It is a given in polite economic society that China should move toward a more flexible exchange rate regime.

The IMF says so, and the U.S. Treasury has often echoed this point – though more recently, Treasury has wisely taken to emphasizing the need for greater transparency as much as the need for greater flexibility.

More on:

And Yi Gang – the former PBOC governor – has argued that China already has a flexible exchange rate. Back in the spring of 2023, he claimed China’s central bank had more or less stopped intervening in the foreign exchange market, stating that “in recent years, PBOC has by and large exited from regular intervention,” and thus China already had a managed float, if not a free float: “you can still call it a managed, floating regime, but [the yuan] has to be primarily determined by market.”

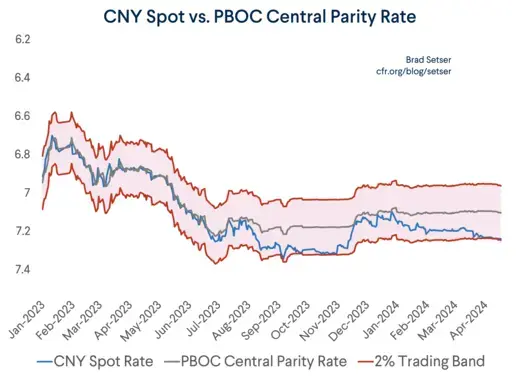

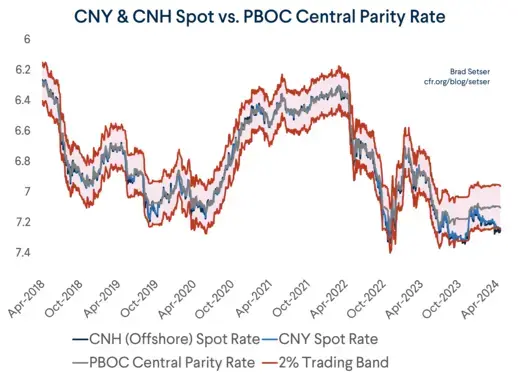

However, there is one obvious problem with characterizing China’s currency as managed float with a value that is primarily determined by the market: the yuan stopped even pretending to float sometime last year.

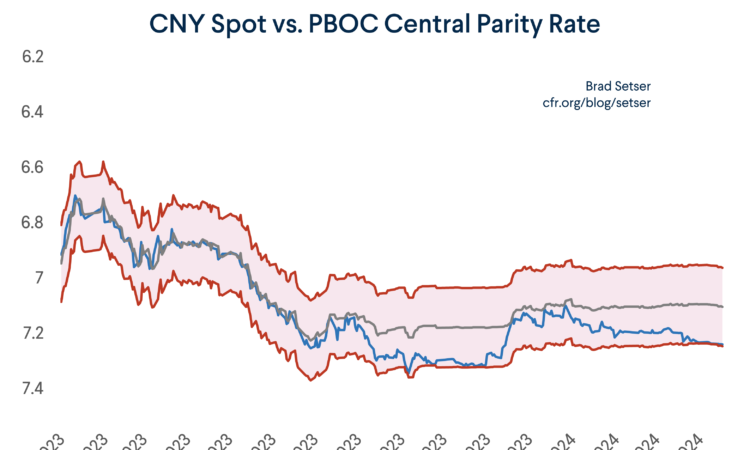

Faced with ongoing depreciation pressures (and a regime where, absent heavy-handed intervention by the PBOC, the market was basically leading the yuan to crawl down), the PBOC dropped the pretense that the yuan, which is required to trade within a two-percentage point band around the daily fix – was flexible and that the fix was somehow market determined. The fix just stopped moving, which meant that spot could weaken further.

It worked. The CNY has stabilized, and spot no longer leads the fix down. It just isn’t quite anything that can realistically be called a flexible exchange rate. It also has become clear that the PBOC is currently targeting the yuan’s value against the dollar, not its value against a basket of currencies.

Last fall, the yuan was basically pinned at 7.32 (spot) by a stable fix at about 7.17.

More on:

When the dollar depreciated a bit in December and early January on expectations that the Federal Reserve would be cutting interest rates this year, China was able to let the yuan appreciate a bit. The fix moved from 7.17 to around 7.1, and spot moved off the weak edge of the band.

But with the dollar strengthening a bit recently, the central point of the band has been stuck at 7.1 for a while now: the fix, so to speak, has been fixed.

And over the last two weeks, the yuan has moved to the weakest edge of the band.

Therefore, China’s options are:

- Return to what, for all intents and purposes, looks like a peg; currencies that trade in a band sometimes get stuck at one end of the range, which effectively results in a temporary peg.

- Intervene directly to move spot off the edge of the band (the PBOC knows how to push the currency around if it wants).

- Allow the band to reset to a lower level and reignite speculation about just how far China wants the yuan to fall.

This puts not only the PBOC in a bind, but also the U.S. and the IMF.

The standard exchange rate policy recommendation for China over the last fifteen years is that it needs to allow its exchange rate to be set by the market. That recommendation was the synthesis of two overlapping arguments which in the past were often in agreement, but now are in contention.

The first argument is that the frictions created by China’s integration into the global economy could be reduced if China’s institutions converged toward the norms of the large, advanced economies. The big economies (i.e., the U.S., the EU/euro area, Japan, the UK) have independent central banks that direct monetary policy toward stabilizing domestic conditions and rarely intervene in the foreign exchange market.

If China has a more market-driven exchange rate (and a more market driven economy), its ongoing integration with other large economies would thus be easier; the IMF argues that exchange rate flexibility would help China with monetary policy transmission.

The second argument was, in a sense, simpler: a market-driven exchange rate would be a stronger exchange rate, and a stronger yuan would result in a more balanced Chinese and global economy. Exchange rate flexibility was essentially just the agreed upon code for exchange rate appreciation – and exchange rate appreciation is the one policy adjustment that certainly does directly impact the trade balance (it clearly has a bigger impact than bilateral tariffs, for example).

The tension between those two points of view, of course, arises when letting the market set the exchange rate would mean a weaker exchange rate – and perhaps a much weaker exchange rate.

That is the case now. And when the two goals are in tension, I think considerations of external balance should win out – at least in China’s case.

China, after all, has run persistent and, at times, large current account surpluses throughout its period of high investment catch-up growth. That isn’t totally normal. Countries with unusually high levels of investment usually need to draw on global savings to finance all their building and draw on global supply to complete their investment projects.

China has been a persistent outlier here, combining unusually high levels of investment with even higher domestic savings rates and an ongoing surplus.

Moreover, that surplus – the goods surplus at least, as the current account number has stopped tracking the goods balance for rather mysterious reasons recently – has soared over the last four years.

The rest of the world responded to the pandemic by sending out checks to help keep household spending up during the lockdowns; China responded to the pandemic by revving up its factory floors to meet increased demand for goods – and by consciously not providing much fiscal support for demand.

China’s surplus in goods – and in manufactured goods – both basically doubled (in dollar terms) between 2019 and 2023.

And China’s manufacturing surplus – at 10 percent of China’s considerable GDP – is now extremely large relative to the output of its trading partners. Indeed, at around 2 percent of World GDP, China’s manufacturing surplus is the already the biggest in post-war economic history by the same measure.

Thanks to a significant real depreciation over the last two years, China’s export volumes are already outpacing global trade growth.

Put simply, China’s existing surplus is so big that it should raise concerns about any policy path that aims to help China return to internal balance through larger external imbalances.*

The last thing a world already struggling with the impact of China’s growing capacity to produce green goods (and its growing exports of dirty goods like steel as its own economy slows) needs is for a weaker yuan to add even more support to China’s export engine. U.S. Treasury Secretary Yellen got this right: “China is too large to export its way to rapid growth,” Yellen said an event hosted by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, adding that the nation’s factories are currently churning out more than “the global market can bear.”

China needs to look for policies that move it closer toward book internal and external balance – and that (uncomfortably) means limiting the use of classic monetary policy tools.

But it is also reasonable that China made a real effort to use its domestic policy space to support its own recovery—and so far it has not been willing to provide direct support to lower income households, or to consider reforms to its exceptionally regressive tax system. Logan Wright and Daniel Rosen foot stomped these points in a recent article in Foreign Affairs.

Ultimately, of course, China sets its own exchange rate policy; it has a long history of ignoring external advice that goes against its self-perception of its own interests. But there is no reason why China’s trade partners should encourage China to move toward more flexibility right now, when it would only help China export more of its own manufactures to a reluctant world. Pragmatism should rule.

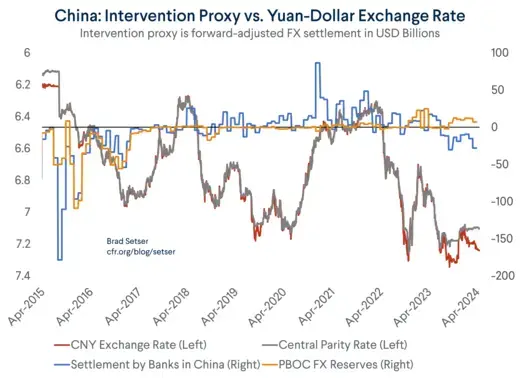

There is, of course, another issues around China’s currency right now. Namely, the question of how China manages to keep it stable without much obvious intervention.

