Accountants, corporate management, and investors would likely all agree that better guidance is needed for the accounting, valuation, disclosure, and reporting of crypto assets. FASB has recognized the growing prevalence and importance of crypto assets and released an exposure draft on the subject earlier this year. But while businesses wait for finalized guidance, entities that rely upon crypto must still issue audited financial statements. This article reviews the potential implications of the exposure draft and examines the existing reporting from three entities materially exposed to the crypto market.

***

In March 2023, FASB issued an exposure draft (ED), “Intangibles—Goodwill and Other-Crypto Assets (Subtopic 350-60)” that identified weaknesses in reporting for crypto assets. While the ED is a work in progress, it indicates the direction of possible changes. The digital asset economy presents opportunities and problems for both investors and auditors, as regulators struggle to define a crypto asset. Without a clear definition of crypto as a security or a commodity, reporting has not been uniform or consistent. While the ED works its way through due process, U.S. accountants are still tasked with auditing companies that have material crypto exposure under current GAAP.

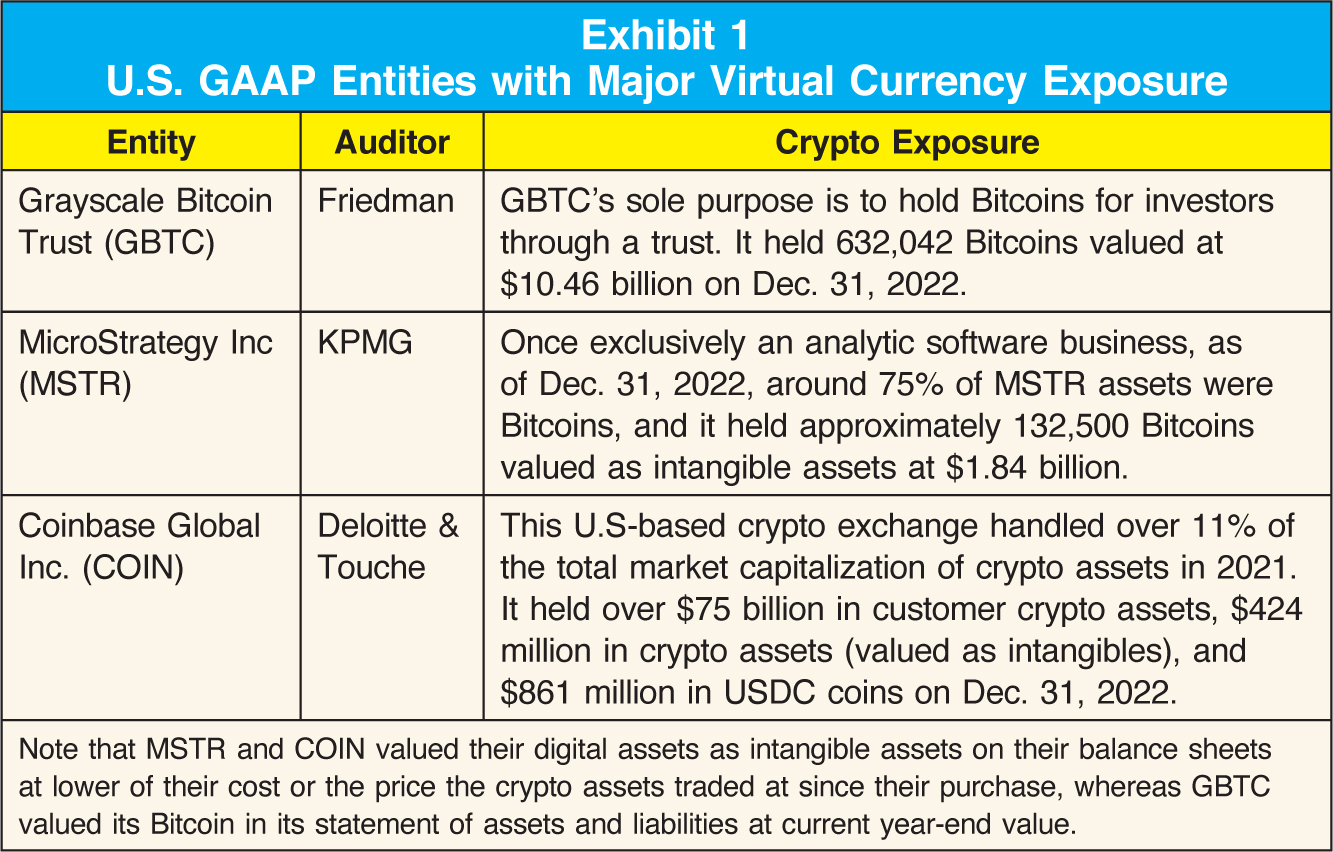

A review of the 2022 audits of financial statements for three publicly traded U.S.-based companies—Grayscale Bitcoin Trust, MicroStrategy Inc., and Coinbase Global Inc.—demonstrates the limitations that CPAs encounter when auditing crypto: specifically, in virtual currency financial reporting and disclosures (Exhibit 1). The financial statements of these crypto-based entities allow for the identification and assessment of crypto risks and relevant issues. The auditors appear to be making good-faith efforts to apply accounting standards. The perilous nature of the crypto environment is detailed in these annual reports. Based on this reporting, the due diligence of investors in the crypto arena may be questioned. This article examines proposed and current GAAP for crypto and identifies areas of concern, first through a summary of the ED and then a review of current reporting using the financials of the three crypto-based entities noted above. It remains to be seen whether the ED in its final form will address all the areas of concern.

Exhibit 1

U.S. GAAP Entities with Major Virtual Currency Exposure

Current Regulatory Concerns

