Not only do there exist practical difficulties in pursuing a common BRICS currency, but the other constituents of the bloc may consequently end up increasing their reliance on China

This is the 143rd in the series–The China Chronicles.

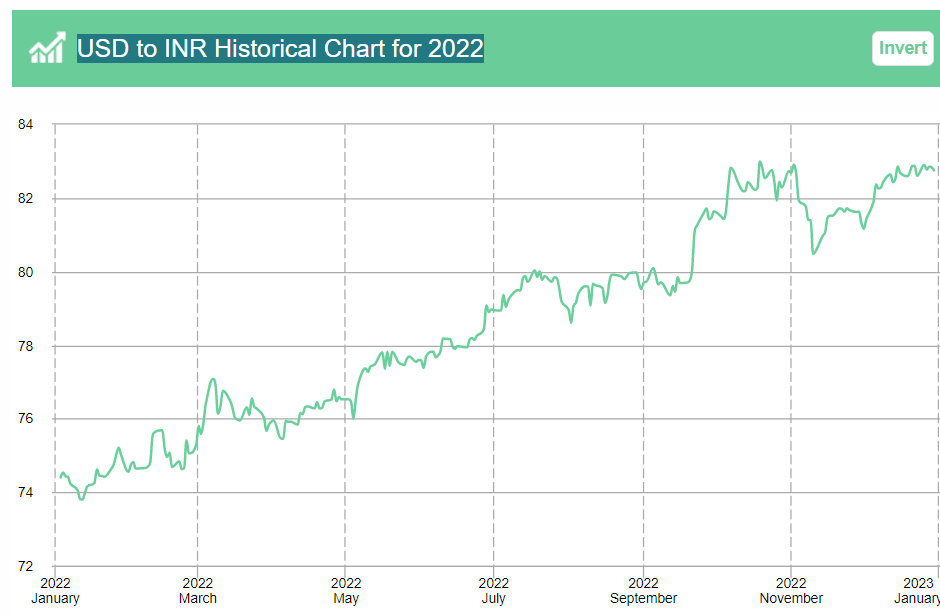

The US dollar’s appreciation since early 2022 has ignited hope in emerging markets of decreasing their reliance on the global reserve currency, and of consequently shielding themselves from the interest rate cycles driven by the Federal Reserve (see Figure 1). This is unsurprising given the way the Fed’s hiking cycle over 2022 demonstrated—once again—how intimately global financial markets are connected to those in the US, and it showed the urge to shield against US-led sanctions of the nature imposed on Russia over the Ukraine war or perhaps in the nature of secondary sanctions – even if these are less stringent.

Figure 1: This chart shows USD to INR Exchange Rate History for 2022 (exchange-rates.org).

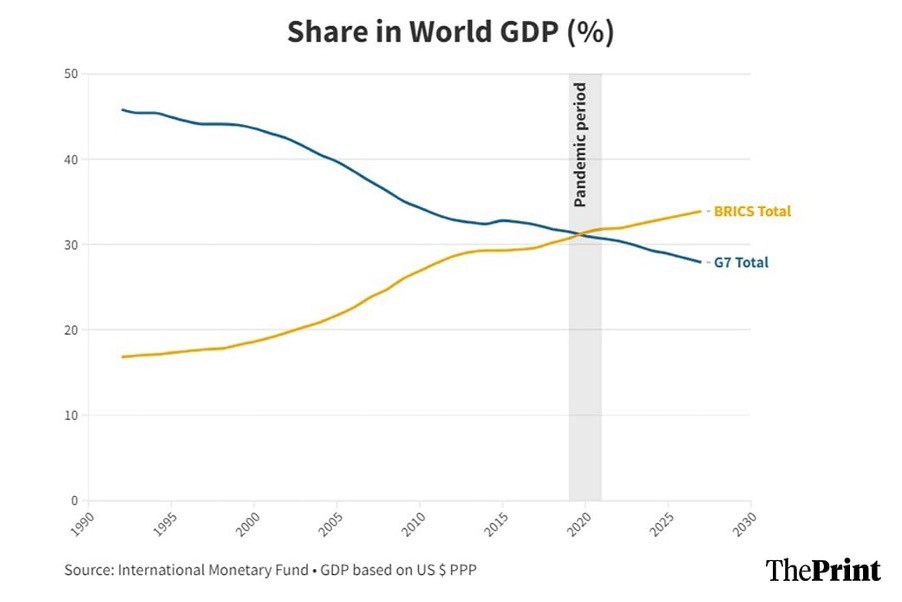

With Moscow claiming to champion the development of the BRICS currency and Rio de Janeiro making supporting noises, the portrayal surrounding the stability of the dollar’s rule has come under increasing scrutiny. As expressed by American economist Richard Baldwin, “Europe is a museum, Japan is a nursing home, and China is a jail.” While he is not incorrect, a BRICS-supplied currency could be different because in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), the grouping as a whole surpasses not only the US but the complete G-7 weight class in its entirety.

