Between April-end 2014 and now – roughly the time the Narendra Modi-government has been in office – the rupee has depreciated by 27.6% against the US dollar, from Rs 60.34 to Rs 83.38.

That’s marginally higher than the 26.5% from April-end 2004 to April-end 2014: The rupee fell from 44.37 to 60.34 to the dollar during that period when the previous Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) was in power.

The EER is measured by an index similar to the consumer price index (CPI). The CPI is the weighted average retail price of a representative consumer basket of goods and services for a given month or year, relative to a fixed base period. The EER is an index of the weighted average of the rupee’s exchange rates vis-à-vis the currencies of India’s major trading partners. The currency weights are derived from the share of the individual countries to India’s total foreign trade, just as the weights for each commodity in the CPI are based on their relative importance in the overall consumption basket.

There are two measures of EER.

The first is the Nominal EER or NEER.

The Reserve Bank of India has constructed NEER indices of the rupee against a basket of six and also of 40 currencies.

The former is a trade-weighted average rate at which the rupee is exchangeable with a basic currency basket, comprising the US dollar, the euro, the Chinese yuan, the British pound, the Japanese yen and the Hong Kong dollar. The latter index covers a bigger basket of 40 currencies of countries that account for about 88% of India’s annual trade flows.

The NEER indices are with reference to a base year value of 100 for 2015-16: Increases indicate the rupee’s effective appreciation against these currencies and decreases point to overall exchange rate depreciation.

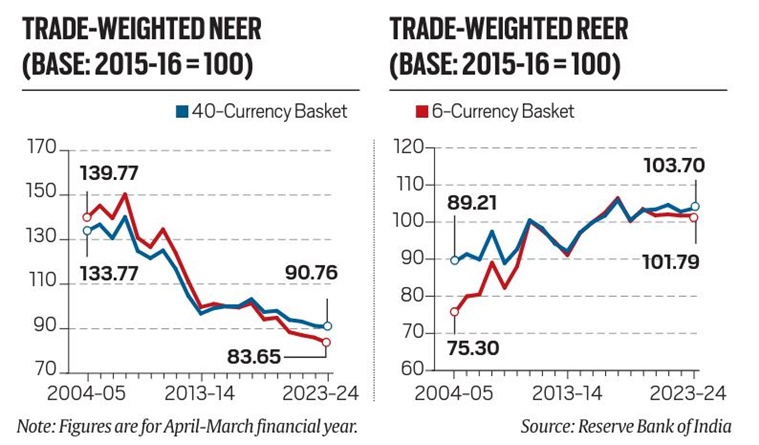

Chart 1 shows that the rupee’s 40-currency basket NEER has fallen by around 32.2% (from 133.8 to 90.8) between 2004-05 and 2023-24. The decline is even more – 40.2%, from 139.8 to 83.7 – for the narrower 6-currency basket NEER. During the same period, the rupee’s average exchange rate against the US dollar dropped by 45.7%, from Rs 44.9 to Rs 82.8.

Simply put, the rupee’s “effective” depreciation of 32.2-40.2% against the currencies of all major trade partners of India over the last 20 years has been lower than its corresponding depreciation of 45.7% against the US dollar alone for this period. The reason for that is its weakening less relative to other currencies than vis-à-vis the dollar.

The chart, moreover, reveals that the bulk of the NEER decline happened during 2004-05 to 2013-14. The rupee, in fact, strengthened thereafter till 2017-18, before resuming its weakening trend – albeit at a slower pace than during the UPA period.

The second measure is the Real EER or REER.

The NEER is a summary index that captures movements in the external value of the rupee against a basket of global currencies. However, the NEER does not factor in inflation, which reflects changes in the internal value of the rupee.

To illustrate, the Indonesian rupiah has fallen 8.5% against the US dollar in the last one year. The Indian rupee has depreciated much less, by 1.7%, during this period. But India’s annual CPI inflation rate, at 4.9% for March, stood above Indonesia’s 3.1%. Thus, the Indonesian currency’s domestic purchasing power has suffered less erosion relative to its international purchasing power, whereas it has been the reverse for the rupee.

The REER is basically the NEER that is adjusted for the inflation differentials between the home country and its trading partners. If a country’s nominal exchange rate falls less than its domestic inflation rate – as with India – the currency has actually appreciated in “real” terms.

Chart 2 maps the rupee’s trade-weighted REER for the last 20 years, taking a base year value of 100 for 2015-16. The rupee, it can be seen, has strengthened in real terms over time, while ruling at 100 or above in 9 out of the Modi government’s 10 years. This is opposite to the trend of weakening if one takes only the rupee’s NEER or its exchange rate with the US dollar.

If one assumes that the rupee was “fairly” valued in 2015-16, when the EER indices were set to 100, any value above 100 signifies overvaluation. The rupee is, to that extent, overvalued today in terms of its REER.

Any increase in REER means that the costs of products being exported from India are rising more than the prices of imports into the country. That translates into a loss of trade competitiveness – which may not be quite a good thing in the long run.