From the Brexit vote to the mini-budget in September 2022, economic policy in the UK has been uncertain, a feature more commonly associated with emerging markets. LSE’s Liliana Varela examines whether, should this uncertainty continue, international investors might require a premium to invest in the UK economy and the British Pound.

In the last week, there has been an intense debate on social media about whether the UK has become an emerging market economy. On 23 September 2022, Larry Summers – Ex-US Treasury chief – even said that the UK was ‘turning itself into a submerging market‘. These are clearly strong words, but what do they imply for the UK and Sterling’s standing in the global economy?

The common theme in this discussion is Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU). This is uncertainty about government policies related to inflation, sovereign debt sustainability, interest rates, central bank independence, tax cuts, the fiscal deficit, and so on. While this uncertainty raises many difficult questions, research has shown that EPU affects currency movements and returns in currency markets.

To fix ideas, let us first define excess returns in currency markets. In the absence of excess returns, a US investor would be indifferent between investing one US dollar in the US for a return (1+it$) or converting the US dollar into foreign currency (at an exchange rate St), investing in that country for a return (1+it) then converting the proceeds back into US dollars at an expected exchange rate (Et St+1). This condition is called the Uncovered Interest Rate Parity (UIP) and states that investors should not perceive excess returns from investing in different currencies.

Yet a long line of research in international macroeconomics and finance shows that this condition tends to fail and evidence of excess returns are often reported. Kalemli-Ozcan and Varela (2022) show that expected excess returns at a ‘one year horizon’ are on average 3.3 percentage points higher in emerging markets than in advanced economies. To assess whether these excess returns (what we call the ‘UIP premium’) associate with policy uncertainty, they construct a proxy for EPU. Their measure is an extension of Baker, Bloom, and Davis who, in 2016, developed an index that quantifies newspaper coverage of policy-related economic uncertainty. This index is broadly defined and captures uncertainty arising from fiscal deficit, taxes, government spending, sovereign default, currency crises, reserves, capital controls and wars, among others.

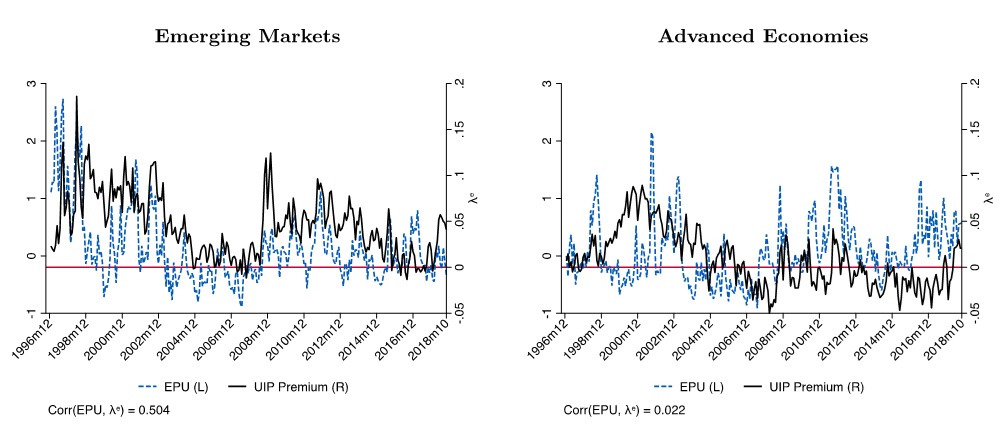

Kalemli-Ozcan and Varela show that excess returns highly correlate – by more than 50% – with economic policy uncertainty in emerging markets. The left panel of the figure below plots this correlation for 21 emerging markets over the period December 1996 to October 2018. In simple terms, this correlation implies that when facing higher economic uncertainty, investors expect to earn higher excess returns from investing in emerging market currencies. Interestingly, this correlation is almost nil for currencies in advanced economies (shown as 2% in right panel, figure 1). So, economic policy uncertainty associates with excess returns in currency markets, but this effect seems –on average- to be specific of emerging markets.

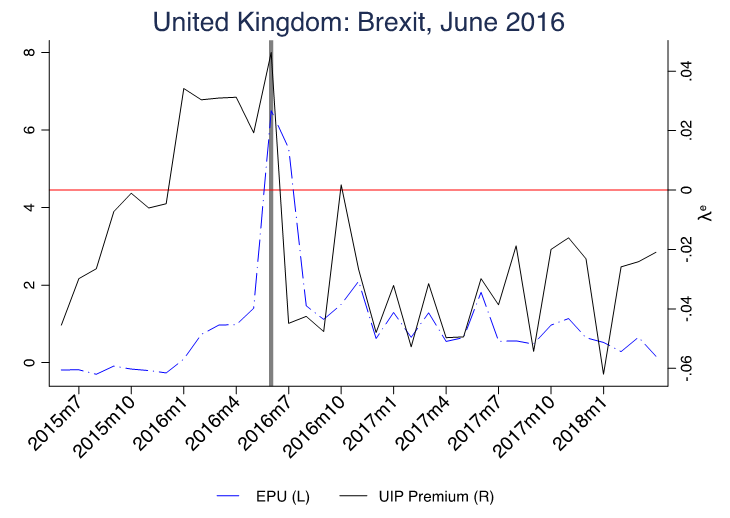

Yet, over the last years, and echoing Summers’ remarks, this signature of emerging market behaviour has surfaced in the UK: economic policy uncertainty has recently translated into the Sterling currency market. The Brexit Referendum is an example of this, as shown in figure 2. Around the time of the referendum vote, we observe a spike both in economic policy uncertainty and an increase in the UIP premium. These expected excess returns stemmed from a GBP depreciation and implied higher expected returns from investing in the pound.

Recent events in the UK seem to follow a similar trend. Wenxin Du and Jesse Schreger argue that the increase in the U.S.-UK government bond differential does not arise from default risk or an “inconvenience” of holding gilts, but from currency risk. This indicates that currency risk dominates the increase in the interest rate differential, and provides additional evidence that economic policy uncertainty affects currency markets. The novelty here is that this is happening in the UK, an advanced economy.

Has the UK economy become an ’emerging market’? Will it be? The answer is probably not. But, as events unfold, it is clear that economic policy uncertainty is affecting currency markets and could imply that investors require a premium to invest in the GBP.

#LSEUKEconomy: Explore our dedicated hub showcasing LSE research and commentary on the state of the UK economy and its future.

_____________________

Liliana Varela is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Finance of LSE and a research affiliate of the CEPR. Her research focuses on international economics and macroeconomics and, particularly, on the impact of capital flows on economic growth.

Liliana Varela is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Finance of LSE and a research affiliate of the CEPR. Her research focuses on international economics and macroeconomics and, particularly, on the impact of capital flows on economic growth.

Photo by Liza Summer.