The SEC issued a stark warning for investors in cryptocurrency on March 23, 2023. In the statement, the SEC advised market participants about the inherently risky landscape surrounding crypto assets and the exchanges on which they are traded. Among the issues were the risk and volatility facing investors and the lack of sufficient financial reporting to ensure the provision of useful information. In June 2023, the SEC sued Binance (the largest crypto trading platform) and Coinbase. These actions are two of over dozens of SEC filings against entities concerning crypto assets and related transactions (https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-110).

The SEC sought to freeze Binance’s U.S. assets, but the court encouraged and approved a settlement between them that protects the assets of U.S. customers and allows Binance to engage in ordinary business transactions. According to SEC Chair Gary Ginsler, “Through thirteen charges, we allege that Zhao and Binance entities engaged in an extensive web of deception, conflicts of interest, lack of disclosure, and calculated evasion of the law” (https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-101). Regulatory uncertainty was a concern in the 2022 annual reports of Grayscale Bitcoin Trust, MicroStrategy Inc., and Coinbase Global Inc. For example, whether digital assets are securities or commodities remains unresolved, affecting reporting requirements, and their U.S. and global taxation effects are unclear.

FASB’s 2023 Crypto ED

FASB’s ED was issued in response to stakeholder concerns regarding the lack of sufficient authoritative guidance related to the accounting and disclosure of crypto assets. At the heart of these concerns is the use of the cost-less-impairment model; while clearly a conservative approach, this fails to provide decision useful information to investors, lenders, creditors, and other allocators of capital.

In its call for comments, FASB admits the cost-less-impairment model is inadequate and summarizes the problems with current practice:

Specifically, reflecting only on the decreases, but not on the increases, in the value of crypto assets in the financial statements until they are sold does not provide relevant information that reflects (1) the underlying economics of those assets and (2) an entities’ financial position. Certain investors also requested additional disclosures about the types of crypto assets held by entities and changes in those holdings. (p. 1, https://bit.ly/3DLcVPE)

FASB’s proposal to enhance the quality of financial information would apply to crypto assets that meet these six specific criteria:

- Meet the definition of ‘intangible asset’ as defined in the Codification Master Glossary.

