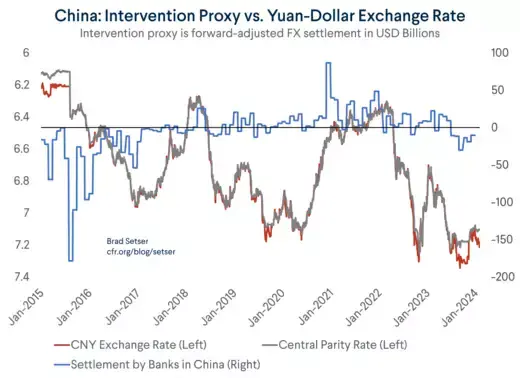

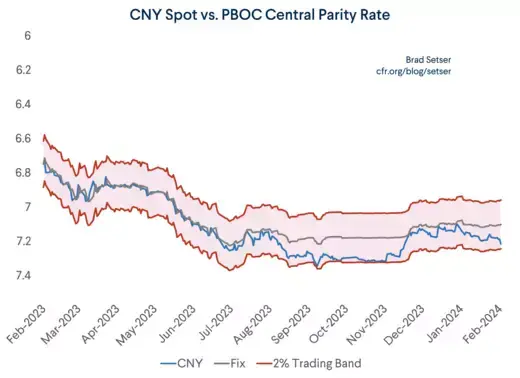

There is little doubt that China rather actively managed its currency in 2023.

For a period of time in the fall, the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC’s) central parity rate, or “fix” – the midpoint of the trading band of China’s yuan – didn’t change. The fix was fixed. That had the effect of blocking the yuan from depreciating further, as the yuan is limited to a range of ±2 percent around the fix.

Trading bands are a well-known approach to currency management, and bands that turn into pegs when a currency is stuck at one end are hardly unknown.

More on:

The puzzle here isn’t the presence of a band, but how the band was maintained.

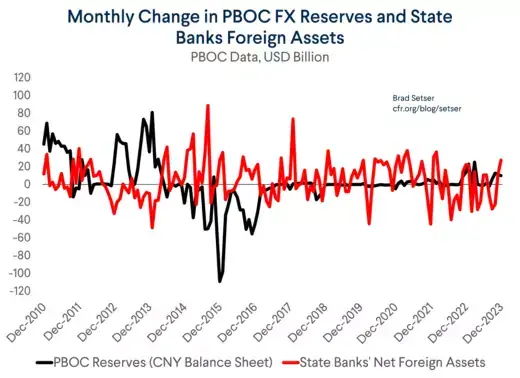

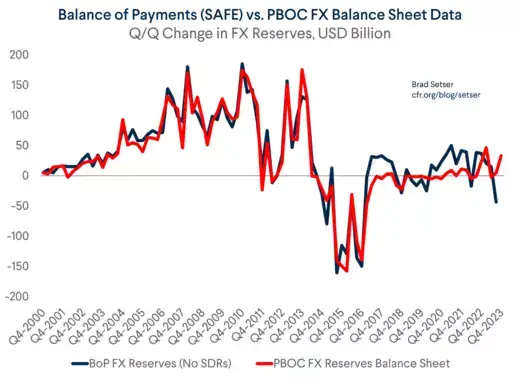

Usually, a band is maintained by the central bank, which buys or sells foreign exchange as needed to keep the currency’s market price within said band. But that doesn’t seem to be what China did. The foreign currency balance sheet of the PBOC was totally flat for most of 2023 (hence the PBOC’s assertions that it is mostly out of the currency market). There were adjustments to banks’ required reserve ratio that freed up a bit of foreign exchange held in the banks’ reserves, but the PBOC doesn’t seem to have used any of its own funds to keep the yuan inside the weak edge of the band from August through October.*

Indeed, the PBOC added foreign exchange to its balance sheet in the fourth quarter, and thus ended 2023 with about $100 billion more in foreign exchange than it started the year.

That’s a strange result for a period when the yuan was under pressure to depreciate (it was at the weak edge of the band set by the fix, not the strong edge) and one would normally expect the PBOC to be selling reserves to manage and smooth the yuan’s fall.

China thus presents a puzzle – a currency that appears managed, with the central bank balance sheet of a country that has a nearly free float. And a country that should be shedding reserves to defend the weak edge of a band is instead reporting higher reserves.

More on:

That is a challenge for both the Treasury – as its core methodology for doing foreign exchange surveillance relies entirely on changes in a country’s formal reserves to determine if there is unwarranted intervention** – and the IMF, which, at least in theory, is responsible for assessing whether a country’s foreign exchange market practices impede orderly balance of payments adjustment.***

That’s difficult when the country’s market practices aren’t well understood, or well-captured by any standard metrics or models.

