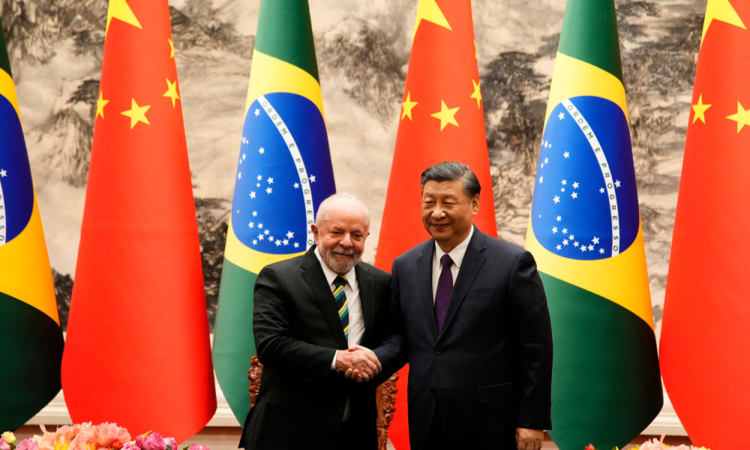

Talk of de-dollarization is in the air. Last month, in New Delhi, Alexander Babakov, deputy chairman of Russia’s State Duma, said that Russia is now spearheading the development of a new currency. It is to be used for cross-border trade by the BRICS nations: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Weeks later, in Beijing, Brazil’s president, Luiz Inàcio Lula da Silva, chimed in. “Every night,” he said, he asks himself “why all countries have to base their trade on the dollar.”

Talk of de-dollarization is in the air. Last month, in New Delhi, Alexander Babakov, deputy chairman of Russia’s State Duma, said that Russia is now spearheading the development of a new currency. It is to be used for cross-border trade by the BRICS nations: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Weeks later, in Beijing, Brazil’s president, Luiz Inàcio Lula da Silva, chimed in. “Every night,” he said, he asks himself “why all countries have to base their trade on the dollar.”

These developments complicate the narrative that the dollar’s reign is stable because it is the one-eyed money in a land of blind individual competitors like the euro, yen, and yuan. As one economist put it, “Europe is a museum, Japan is a nursing home, and China is a jail.” He’s not wrong. But a BRICS-issued currency would be different. It’d be like a new union of up-and-coming discontents who, on the scale of GDP, now collectively outweigh not only the reigning hegemon, the United States, but the entire G-7 weight class put together.

Foreign governments wanting to liberate themselves from reliance on the U.S. dollar are anything but new. Murmurs in foreign capitals about a desire to dethrone the dollar have been making headlines since the 1960s. But the talk has yet to turn into results. By one measure, the dollar is now used in 84.3 percent of cross-border trade—compared to just 4.5 percent for the Chinese yuan. And the Kremlin’s habitual use of lies as an instrument of statecraft offers grounds for skepticism about anything Russia says. On a litany of practical questions, like how much the other BRICS nations are on board with Babakov’s proposal, for now, answers remain unclear.

Nevertheless, at least based on the economics, a BRICS-issued currency’s prospects for success are new. However early plans for it are, and however many practical questions remain unanswered, such a currency really could dislodge the U.S. dollar as the reserve currency of BRICS members. Unlike competitors proposed in the past, like a digital yuan, this hypothetical currency actually has the potential to usurp, or at least shake, the dollar’s place on the throne.

Let’s call the hypothetical currency the bric.

If the BRICS used only the bric for international trade, they would remove an impediment that now thwarts their efforts to escape dollar hegemony. Those efforts now often take the form of bilateral agreements to denominate trade in non-dollar currencies, like the yuan, now the main currency of trade between China and Russa. The impediment? Russia is unwilling to source the rest of its imports from China. So after bilateral transactions between the two countries, Russia tends to want to park the proceeds in dollar-denominated assets to buy the rest of its imports from the rest of the world, which still uses the dollar for trade,.

If China and Russia each used only the bric for trade, however, Russia would not have any need to park the proceeds of bilateral trade in dollars. After all, Russia would be using brics, not dollars, to buy the rest of its imports. Enter, at last, de-dollarization.

Is it realistic to imagine the BRICS using only the bric for trade? Yes.

For starters, they could fund the entirety of their import bills by themselves. In 2022, as a whole, the BRICS ran a trade surplus, also known as a balance of payments surplus, of $387 billion – mostly thanks to China.

The BRICS would also be poised to achieve a level of self-sufficiency in international trade that has eluded the world’s other currency unions. Because a BRICS currency union—unlike any before it—would not be among countries united by shared territorial borders, its members would likely be able to produce a wider range of goods than any existing monetary union. An artifact of geographic diversity, that is an opening for a degree of self-sufficiency that has painfully eluded currency unions defined by geographic concentration, like the Eurozone, also home to a $476 billion trade deficit in 2022.

