Peter Bofinger argues that introducing central-bank

digital currencies would need to be subject to very careful consideration.

While Facebook’s Libra

is confronted

by ever stronger headwinds, a new competitor, the so-called central-bank

digital currency (CBDC), is entering the arena of digital money. While this

idea has been discussed by several central banks for some time now, it has been

boosted by recent announcements by Chinese central bankers. On August 10th Mu

Changchun, deputy chief of the payment and settlement division of the People’s

Bank of China, said:

‘People’s Bank digital currency can now be said to be ready.’

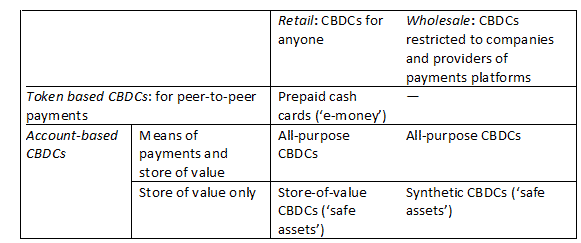

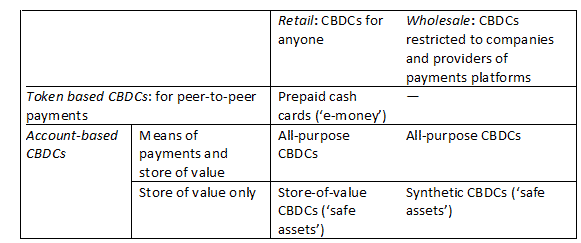

Different types of CBDC

have been mooted (see table). Account-based

CBDCs would make it possible for private households and corporations

to open an account with the central bank. This could be designed as an

all-purpose account for anyone, with unlimited uses (retail CBDCs). But CBDCs could

also be designed as a pure store of

value, which would only allow transactions between the central-bank

account and a designated traditional bank account. Such accounts could be

organised as retail CBDCs but access could be restricted to large investors and

providers of payments platforms (wholesale CBDCs).

Token-based CBDCs (‘digital cash’) are imagined as an alternative

to cash for peer-to-peer transactions. They could be designed as prepaid cash cards

issued by the central bank, without the user having an account with the central

bank.

A typology of CBDCs

These CBDC variants

challenge existing money, financial-assets and payments providers:

- Token-based

CBDCs would compete above all with private providers of digital-payments

products (such as credit-card companies, Paypal and Alipay). - All-purpose

CBDCs would compete with traditional bank accounts. - Store-of

value, account-based CBDCs would compete with time deposits of commercial banks

but particularly with ‘safe assets’ and above all government bonds.

With the issuance of

token-based CBDCs, but also with all-purpose CBDCs for anybody, central banks would

compete with private suppliers of payments networks and commercial banks.

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

Such a change in the

competitive environment could only be justified were a significant market

failure to be identified. The Swedish Rijksbank argues:

‘If the state, via the central bank, does not have any payment services to

offer as an alternative to the strongly concentrated private payment market, it

may lead to a decline in competitiveness and a less stable payment system, as

well as make it difficult for certain groups to make payments.’

Effective

competition policy

But the solution to

these problems is not necessarily that the central bank becomes a provider of retail-payments

services. Rather, this calls for an effective competition policy and comprehensive

supervision of payments providers. And one has to ask whether the central bank

would be an adequate institution for screening, monitoring and supporting

customers, as well as developing new retail-payment technologies.

In addition, all-purpose

CBDCs for private households and companies could raise serious problems for the

financial-intermediation mechanism.

If bank customers decided to shift significant parts of their deposits to the

central bank, the deposit base of commercial banks would be reduced. This gap would

have to be filled by the central bank, which would in turn require sufficient

eligible collateral on the part of the banks.

If such accounts were

to gain in popularity, the central bank would increasingly find itself in a situation

in which it would have to refinance private loans and decide, indirectly or

directly, on the quality of private borrowers. In the end a ‘full money’ (or 100

per cent reserve) financial system could emerge, in which commercial banks

would lose the ability to create credit independently. Contrary to its advocates,

this would massively throttle or even eliminate a central driver of economic

momentum.

Safe assets

While fully-fledged CBDCs

for private households and firms would be associated with serious challenges

and risks for the whole financial system, there are no obvious market failures which

could warrant such innovation. This raises the question of whether the

introduction of CBDCs should be limited to ‘store of value’ CBDCs (sov-CBDCs).

Such central-bank balances could not be used for payments to third parties but

only for transfer to one’s own account at a commercial bank.

With store-of-value

CBDCs the central bank would not compete with payments providers. The

competition with commercial banks would be limited to short-term time and

saving deposits, without depriving banks of their liquid deposit base. Above

all, such CBDCs would provide a safe asset, which in this form could not be

created by private actors. Sov-CBDCs would be comparable to cash as they would

provide a 100 per cent guarantee of nominal value, which cannot be guaranteed by

bank accounts—according to the Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive, depositors

with assets in excess of €100,000 must be bailed in if their bank gets into

trouble—or government bonds.

The attractiveness of

this asset would be largely determined by its rate of return. Treating it as a digital

substitute for cash, a zero interest rate would be appropriate. In this case,

the substitution processes from traditional bank deposits to CBDCs would be

limited. In addition, a lower limit of €100,000 for sov-CBDCs could be

justified, as bank customers with lower deposits are protected by national

deposit-insurance schemes.

Overall, such CBDCs would

increase the stock of ‘safe assets’ that are of great importance to the players

in the financial markets. This is also not without risks, however, as the

introduction of a new safe asset could be detrimental for countries with a

poorer bond rating. Moreover, in periods of crisis such CBDCs could lead to

digital bank-runs, which would further destabilise the system.

Synthetic CBDCs

The narrowest version

of CBDCs comprise store-of-value CBDCs restricted to providers of payments

services as a collateral for their depositors (‘stable coins’). The designers

of Libra plan to use bank deposits and government bonds as collateral. But, as indicated,

the stability of bank deposits in a crisis is limited. As for government bonds,

massive sales by Libra would likely result in price losses. These problems

could be avoided if suppliers of stable coins could use CBDCs as collateral. Adrian

and Manicini-Griffoli speak

of synthetic CBDCs (sCBDCS).This model is

already being practised in China, where Alipay is obliged to keep its accounts

with the central bank.

In principle, this

could result in ‘narrow banks’, which on their asset side only maintained

balances with the central bank and concentrated on the function of payment-service

provider. These would be opposed by ‘investment banks’, operating the

traditional credit business and offering longer-term, interest-bearing

deposits. Compared with all-purpose CBDCs, this arrangement has the advantage

that the payments system is operated by private suppliers and not by the

central bank. But there is also the risk that the banking system loses the

ability to generate loans and a full-money financial system develops.

The introduction of

CBDCs, in whatever form, should be subject to very careful consideration. There

is little to suggest today that central banks should play an active role as

payment-service providers, as would be the case with the introduction of token

CBCDs and all-purpose central-bank deposits. Not least, there would be the

danger that this would be used by states to achieve even closer monitoring of

their citizens.

An interesting innovation, however, would be if CBDCs could only be used as a store of value. Such an asset could only be created by the central bank and it would be particularly interesting for companies and investors who would be confronted with a bail-in in the event of a bank insolvency. Such CBDCs could serve as collateral for payment-service providers issuing a stable coin. But since this could lead to considerable changes in the way the entire financial system functions, no hasty steps should be taken here either.

This article is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal