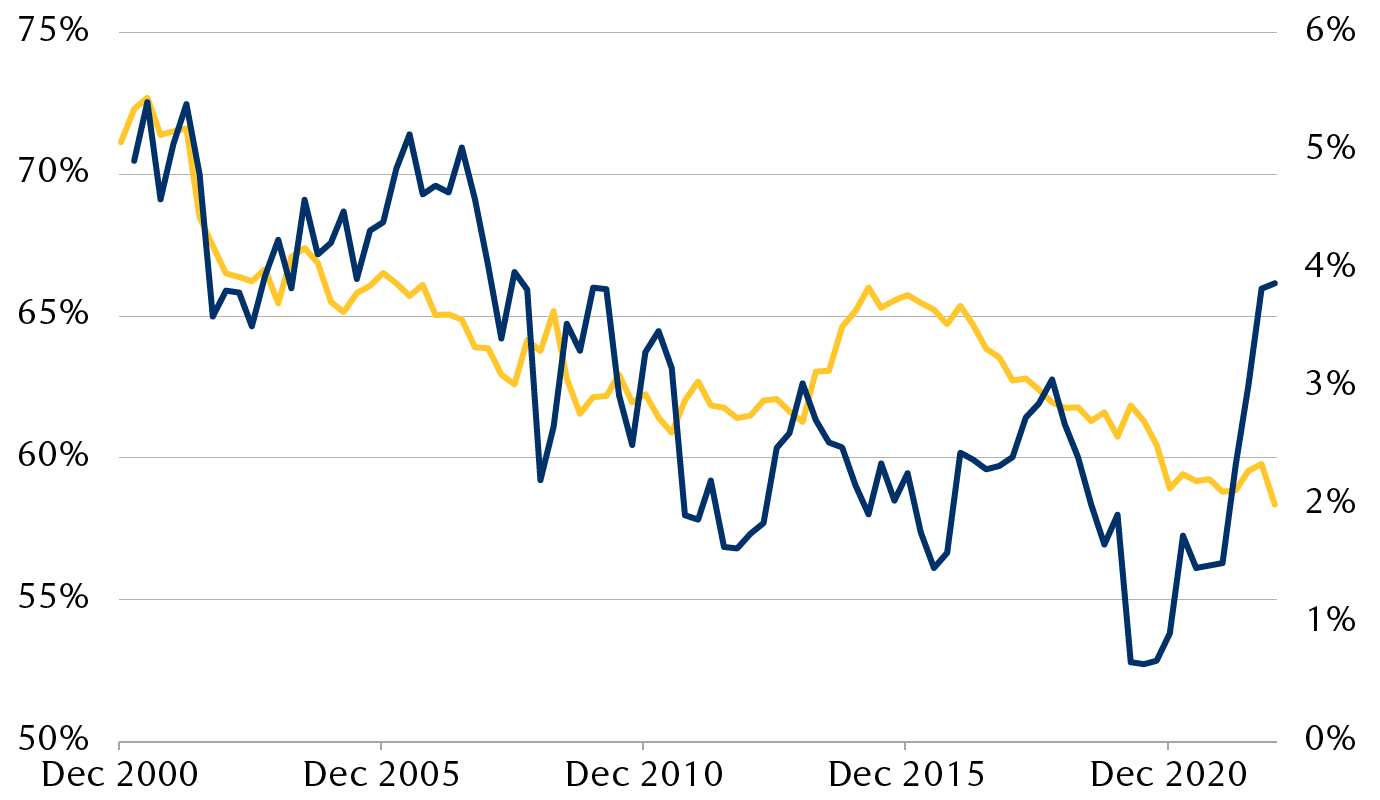

Yields fall alongside dollar’s reserves dominance

Reserve buyers just one factor in complicated pricing mosaic

Line chart showing the U.S. dollar declining from 72% of global reserves to 58% between December 2000 and December 2022. During the same period, 10-year Treasury yields fell to 3.88% from 4.92%.

- Percentage of global currency reserves held in USD (LHS)

- Yield on 10-yr U.S. Treasury (RHS)

Source – RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; data through 12/31/22

One reason for our confidence is history. The dollar’s share of world reserves has dropped by 15 percent since 2001, a time that saw 10-year government bond yields fall over one percent. Clearly, factors other than reserves influence Treasury demand. More broadly, we can look to the UK. Sterling fell to 35 percent of global reserves by 1960 from roughly 70 percent in 1940. While there were some difficult years for the UK in that range, we argue they were largely a consequence of the war debt rather than any currency implications. Regardless of the cause, the worst the UK experienced in that time was a recession, not an apocalypse.

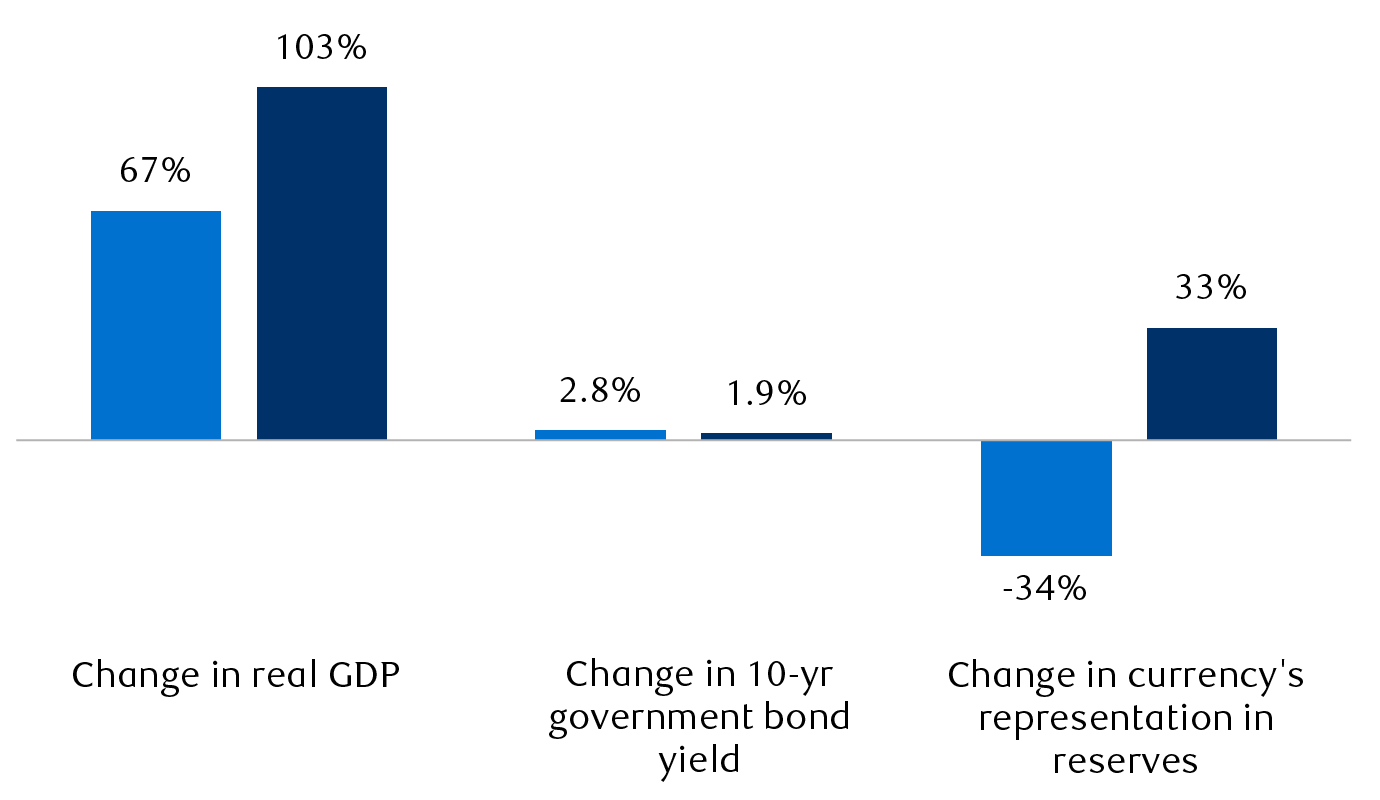

Good to be king; not bad to be ex-king

Reserve currency transition benefits U.S., but UK does well (1940–1960)

Column chart comparing the changes in bond yields, real GDP, and currency reserves representations for the U.S. and UK between 1940 and 1960. The data shows U.S. real GDP increasing 103% in that time compared to 67% for the UK and bond yields increasing 2.8% in the UK and 1.9% in the U.S. while reserve participation declined 34% for UK’s pound sterling and increased 33% for the U.S. dollar.

Source – RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg, International Monetary Fund, Bank of England, Statista, GovInfo

Limited alternatives limit options

Some commentators posit a more radical shift in currency positioning, where dollar reserves are dumped on the open market. The idea makes good copy but it’s hardly practical. To start, it’s entirely counterproductive for the sellers. Reserves are held by exporting nations. It’s hard to see how tanking the economy of their biggest customer would benefit them. The resulting global turmoil would almost certainly destabilize their own economies more than the U.S. dollar and create a self-inflicted domestic political crisis.

The other fatal flaw, in our view, is that there is no viable replacement for the dollar, as has been discussed previously. The euro can absorb some redirected flows from new reserves accumulation, but the math on shifting the US$7 trillion stock of dollar reserves into a German bond market with €2 trillion outstanding does not work. Not to mention that the eurozone would almost certainly look to limit inflows from countries that had just weaponized bond markets.

The lack of existing alternatives has not stopped some of the more enthusiastic de-dollarizers from speculating on the creation of a new BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) currency. While some sort of payments facility mechanism between the countries is a possibility, we think a common currency between such disparate economies with no fiscal union flies in the face of reason. No central bank has an easy task, but setting a coherent monetary policy for that mix of commodity importers and exporters is a Herculean one. We wish them luck in deciding between rate cuts and hikes if oil prices fall, hurting Russia while causing potential booms in India and China.

A monetary mosaic

Reserve currencies are ultimately about confidence: confidence in political stability, confidence in the rule of law, confidence in economic policymaking and, most importantly, confidence that in times of trouble and crisis people will want to own the currency you are holding. The U.S. may not measure up as well as it once did in these areas, but the dollar is not in competition with its former self. And looking at today’s alternatives, we believe there is no viable means to replace the stock of reserves held in dollars.

In our view, any evolution in reserve holdings is likely to be a gradual process, and rather than prove a catastrophe for asset prices, we see it as just one more background factor in the complicated macroeconomic environment.

RBC Wealth Management is a business segment of Royal Bank of Canada. Please click the “Legal” link at the bottom of this page for further information on the entities that are member companies of RBC Wealth Management. The content in this publication is provided for general information only and is not intended to provide any advice or endorse/recommend the content contained in the publication.

® / ™ Trademark(s) of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under licence. © Royal Bank of Canada 2024. All rights reserved.