But the BRICS would not even need to trade only with each other. Because each member of the BRICS grouping is an economic heavyweight in its own region, countries around the world would likely be willing to do business in the bric. If Thailand felt compelled to use the bric to do business with China, Brazil’s importers could still purchase shrimp from Thai exporters, keeping Thailand’s shrimp on Brazil’s menus. Goods produced in one country can also circumvent trade restrictions between two countries by being exported to, and then re-exported from, a third country. That’s often a consequence of new trade restrictions, like tariffs. If the United States boycotted bilateral trade with China rather than trade in the bric, its children could continue to play with Chinese-made toys that became exports to countries like Vietnam and then exports to the United States.

A preview of something like the absolute worst-case scenario that could befall consumers in BRICS countries if their governments adopted “bric or bust” terms of trade comes from today’s Russia. American and European governments have prioritized Russia’s economic isolation. Nevertheless, some U.S. and European goods continue to flow into Russia. The costs for consumers are real, but not catastrophic. As officials in BRICS countries grow increasingly emphatic about their desire to de-dollarize, with today’s Russia as an upper bound of how bad it could get, the risk-reward tradeoff of de-dollarization will look increasingly attractive.

To displace the dollar as a reserve currency among BRICS, the bric would also need safe assets to be parked in when not in use for trade. Is it realistic to imagine the bric finding these? Yes.

For starters, because the BRICS run a trade and balance of payments surplus, the bric would not necessarily need to attract any foreign money at all. BRICS governments could use some combination of carrots and sticks to get their own households and firms to buy bric assets with their savings and effectively coerce and subsidize the market into existence.

But assets denominated in the bric would actually have characteristics likely to make them unusually attractive to foreign investors. Among the major drawbacks of gold as an asset class for global investors is that, in spite of its risk-reducing value as a diversifier, it does not pay interest. Since the BRICS reportedly plan to back their new currency with gold and other metals with intrinsic value, like rare-earth metals, interest-paying assets denominated in the bric would resemble interest-paying gold. That’s an unusual characteristic. It is one that could make the assets denominated in the bric attractive to investors who want both the interest-bearing property of bonds and the diversifying properties of gold.

Sure, for bric bonds to simply function as an interest-bearing version of gold, they’d need to be perceived as having a relatively low risk of default. And the debt even of sovereign governments in the BRIC countries has non-trivial default risk. But these risks could be mitigated. Issuers of debt denominated in the bric could shorten debt maturities to lower the riskiness. Investors might trust a government in South Africa to pay you back “30 from now” when the unit of time is days but not when it is years. Prices could also simply compensate investors for that risk. If market participants demanded higher yields for buying bric assets, they could likely get them. That’s because BRICS governments would be willing to pay for the viability of the bric.

The bric, to be fair, would raise a litany of thorny practical concerns. Used primarily for international trade rather than domestic circulation within any one country, the bric would complicate the job of national central bankers in BRICS countries. Creating a supranational central bank like the European Central Bank to manage the bric would also take work. These are challenges—but not necessarily insurmountable ones.

The geopolitics among BRICS members is also thorny. But a BRICS currency would represent cooperation in a well-defined area where interests align. Countries like India and China may have security interests at odds with each other. But India and China do share an interest in de-dollarizing. And they can cooperate on shared interests while competing on others.

The bric would not so much snatch the crown off of the dollar’s head as shrink the size of the territory in its domain. Even if the BRICS de-dollarized, much of the world would still use dollars, and the global monetary order would become more multipolar than unipolar.

Many Americans are inclined to lament declines in the dollar’s global role. They should think before they lament. The dollar’s global role has always been a double-edged sword for the United States. Though it does allow Washington to add sanctions to its foreign-policy toolkit, by raising the price of the U.S. dollar, it raises the cost of American goods and services to the rest of the world, decreasing exports and costing the United States jobs. But the side that cuts into America at home has been sharpening, and the side that cuts America’s enemies abroad has been dulling.

Among those who understand that the dollar’s global role comes at the expense of jobs and export competitiveness at home, at least based on comments from 2014, is Jared Bernstein, now head of the White House Council of Economic Advisors. But these costs have only grown over time as the U.S. economy shrinks relative to the world’s. Meanwhile, among the traditional benefits of the dollar’s global role is America’s ability to use financial sanctions to try to advance its security interests. But Washington sees the security interests of the United States in the 21st century as increasingly defined by competition with state actors like China and Russia. If that is correct, and if the checkered track record of sanctions on Russia is any indication, sanctions will become an increasingly ineffective tool of U.S. security policy.

If the bric replaces the dollar as the reserve currency of the BRICS, the reactions will be varied and bizarre. Applause seems poised to come loudly from officials in BRICS countries with anti-imperialist dispositions, from certain Republicans in the U.S. Senate, and from U.S. President Joe Biden’s top economist. Boos seem poised to emanate from both former U.S. President Donald Trump and the U.S. national security community that he so often feuds with. Either way, the dollar’s reign isn’t likely to end overnight—but a bric would begin the slow erosion of its dominance.