Figure 2: This chart shows that led by China and India, the 5 BRICS nations now contribute more to global GDP than the G7 (theprint.in)

However, there is nothing novel about overseas nations aspiring for a measure of independence from the US dollar. But these have yet to fructify. As per an estimate, the dollar presently Further, the Kremlin’s repeated utilisation of deception as a tool of statecraft arouses suspicion regarding Russia’s commitment to the cause of a common BRICS currency. For now, on a plethora of practical questions, the answers remain unclear.

Not vaguely feasible as a monetary union, the constituent economies of the BRICS are drastically disparate with respect to international trade, economic growth, and global integration of capital markets.

Feasibility

The issue is that the BRICS does not constitute a particularly robust economic grouping. It seeks to mate an existing economic giant in China with an emerging power in India and three much smaller economies based on commodity exports.

Not vaguely feasible as a monetary union, the constituent economies of the BRICS are drastically disparate with respect to international trade, economic growth, and global integration of capital markets. While the Russian economy was the worst performer within the grouping in 2022, Brazil and South Africa have also been embattled in the absence of robust commodity prices providing support for low interest rates and increasing creation of domestic credit.

To be sure, the BRICS accounts for 18 percent of global trade, while the European Union accounts for However, the contrast between BRICS members in terms of economic growth is sharp, with real GDP per capita at constant prices over 2008-2021 rising 138 percent for China, 85 percent for India, 13 percent for Russia, and 4 percent for Brazil. South Africa, in fact, witnessed a 5 percent contraction over the same period. Notably, though, it is not this disparity that constitutes the principal issue in the BRICS operating as an economic union.

Chinese influence and objectives

An important trading partner to commodity exporting countries, China’s sway over sanctioned Russia has only increased during the Ukraine war. According to a US Congressional Research Service report in May 2022, Moscow has been importing billions of dollars’ worth of machinery, electronics, base metals, vehicles, ships, and aircraft from China.

In the consumer electronics space, Chinese brands, which accounted for approximately 40 percent of the Russian smartphone market at the culmination of 2021, have now seized the industry with a 95 percent market share as per market research firm Counterpoint.

As per Russian research firm Autostat, Chinese car brands, like Havel, Chery, and Geely, have experienced an enormous expansion in their market share from 10 percent to 38 percent during the year after the exodus of Western brands, and that share is expected to increase further in 2023. In the consumer electronics space, Chinese brands, which accounted for approximately 40 percent of the Russian smartphone market at the culmination of 2021, have now seized the industry with a 95 percent market share as per market research firm Counterpoint.

It is also evident that China’s strategic goals are not particularly in line with those of other BRICS members. One of Beijing’s objectives, for instance, is to find havens to store external surpluses in assets other than US Treasuries—outside the grasp of the US Office of Foreign Assets Control. Though no other BRICS country can offer such investment avenues with the requisite liquidity, they can offer investment prospects in raw materials. Like in the case of the Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing prefers to establish and exercise authority in such scenarios.

Russia and the Gulf energy exporters prefer accumulating “rainy day” sovereign wealth funds away from the US. The alternative, though, is not a varied bloc of expanding economies. It is basically a single assertive country, China—a gargantuan blotting paper for energy and other raw materials.

Conclusion

The balance of payments between the US and the BRICS deserves more attention from policymakers than it receives, given that the former and latter run a deficit and surplus respectively. Indeed, the nature of these economies must be comprehended.

Consumers in the BRICS countries suffer from low purchasing power, thereby necessitating—or at least incentivising—export-driven models of economic growth. BRICS nations therefore accumulate vast reserves of US dollars to ensure that their currencies trade artificially cheap against the US dollar in international currency markets, and to consequently render their exports competitive. For instance, under a free market regime, US dollar inflows into China would boost and diminish the value of the yuan and the US dollar respectively. This would increase China’s ability to import and consequently increase US exports to China. But this has not materialised because countries like China utilise a type of ‘currency mercantilism’ involving the hoarding of US dollar reserves and deep export subsidies, despite the cost to domestic consumers.

Just as geopolitical drivers such as increasing usage of the dollar-based international payments regime for enforcement of financial sanctions incentivise the quest for an alternative international medium of exchange, there also exist potential geopolitical dampeners to the prospect of a BRICS common currency in the form of tensions between Beijing and New Delhi due to the former’s expansionist tendencies.

Further, just as geopolitical drivers such as increasing usage of the dollar-based international payments regime for enforcement of financial sanctions incentivise the quest for an alternative international medium of exchange, there also exist potential geopolitical dampeners to the prospect of a BRICS common currency in the form of tensions between Beijing and New Delhi due to the former’s expansionist tendencies. The prolonged standoff along the Line of Actual Control is a case in point.

If the BRICS countries actually seek de-dollarisation, their economies would require significant rebalancing involving permitting their currencies to appreciate and thereby encourage imports. But as witnessed in Japan after 1985, this is very hard to achieve and comes with its own plethora of issues. Thus, not only do there exist practical difficulties in pursuing a common BRICS currency to diminish US dollar’s international dominance, but the other constituents of the bloc may consequently end up increasing their reliance on China.

Aditya Bhan is a Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.