- Do not provide the asset hold with enforceable rights to, or claims on, underlying goods, services, or other assets.

- Are created or reside on a distributed ledger based on blockchain technology.

- Are secured through cryptography.

- Are fungible.

- Are not created or issued by the reporting entity or its related parties. (p. 1, https://bit.ly/3DLcVPE)

Unless exempted by industry-specific GAAP, crypto assets are considered indefinite-lived intangible assets that are subject to periodic impairment testing. Under current GAAP, should the carrying amount exceed the fair market value (FMV), then the crypto asset is written down (i.e., permanent impairment recognized) and the decline in value is recognized in the income statement as a loss. Any recovery of the decline in value is not recognized in future periods, thus making the impairment permanent.

The ED calls for crypto asset FMV changes to be recognized each reporting period. When FMV exceeds the carrying amount, the asset would be written up and a gain recognized in the income statement. Conversely, when the carrying amount exceeds FMV, the asset would be written down and a loss recognized. There is no proposed guidance on the treatment of unrealized crypto gains and losses from prior periods (a concern expressed in several comment letters). Cumulative unrealized losses were material amounts for MicroStrategy and Coinbase, as discussed below.

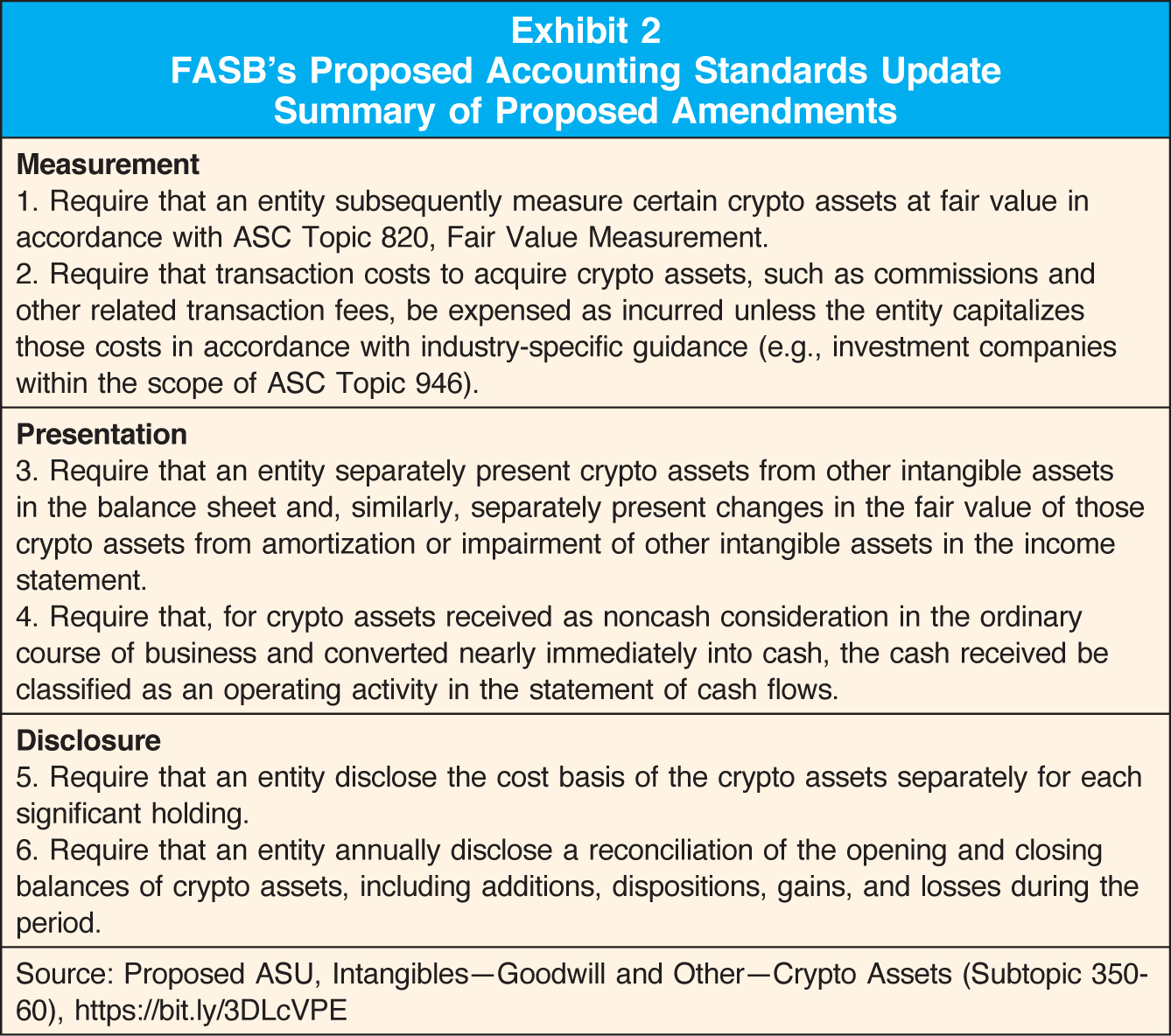

The ED focuses on three dimensions of financial reporting for crypto assets including measurement, presentation, and disclosure. Exhibit 2 provides a summary of the six recommended changes to GAAP proposed by the FASB.

Exhibit 2

FASB’s Proposed Accounting Standards Update Summary of Proposed Amendments

It is worth noting that under the proposed requirements, stakeholders would be provided relatively detailed disclosures in both interim and annual reports. Specifically, financial reports would disclose for each crypto asset held:

- the name of the crypto asset;

- its cost basis;

- fair value at the reporting date; and

- the number of units held. (p. 6, https://bit.ly/3DLcVPE)

The reporting of the above was not consistent or always determinable for Grayscale Bitcoin Trust, MicroStrategy, and Coinbase. Reporting entities would also be required to disclose the specific method employed in the determination of cost basis [e.g., FIFO (first in first out), specific identification].

Crypto Comment Letters

From the more than 80 comment letters received by FASB, there appears to be general support among public accounting firms to the general framework of the ED (https://bit.ly/440l8Kn). Among the strengths identified was the specificity of the disclosures relating to each of the crypto assets held. The additional disclosure requirements, if adopted, could serve to enhance both the decision usefulness of financial reports and the auditability of the crypto asset class. In addition, the proposed requirements would likely serve the intended purpose of “normalizing” the accounting and disclosure of crypto assets consistent with the treatment of other intangible assets.

In its comment letter, the AICPA’s Financial Reporting Executive Committee (FinREC) indicated broad support for FASB’s proposal. But it expressed concerns as to the treatment of cumulative unrealized gains and losses related to crypto assets held by reporting entities. The AICPA’s concern was consistent with other comment letters:

[T]he Proposed ASU does not provide explicit guidance on whether an entity presents gains and losses in the operating or non-operating income subtotal in its income statement if it otherwise presents a subtotal for operating income in its income statement. In addition, based on the proposed amendments, it is not clear whether an entity could elect to separately present unrealized gains and losses from realized gains and losses on the income statement. Furthermore, given the lack of explicit guidance, FinREC believes that entities that choose to separately present unrealized gains and losses from realized gains and losses may do so inconsistently. (https://bit.ly/3Qwi3P5)

Suggested Disclosures Rejected

The ED observed that other suggested crypto disclosures were rejected, “including additional information about gains and losses, the nature and purpose of holding crypto assets, information about pricing, and information about the cryptographic.” FASB stated that some of this “similar information” could be obtained by existing and proposed disclosures. Other recommended disclosures were stated to be “too detailed and not currently required for similar assets” (note 1, p. 34, https://bit.ly/3DLcVPE).

