As Hong Kong’s currency peg marks 40th birthday with little fuss, some traders dither over its future

“For any monetary system, that is the trade-off,” Yue said. “If we want our interest rate policy back, then you forgo exchange rate stability.”

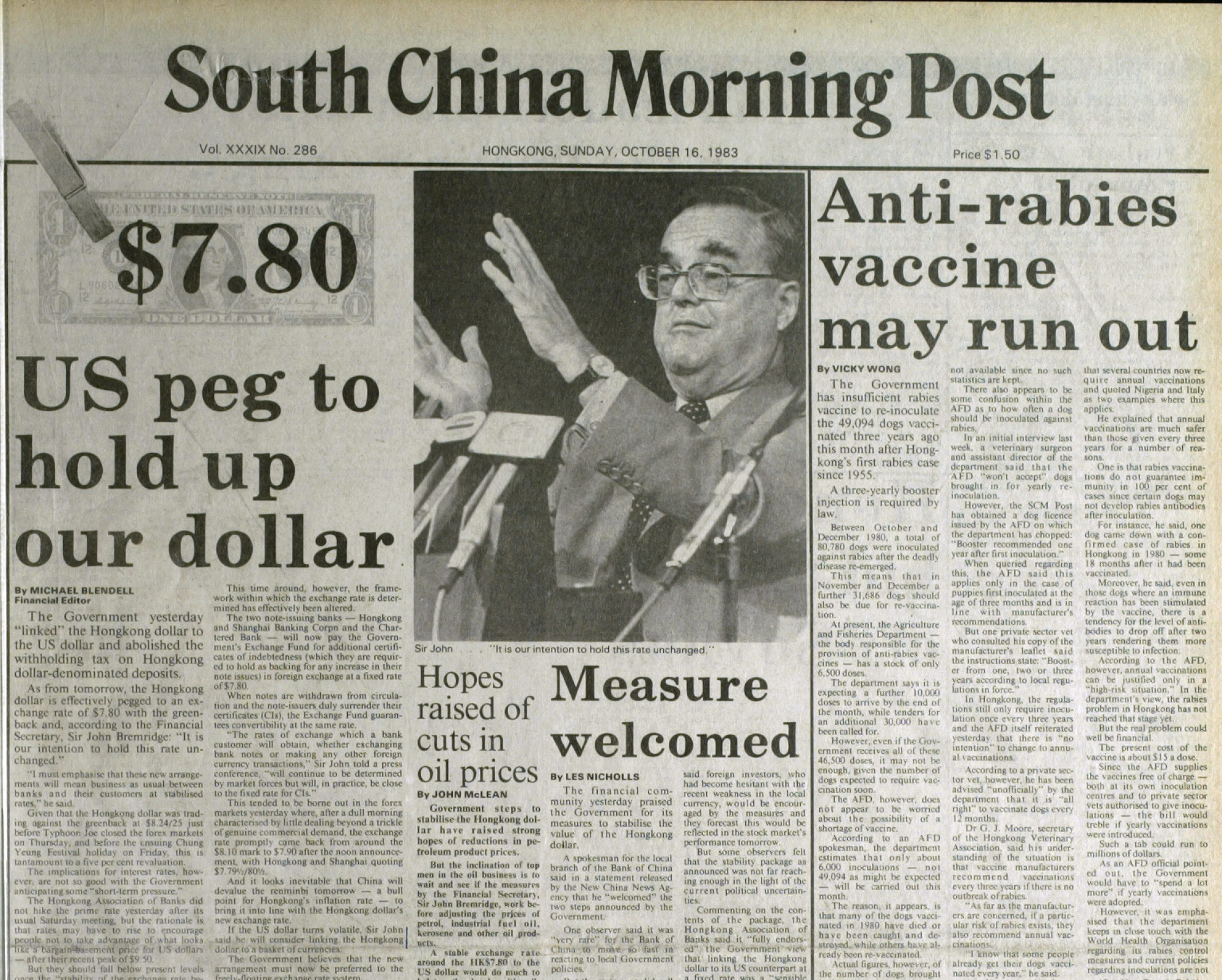

“Back then, I was a money and currency trader at Citibank, and I clearly remembered the Saturday morning when the Reuters machine suddenly flashed the breaking news that the Hong Kong dollar was to be fixed at 7.8 per US dollar” with effect from October 17, 1983, he said, recalling the initial announcement.

“We in the dealing room were shocked, and nobody knew how to react to the government’s move to scrap the floating rate and announce a US dollar-pegged regime without warning,” said Chan, who is now an adviser to a local banking group. “It was chaotic in the dealing room” the following Monday, he added.

Until that peg, the Hong Kong dollar had gone through several system changes. The currency was linked to the value of silver and to the British pound in the early part of the last century. It was allowed to float freely in 1974 when wild swings and a crisis of confidence gripped the markets amid efforts linked to the 1997 handover of Hong Kong back to Chinese sovereignty.

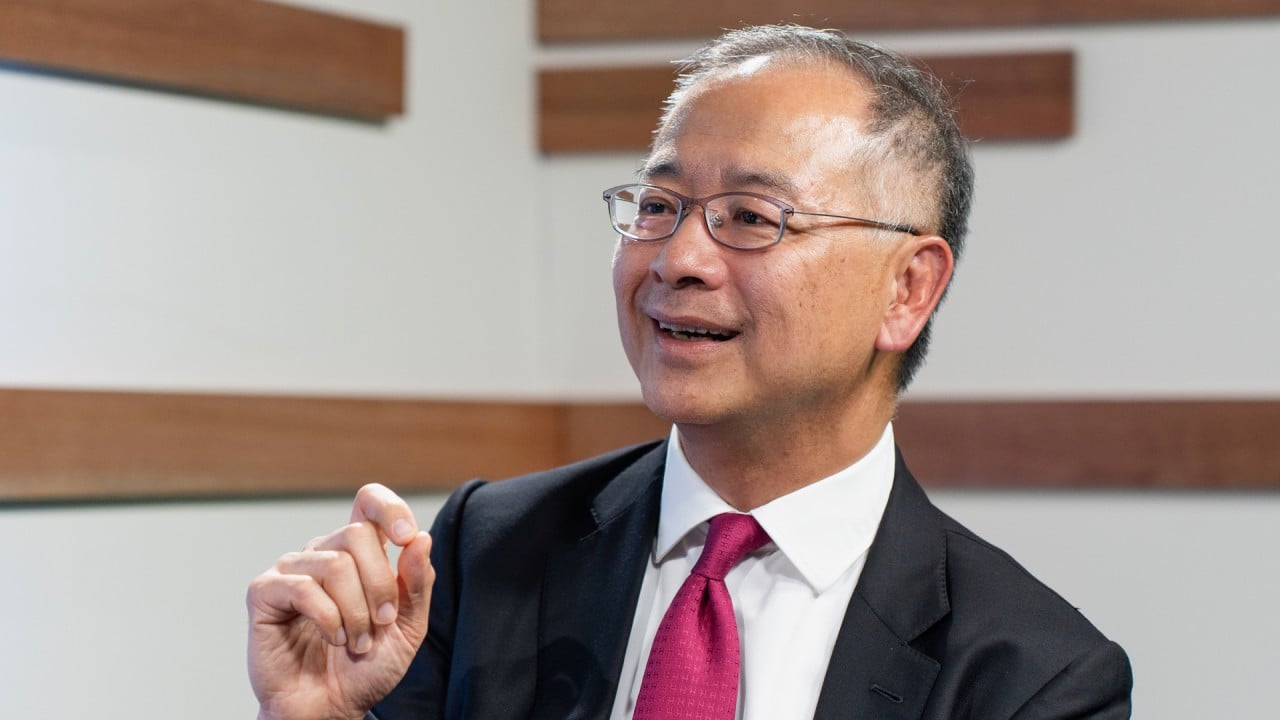

In 1983, “the uncertainties surrounding the transitional arrangements affected the general confidence on the future of Hong Kong,” said Joseph Yam Chi-kwong, who was then the principal assistant secretary for monetary affairs in the Hong Kong government.

Some businesses refused to accept payment in the local currency, insisting on US dollars. Such was the panic that many consumers stocked up on household necessities ranging from foodstuff to toilet paper.

To stabilise the local currency, the government introduced the linked exchange rate system (LERS), pegging its value at HK$7.80 per dollar. The HKMA was only formed in April 1993, with Yam serving as its first chief executive through September 2009. A trading band of between HK$7.7500 and HK$7.8500 was only introduced in 2005, giving the local currency some room to move against the US dollar.

“With China’s interest rates expected to stay lower than US rates, due to lower Chinese inflation, embracing the yuan would stabilise Hong Kong’s asset markets,” said Xie, who previously worked as an economist at Morgan Stanley and the World Bank.

Hong Kong’s monetary policy is conducted in lockstep with the US Federal Reserve to preserve the peg, even if the cycles of the two economies differ. That puts the city at a disadvantage such as when the Fed’s quantitative easing unleashed a torrent of cheap funds that led to a property bull run in Hong Kong.

The current environment poses a similar dilemma, said Chan, the former Citibank trader. The dollar peg has created problems from time to time because the system forces the HKMA to align the city’s interest rates with US dollar interest rate movements, he said.

“Hong Kong’s current economy is weak, inflation is normal and the property market is soft,” said Chan. “We do not need and could not afford to have high interest rates, but we still need to follow the US interest rate tightening because of the peg.”

Agustin Carstens, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), also endorsed the peg, saying it had given the city monetary stability.

“Certainly the dynamism of Hong Kong and the region as a whole has preserved this economy in a very bright and vibrant state, and kept it very competitive,” Carstens said in an interview with the Post last December.

Even small businesses in the city have given their vote of confidence to the peg. Vince Chan, the owner of Peanut Florist in Wan Chai, wants the fixed exchange rate system to stay.

This is the main culprit behind the Hong Kong dollar’s slump

This is the main culprit behind the Hong Kong dollar’s slump

“I import flowers from Holland, South Africa and sometimes from Japan, at prices which are usually expressed in US dollars,” Chan said. “A fixed exchange rate protects me from exchange-rate losses. It allowed me to run my business these past 26 years. A high fluctuation of the currency will hurt my business.”

The biggest hurdle that makes it impractical for Hong Kong dollar to be pegged to the yuan is the Chinese currency’s non-convertibility.

To serve as an anchor currency, Hong Kong needs something that is “fully compatible with a deep global treasury market or bond market that can be accessed anytime” to adjust the exchange rates, Yue said.

Indeed, there is “no economic reason” for China to peg the Hong Kong dollar to the yuan, said Raymond Yeung, chief economist for Greater China at ANZ Banking Group.

“The mainland authorities can simply increase the circulation of the offshore yuan to boost the internationalisation of yuan,” he said in a note to clients. “It does not need to change the peg to achieve such a result.”

The Hong Kong dollar is “a symbol of globalisation” and the peg was still “valuable to the national interest”, showing the city remains a free market. The e-HKD projects, and other virtual asset development, will be another chance to enhance its international status, raising its appeal as a possible reserve currency in the new digital economy era, he added.

But Chan, the former Citibank currency trader, said there was room for discussion regarding the future of Hong Kong dollar peg.

“The historical mission of the peg is largely complete,” he said. “It is time to review the possibility of aligning our exchange rate more with the Chinese yuan rather than the US dollar, because the yuan is on course to becoming an international currency.”