However, with a bit of digging, it is possible to get a relatively clear understanding of how the PBOC avoided intervention when the fix was fixed and the yuan was at the weak edge of the band: there are multiple reports suggesting that the PBOC leaned on China’s state banks to do its dirty work.

Reuters reported that “China has sought to stabilize the yuan by orchestrating buying by state banks and giving market guidance to bankers” in its well-done review of the PBOC’s effort to stabilize the yuan last year.

The Reuters story reads a bit like Politico stories about the Trump administration’s first year (“based on interviews with 40 unnamed sources, the White House is in chaos”). It is worth considering carefully, as it suggests that China has developed a new strategy for intervention that goes well beyond standard jawboning (emphasis added):

“Interviews with 28 market participants show at least two dozen cases where regulators closely and frequently steered market participants through a range of coordinated actions this year to resist strong downward pressure on the yuan … efforts to manage the yuan involved more targeted and specific directions to banks and currency market participants … for example, whenever momentum seemed against the yuan, state-owned banks quietly became buyers, the traders said. This generally happened around psychologically significant currency levels and seemed aimed at containing volatility … On Sept. 8, the yuan struck a 16-year low. A few days later, managers at eight major banks were summoned to Beijing to meet PBOC officials, according to five banking sources, two of whom attended the meeting. They were told companies wishing to buy more than $50 million would need approval from the PBOC, three sources said. Bankers were also told they needed to cut spot trading, stagger dollar buying and not hold net long dollar positions at the end of any trading day.”

Bloomberg has reported the same, more or less:

“Chinese authorities told state-owned banks to step up intervention in the currency market this week, in a push to prevent a surge in yuan volatility, according to people familiar with the matter.”

“Traders said that both official limits on the exchange rate’s movement and indirect intervention from state banks buying up the currency had helped snap the renminbi’s protracted losing streak, after the Communist party’s Politburo voiced support for a ‘basically stable’ exchange rate at an ‘appropriate level of equilibrium’ in a statement on July 24 … ‘We’ve seen a lot of dollar-renminbi selling right after the market open, especially from the Chinese banks,’ said one veteran currency trader at a foreign lender based in mainland China. Another forex trader at a European bank in Shanghai said state banks had become heavy net buyers of the renminbi after the Politburo’s statement.”

So, China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) summoned the key banks – who are all owned by the state and basically are the market on a day-to-day basis – and gave them operating instructions.

Moreover, Reuters highlights that onshore dollar holdings are effectively a policy variable that the PBOC uses to limit its formal intervention (by incentivizing depositors to hold or sell dollars to help manage the currency). Those deposits fell in 2023 even as the U.S. raised dollar interest rates and the PBOC cut yuan rates.

Why? Simple:

“In June and July, the China FX Market Self-Regulatory Framework, which is overseen by the PBOC, told major state-owned banks to cut dollar deposit rates, which would encourage exporters and households to switch dollar receipts into yuan, market watchers said.”

The Financial Times drove the point home:

“Among other supportive measures, China’s largest state banks have lowered their dollar deposit rates several times in recent months in line with guidance from central authorities seeking to prevent domestic stockpiling of dollars and ease depreciation pressure on the renminbi, according to bank statements and traders.”

The PBOC in the past has said that the rising foreign assets of the state banks were not a sign of indirect intervention, as the banks were simply balancing their domestic dollar deposits. I think that argument now needs to be assessed in a new light. As does the Financial Times:

“Onshore dollar deposits at Chinese banks have previously been mobilized as a form of invisible reserves to relieve pressure on the renminbi … as an indirect but effective alternative to burning through the foreign reserves held by the PBoC.”

There isn’t an easy way to assess the amount of indirect intervention that China did to support the yuan, though it was likely substantial.

Indeed, one of the paradoxes of China’s management – particularly when it is resisting depreciation – is that a clear signal that the yuan isn’t going to depreciate reduces the incentive to bet on further depreciation. Thus, by sending strong signals that further depreciation is off the cards, the market can balance based on inflows from exporters converting dollars back into yuan.

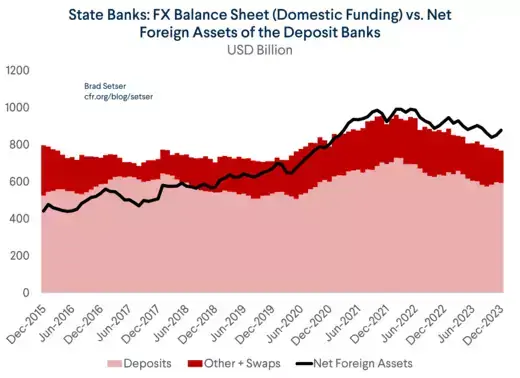

But if needed, the state banks do have plenty of assets at their disposal to support the yuan. That is what appears to have happened in the third quarter if the banking data for the deposit-taking banks (the State Commercial Banks, but not the three main state policy banks) is to be believed.