Arguments for and against FASB’s rejection of additional disclosures on how crypto assets are priced did appear in at least two comment letters, and the feedback was mixed. Cryptio, an enterprise-grade crypto accounting and tax Software as a Service (SaaS) solution, argued for the inclusion of pricing in the proposed standard: “Pricing can vary significantly due to the limitations companies face with access to data. … More clarity on how companies are pricing their assets, and ultimately how they are coming up with their fair value will add value” (https://bit.ly/3QwLaSo). In contrast, CliftonLarsonAllen, LLP, a large U.S. national accounting firm, concluded that the exclusion of the issue of pricing in the ED was appropriate: “additional information about gains and losses, the nature and purpose of holding crypto assets, information about pricing, and information about the cryptographic private key should not be required … this information, if required, can generally be obtained by users of private company financial statements by contacting management” (https://bit.ly/3QxxqH7).

With respect to trading volume, there are numerous reports that over 80% of the trading volume is “false or noneconomic.” The SEC’s June 2023 lawsuit against Binance (“the largest crypto asset trading platform in the world”) alleges that Binance “misled … U.S. customers and equity investors concerning the existence and adequacy of market surveillance and controls to detect and prevent manipulative trading” on the trading platform (https://bit.ly/3YvvZe8).

It is uncertain which path FASB will take in finalizing the draft, but clearly more disclosures will be required; the extent and detail yet to be determined. In the interim, auditors will have to continue exercising their best efforts, as they did in the illustrative cases below.

GAAP Based Entities with Material Crypto Exposure

An examination of Grayscale Bitcoin Trust, MicroStrategy, and Coinbase’s 2022 financial statements, financial footnotes, audit opinions, and management write-ups reveals relevant accounting procedures in the crypto arena. The lack of authoritative accounting guidance and unclear directions for crypto assets reporting was expressed in the Coinbase 2022 10K:

As such, there remains significant uncertainty on how companies can account for crypto assets transactions, cryptoassets, and related revenue. Uncertainties in or changes to regulatory or financial accounting standards could result in the need to change our accounting methods and restate our financial statements and impair our ability to provide timely and accurate financial information, which could adversely affect our financial statements, result in a loss of investor confidence, and more generally impact our business, operating results, and financial condition.

(Coinbase 2022 10K, p. 69)

MicroStrategy and Coinbase valued their crypto holdings as intangible assets, in accordance with ASC Topic 350, “Intangibles—Goodwill and Other.” Impairment losses are recognized, but their value is not increased for any increase in price until the digital asset is sold. Losses are based on the lower of their cost or the price the crypto assets have traded at since their purchase. In contrast, Grayscale Bitcoin Trust uses ASC Topic 946, “Financial Services—Investment Companies,” in reporting its results (2022 10k, p. 76). Here “accumulated net change in unrealized appreciation” is shown in its financial statements (2022 10k, p. F-7). Grayscale’s reporting of its crypto fair value seems similar to what the ED is currently proposing.

