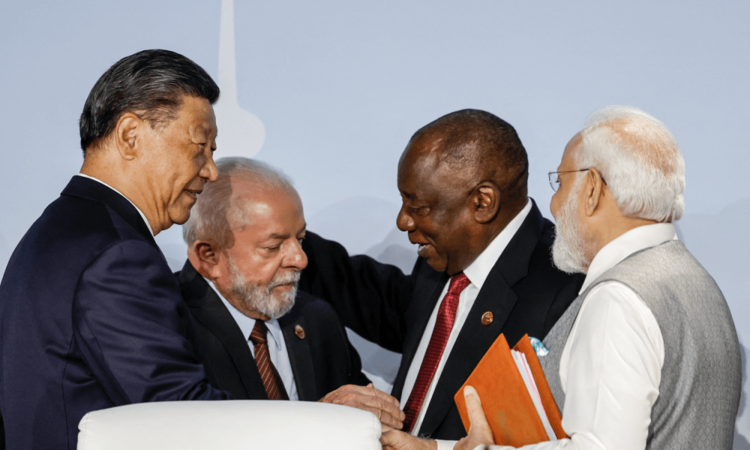

In the months before August’s gathering of BRICS leaders in South Africa, rumors of a new BRICS currency swirled—only to fail to manifest at the summit itself. But don’t confuse a single summit’s headlines with evidence of a trend.

The wake of the BRICS summit splashes into a world much riper for de-dollarization now than it was even six months ago. BRICS, now BRICS+ due to the admission of new members, deserves only partial credit. In the last six months, tectonic shifts in China’s economy and in Washington have cleared the path for de-dollarization—an open route that BRICS+ can now step into.

BRICS+ may bring the global south’s economic statecraft from the 20th to the 21st century. In the 20th century, non-Western economic blocs, such as OPEC, gained geopolitical power through their control over the supply of specific economic commodities, such as oil. In the 21st century, non-Western economic blocs, such as BRICS+, can gain influence over the West through several economic channels at once. Twentieth-century oil embargoes may seem passe, even puny, relative to the 21st-century trade and financial actions that BRICS+ could theoretically now manage.

You can preview these new tools of economic statecraft in the composition of the admitted members who expanded the bloc from BRICS to BRICS+.

With Egypt, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia, BRICS+ can disrupt world trade not just in oil, but in everything. These three countries encircle the Suez Canal and effectively turn it into a BRICS+ lake. The canal is a key artery of the world economy. Some 12 percent of all global trade runs through the canal, which runs from the Mediterranean into the Red Sea. And it is the Red Sea that BRICS+ now encircles. Embanked by Egypt on the west and Saudi Arabia to the east, the Red Sea may not have beaches in landlocked Ethiopia, but Ethiopia is a regional power in East Africa. It has influence over the other East African countries, like Sudan and Somalia, that fill out the rest of the Red Sea’s western shore. If you wanted to weaponize the Suez’s importance in global trade, you’d have admitted Egypt, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia. BRICS admitted Egypt, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia.

The admission of Saudi Arabia also broadens the economic leverage at the disposal of BRICS+ in financial holdings. Saudi Arabia owns more than $100 billion in U.S. government bonds. BRICS+ countries now own more than $1 trillion in Uncle Sam’s bonds by a comfortable margin. And the amount of U.S. government holdings understates the influence that Saudi Arabia’s money grants it over the U.S. and Europe. The Saudis turn money into geopolitical power by buying influential private organizations such as “the entire sport of professional golf,” a recent purchase of Riyadh’s.

The new membership of BRICS+ also represents a range of commodities that offers a spectrum of power both now and in the future. Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—among the new BRICS+ members—are also fossil fuel exporters. Meanwhile, countries such as Brazil, China, and Russia are significant producers of the metals and rare earths that the energy transition will depend on.

The history of OPEC is a story of cooperation on issues of shared economic interests between even countries literally at war with each other. In the 1980s, through OPEC, Iran and Iraq cooperated on setting oil prices even while each targeted the other side’s oil production facilities, including tankers at sea, and killed hundreds of thousands of its people. There are understandable doubts that countries like China and India can cooperate on issues of shared interest because of areas of conflict on other issues, like their shared border.

But if Iran and Iraq could cooperate on shared economic interests within OPEC in the 20th century as a war that included “some of the most brutal conventional warfare in modern history” raged on their shared border, in the 21st century, China and India can cooperate within BRICS+ to advance shared economic interests even as skirmishes fought with clubs instead of guns erupt along their shared border.

If OPEC was powerful in the 20th century, BRICS+ is now set to be more than a little more powerful in the 21st century. But for the prospects of de-dollarization, the story gets even better. Any BRICS+ push toward de-dollarization will benefit from developments in Beijing and Washington that have little to do with BRICS or BRICS+.

A case for skepticism about the efficacy of some version of BRICS moving the ball forward on de-dollarizing, or much of anything, once came from the relative enormity of China’s economy. After all, China’s economy is 2.3 times the size of the rest of the original BRICS and 1.7 times the rest of BRICS+ in terms of GDP. That gives other countries grounds to fear BRICS could just be a new chance for China to treat other developing countries as its subordinates. With China’s rate of economic growth slowing to the point that it may even be shrinking, however, that changes. A smaller Chinese economy means a more balanced BRICS. And a more balanced BRICS is one that more believably serves shared interests rather than those of a domineering China. That’s a gift to BRICS+.

Meanwhile, in Washington, skepticism about how closely dollar hegemony matches U.S. national interests is growing. In June, the U.S. Senate confirmed a man who views dethroning the dollar as good for the United States as the chairman of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers. That could make Joe Biden’s White House the second in a row to see skepticism about the benefits of dollar hegemony reach the Oval Office.

Breaking tradition with past U.S. presidents, Donald Trump touted the benefits of a weak dollar as a means of reducing the trade deficit. That matters for de-dollarization’s outlook. If official Washington regards preserving the dollar’s role in the global economy as a vital U.S. national interest, it could threaten to impose the type of penalties, like financial sanctions or even military action, on countries that took steps towards de-dollarization. If it does, that could plausibly prevent de-dollarization from actually happening. If it won’t, then one more roadblock in de-dollarization’s path crumbles, clearing the way for BRICS+ to continue down the path.

At the summit, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva also announced a working group to study a “reference currency” for a common BRICS+ trade currency. That means BRICS+ is working on the rational next step toward a shared trade currency. A reference currency, broadly speaking, refers to a way of coordinating how the national currencies of BRICS+ members convert into the shared trade currency. A reference currency could be a defined basket of national currencies, like the International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights.

Once that basket is defined, the exchange rate between the national currency and the shared trade currency becomes a function of the market price of one national currency relative to the others in the basket. Another way of establishing a reference currency would be to link the shared trade currency’s price to a quantity, say an ounce, of a commodity, such as gold. In that case, gold serves as the reference currency. The price of gold in terms of the national currency then determines how much national currency you need to buy the shared trade currency. Either approach is possible, as are others. The working group will need to hammer out those details.

If BRICS+ prioritize dethroning the dollar more than many suspect, you’d expect it to surprise the world, as it did, with a role for Argentina. That’s because it is hard to imagine Argentina looking like a globally attractive economic partner unless you’re really into the de-dollarization of trade. Its economy isn’t even growing. Its history of hyperinflation is so bad that its economists become national celebrities. But one thing that Argentina does have is an agreement with Brazil to, in bilateral trade, replace dollars with what amounts to a new currency.

The BRICS+ nations do not need to wait until a shared trade currency meets the technical conditions typical of a global reserve currency before they swing their newly enlarged economic wrecking ball at the dollar. These conditions include things like a currency’s use in trade by parties from third countries, like the yuan in its budding use for trade between Russia and countries besides China. But those technical conditions are of greater interest to Western wonks than BRICS+ governments. And dominant currencies get no exemption from the principle that it is easier to destroy than create. If BRICS+ does roll out a shared currency, in all probability, it’d almost certainly be doing so before Western economists say it’s ready. But that does not mean that it wouldn’t do it.

The BRICS+ states do not even necessarily need to have a shared trade currency to chip away at King Dollar’s domain. If BRICS+ demanded that you pay each member in its own national currency in order to trade with any of them, the dollar’s role in the world economy would go down. There would not be a clear replacement for the dollar as a global reserve. A variety of currencies would gain in importance.

That could put the U.S. dollar in a position like the British pound in the 19th century. Asked to identify a single national currency as the global reserve of the era, commentators tend to name the pound. When today’s economists construct measures of “monetary system dominance,” however, for decadelong stretches of the 19th century, Britain never surpasses 50 percent.

That was also true of the pound in its waning days as a global reserve in the early 20th century: It never surpassed 50 percent of official foreign exchange reserves. If the dollar came to retain a plurality but not majority of reserves, some would say it retained its reserve status. But that’d be a change. Even if King Dollar technically remained on the throne, it’d herald a new era of rising monetary anarchy under his watch.

If King Dollar could speak to those who expected BRICS to announce its slaying at the August summit, it might use a popular saying: The rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated. That may have been true this time. Rumors of the dollar’s death were exaggerated in the buildup to the August BRICS summit. In the time since, though, conditions in Washington and Beijing appear to be conspiring to make the dollar’s vulnerability to BRICS+ greater than it was even six months before.

If the dollar died, then, it may end up like Mark Twain, who originated the saying with his response to a premature publication of his obituary in 1897. When the rumor circulated a second time, in 1910, Twain really had died. Rumors of the death of the dollar as a global reserve may have been exaggerated in the leadup to August’s summit. This time around, however, the rumors of its death may be no exaggeration.