The balance of payments data tells a slightly different story, as it shows (gulp) reserve sales in the third quarter and a smaller reduction in the foreign assets of the state banking system. As usual, the Chinese data doesn’t quite line up.

But the broad story is the same in both data sets over the full year – less direct intervention, and more indirect intervention.

To make any assessment more complicated, however, there are credible and consistent reports that the intervention is funded by foreign exchange raised through swaps. Such activity might not appear in the reported net foreign asset position data.

A bank that raises dollars through the swaps market (borrows dollar by swapping yuan for dollars) has an obligation to swap the dollars back for yuan in the future. This is a forward commitment to sell dollars.****

The bank, of course, maintains a balanced position if it holds onto the dollars it obtained through the swap market. Its on-balance sheet dollars would rise relative to its on-balance sheet dollar liabilities, with an offsetting increase in off-balance sheet liabilities.

But if the bank sells the dollars it raised in the swap market in the spot market, there is no change to the banks reported foreign currency balance sheet.

And that seems to often be the case:

“China’s state banks were in the FX market on Tuesday afternoon, intervening to prop up the yuan: major state-owned banks buying yuan and selling US dollars (by swapping yuan for dollars in the onshore swap market, then selling the dollars in the spot market) after Moody’s cut China’s outlook to negative in the afternoon the intervention gathered pace … The state banks take such actions under instruction from the People’s Bank of China in order to slow the yuan decline. While state banks do have reasons for trading their own accounts and views, such obvious, coordinated action is under ‘advice’ from the PBOC.”

China’s state banks are credible swap counterparties because they directly have enough dollars on their balance sheet to ensure repayment of the swap, and they can indirectly draw on the PBOC’s resources, if necessary, to close their open position. Indeed, a big foreign currency balance sheet creates a lot of options for backdoor support.

There are, of course, other ways China can use its state sector to support the yuan. A recent Bloomberg story indicated that the State Council is working on a plan to use $278 billion in offshore assets of China’s state firms to support the stock market:

“Policymakers are seeking to mobilize about 2 trillion yuan ($278 billion), mainly from the offshore accounts of Chinese state-owned enterprises, as part of a stabilization fund to buy shares onshore through the Hong Kong exchange link.”

That would also help to support the yuan.

All technical, but the bottom line is that it is imminently possible for the state banks to have actively intervened in the market to support the yuan and maintain the bank without any apparent change in the foreign asset position of the state banks, let alone the PBOC. And it seems that China’s state enterprises have foreign exchange liquidity buffers on their balance sheets (not those of the PBOC or the state) which also can be used for backdoor exchange rate management.

Mismatched Methodologies

None of these details are completely surprising. Few took Yi Gang’s statement that the PBOC had stopped intervening in the foreign exchange market as evidence that China has stopped managing its currency. Increased guidance of the state banks was widely reported back in the fall of 2022, when the yuan came under pressure ahead of the Party Congress.

It nonetheless raises important policy issues. China’s foreign currency management can no longer be assessed by looking at China’s reported foreign exchange reserves.

That’s a real problem for the U.S. Treasury, which hasn’t changed its basic methodology for evaluating countries’ currency management practices since 2016. Right now, the Treasury’s core approach is to avoid making any judgement about whether intervention at a given level of the exchange rate is appropriate, and rather to look at the scale and consistency of the country’s intervention in the market.

It goes without saying that this methodology only works if there is an accessible, accurate measure of actual direct and indirect intervention in the market. Right now, that isn’t the case for China. No one knows SAFE’s non-reserve dollar assets, the net foreign asset position of the two Chinese policy banks, or the forward book of China’s state commercial banks.

The IMF has even more work to do. Its global current account surveillance model – the one used for the external sector report – only looks at the change in a country’s formal reserves. The large balance sheet of China’s state banks, to my knowledge, has never entered the IMF’s analysis. Nor has the IMF examined the sources of foreign currency funding of the policy banks – which clearly include equity injections in foreign currency from SAFE and so-called entrusted loans.

To be sure, this is a long-term challenge, not an immediate problem.

China’s activities in the market have been designed to support the yuan (admittedly at a very weak level). Pushing the yuan up and trying to resist outflow pressure doesn’t give China an artificial competitive advantage – rather the contrary. China hasn’t allowed the market to push the yuan down.

But the broader issue remains: China’s tools for foreign exchange management are more advanced than the tools the rest of the world uses to analyze China’s rather opaque intervention.

To put it a bit more vividly, in the arms race between the tactics used for stealth intervention and the radar systems needed to detect it, China’s stealth technology currently has an edge. That needs to change.