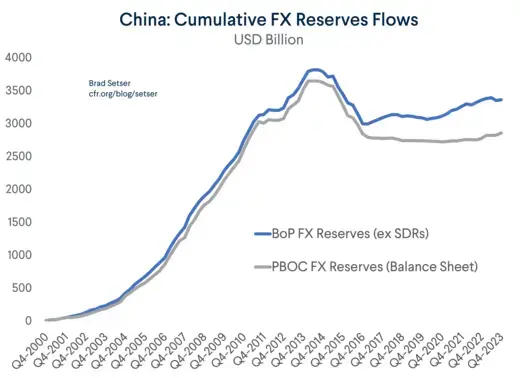

There isn’t actually a clear answer because relevant Chinese data is at odds with itself. Take the PBOC’s balance sheet data, for example.

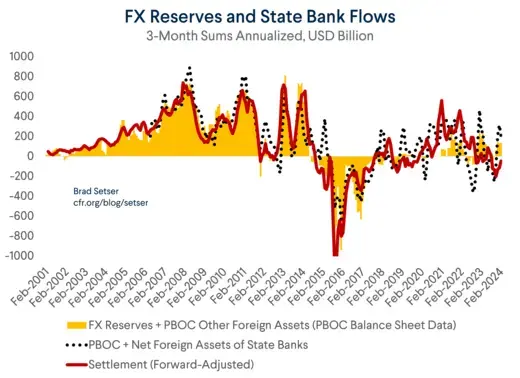

After years of surprising stability, the PBOC has consistently reported adding around $10 billion a month to its foreign exchange reserves (gold line in the chart)

That is strange, as the PBOC never reported adding a thing to its reserves back in 2020 and 2021 when the yuan’s strength suggested that the PBOC should be buying. And the current purchases come when other indicators suggest the PBOC should be selling to limit yuan weakness and keep the yuan inside the plus/minus two percent band around the daily fix. Frankly, it is so strange that it warrants some form of explanation.

The balance of payments data is also strange. The balance of payments data showed significant ($43 billion) reserve sales in the third quarter of 2023, but $11 billion in reserve purchases in the fourth quarter – for the year, reserves were flat, after a roughly $100 billion increase in reserves in 2022 (when the PBOC balance sheet was flat and the PBOC supposedly transferred $120 billion to the budget through a special dividend … hmmm).

It is all a bit odd, but the balance of payments reserves numbers haven’t lined up with the PBOC’s balance sheet since 2016 – a statistical quirk that really shouldn’t go without investigation from the IMF.

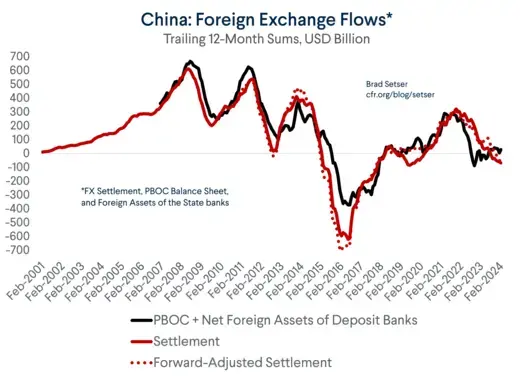

Also consider the settlement data (blue line in the chart above). Settlement combines data from the PBOC and the state banking system. It has consistently shown (modest sales) over the last few months. If the PBOC is really adding to its reserves, the sales in settlement imply ongoing sales from the state banks.

That certainly matches the anecdotes reported by the press, but it doesn’t fully match the reported numbers on the state banks’ foreign asset position. In the twelve months through February, settlement data shows sales of around $100 billion – with the PBOC balance sheet showing an increase of $50 billion or so, there should be a $150 billion fall in the net foreign asset position in the state banks.

But the state banking system data doesn’t show such a fall.

And the gap has been particularly pronounced in the last few months.

The common denominator – apart from the technical difficulties getting series that should line up to actually line up – is that none of the indicators show a large swing in the net foreign asset position of the Chinese state. For now, the outflow pressure appears manageable, and depreciation would thus be a policy choice.

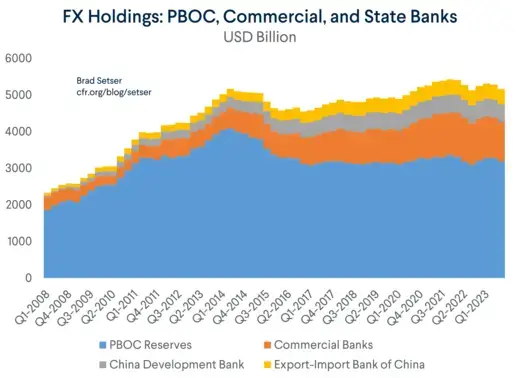

Let’s step back a bit and define the foreign assets of the Chinese state a bit more carefully. China’s main reserve manager, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), is part of the PBOC – and the PBOC reports to China’s State Council (and of course is subject to Party control as well). But the PBOC is hardly the only institution in China that has a large foreign asset position and reports to State Council.

China’s main sovereign wealth funds, the Chinese Investment Corporation (CIC), also reports directly to the State Council – and technically also is a holding company that owns the big state commercial banks.

The PBOC, through a subsidiary capitalized out of nearly $100 billion of SAFE’s reserves back in 2014, and the CIC notionally own China’s main policy banks: the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim) and the China Development Bank (CDB). In practice, though, the China Development Bank and Exim report directly to the State Council. China’s export credit insurer (Sinosure) is also owned by the CIC – it is all a bit incestuous.

Consequently, one reasonable definition of the foreign assets of China’s central government (what might be called China’s reserves and its shadow reserves) is the combined foreign holdings of all these big centrally owned institutions.

The PBOC’s formal reserves can be taken directly from China’s own reporting. The CIC is a bit harder, but it reports on its financial portfolio annually. The PBOC also reports the foreign assets of the deposit taking financial institutions monthly – and most of those assets are held by the five large national state commercial banks.

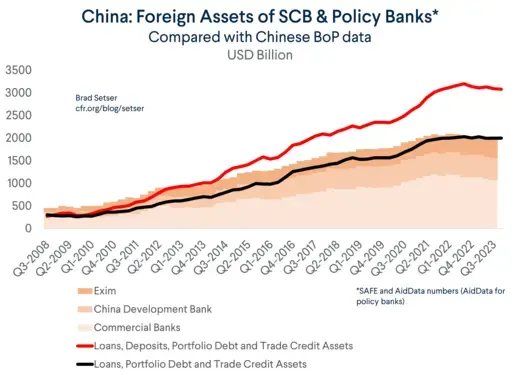

The main reporting gap comes from the lack of disclosure from the non-deposit taking (bond-financed) policy banks. Exim and the CDB account for the majority of China’s Belt and Road lending and clearly have been central to the “diversified use” of China’s foreign exchange reserves.**

But it is possible to take the numbers that the hard-working sleuths at AidData have found (by carefully counting disclosures from China’s borrowers) to construct a data series showing the external lending of the policy banks over time. Guess what: it generally lines up and helps fill in the gap between the state commercial banking data and the numbers reported to the Bank of International Settlements (and in the balance of payments). If anything, the AidData numbers are smaller than what is needed to really fill the gap.

Point being, China has a lot of foreign assets, seen and unseen. And those numbers don’t really suggest that China’s de facto repeg is under stress.

And the bigger point is that China guards its secrets closely, and no longer wants outsiders to be able to easily track its intervention.*** That, though, should be taken as a challenge by both the IMF and the U.S. Treasury.

* Sorry, IMF – the last Article IV totally ignored external balance. The emphasis was entirely on the need for fiscal consolidation (even if the IMF wanted China to wait a year to get started), interest rate cuts (price based monetary policy transmission), and more flexibility in the exchange rate to fight disinflation. Any standard macroeconomic model would suggest these recommendations, if adopted, would lead to a large surge in China’s external surplus. China’s problems of internal balance would be solved by adding to China’s external imbalances… at a time when both the U.S. and Europe are concerned about the external spillovers from China’s demand weakness.

** Check out Box 6 of SAFE’s annual report for 2020. It is a Rosetta Stone of sorts.

*** Sadly, the PBOC seems to have convinced the IMF not to look closely at these issues, despite the IMF’s mandate for balance of payments surveillance. Nothing in the 2023 IMF surveillance report suggests that the IMF understands that there is a real issue here, let alone that it has cracked the code. There is no (as in zero, zilch, nada) analysis of the role of the state banks in China’s foreign exchange management. I benefit from the lack of competition here, but would welcome a more serious investigation of this issue by the Fund – or if it is too hot for the Fund, from the G-7.