Additional Background

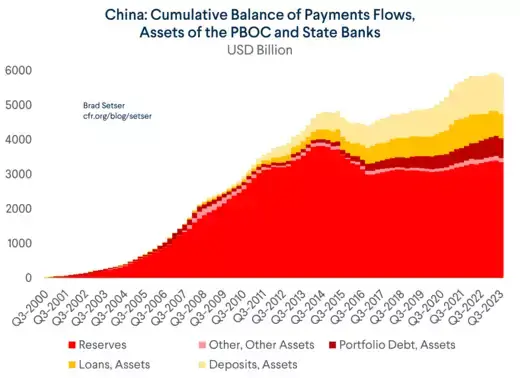

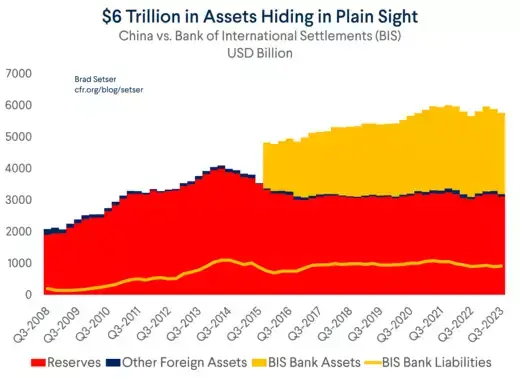

First, some have questioned my argument that China’s state has a lot of hidden foreign assets. But my argument really should not be controversial.

China itself discloses that the state banks have over $100 billion at the PBOC in foreign currency reserves that aren’t counted as part of the main body of foreign exchange reserves.

The China Investment Corporation (CIC) has a disclosed foreign portfolio of over $300 billion – $318 billion at the end of 2022, down from $370 billion the year before. This is also not really under any question; a lot of external fund managers are managing CIC money.

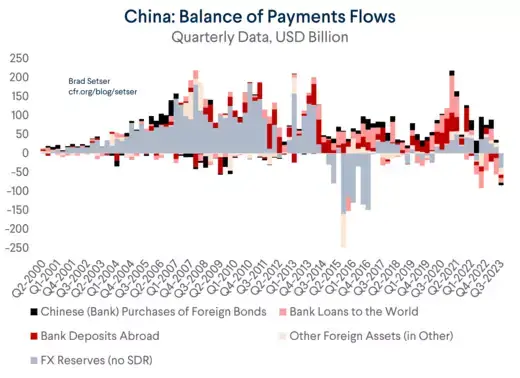

And the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) banking data, which groups like AidData use, shows a net foreign asset position of the state banking system of well over $1.5 trillion and gross foreign assets of more like $2.5 trillion.

That fits broadly with the numbers I have gotten by summing up flows in the balance of payments, which also clearly shows a buildup of assets in the state banking system.

The BIS numbers and the balance of payments numbers, in theory, include the policy banks. The sum should therefore be bigger than the $1 trillion net foreign asset position of the deposit-taking institutions.

Second, the IMF metric of reserve adequacy is sometimes used to suggest that China is under-reserved, as it has long showed that China is basically as under-reserved as Turkey and Argentina.

But the IMF metric itself is flawed: it ignores the net foreign asset position of the state banks, and it weighs domestic deposits (M2) far too heavily relative to reserves. It thus concludes that a country with a current account surplus and far more reported foreign exchange reserves than total external debt is under-reserved. And for countries like Turkey and Argentina, using gross reserves rather than net reserves (in other words, ignoring the central bank’s on- and off-balance sheet foreign currency liabilities) leads the metric to understate the country’s vulnerability.

* Another measure of China’s reserves is the change in reserves reported in the balance of payments, and there was a large unexplained fall in the third quarter. The balance of payments reserves measure was a near-perfect match with the PBOC balance sheet from 2005 to 2015 but has subsequently diverged for reasons that the PBOC has never disclosed – and which the IMF, to my knowledge, has never investigated.

** Because China doesn’t publish intervention numbers, the Treasury uses a broader set of indicators for China, including “foreign exchange settlement,” which historically has picked up changes in the net foreign asset position of the state commercial banks as well as changes in the foreign asset position of the PBOC. But this isn’t a systematic approach, and even for China, the Treasury does not use the balance of payments data for “other” (banks) as part of its process for evaluating whether a country has met the standard for being designated under either 1988 trade law or the 2015 Trade Enforcement Act.

*** The IMF’s recent Article IV reports on China have essentially ignored the balance of payments. The IMF has not, to my knowledge, examined changes in the foreign asset position of the state banks, nor changes in the flows through the banks reported in the balance of payments, in any thorough or systematic way. In 2022 and 2023, it took China’s stable reported reserves at face value. The issues around China’s growth outlook are important – as are measures of China’s true fiscal position – but that isn’t a good reason to forget that the IMF’s core mandate remains balance of payments surveillance.

**** For the mechanics on swaps, see my work with STW on Taiwan.

.png.webp.webp)