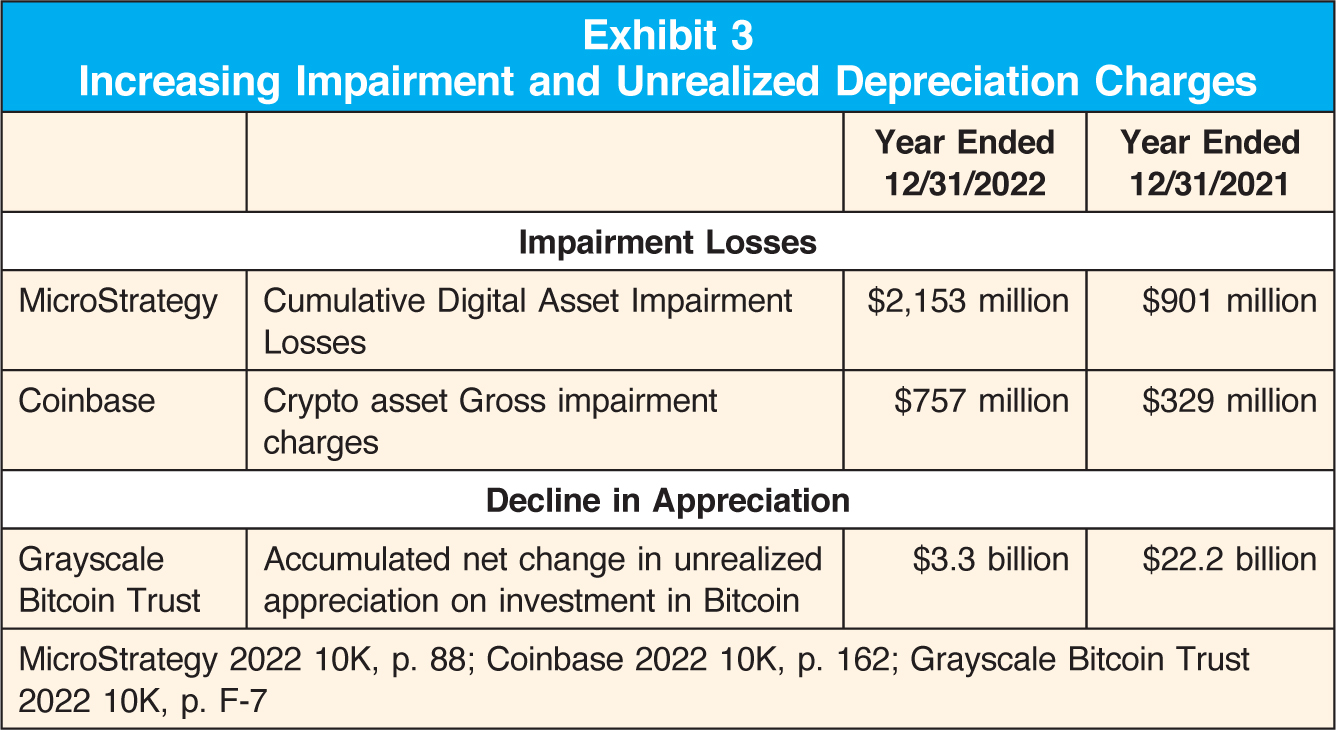

As shown in Exhibit 3, cumulative or gross impairment losses for MicroStrategy and Coinbase were material in 2022. At the end of 2022, MicroStrategy had more than $2 billion in “cumulative digital asset impairment losses” and Coinbase had over $750 million in “crypto asset gross impairment charges.” Grayscale Bitcoin Trust, which had a $22.2 billion accumulated unrealized appreciation at the end of 2021, was down to $3.3 billion on September 30, 2022, a decline of 85% or nearly $19 billion.

Exhibit 3

Increasing Impairment and Unrealized Depreciation Charges

Another complicating factor is that impairment losses and their unknown tax consequences in the crypto arena make deferred tax assets difficult to estimate. According to MicroStrategy, this area is “inherently uncertain” (net operating loss [NOL] carryforwards, applicable tax rates, and tax planning all come into play). MicroStrategy reported a $511 million valuation allowance for “deferred tax asset related to the impairment on its Bitcoin holdings” (2022 10K, p. 18).

Concerns over Crypto Pricing

As observed in the ED, additional disclosure on “information on pricing” was rejected. In 2022, the management sections of MicroStrategy and Grayscale’s financial statements identified a critical and material risk factor of crypto trading; over 80% of Bitcoin pricing volume is potentially unreliable. A similar concern was expressed in MicroStrategy’s 2021 10K. Grayscale Bitcoin Trust’s 2022 10K stated:

For example, in 2019 there were reports claiming that 80–95% of Bitcoin trading volume on Digital Asset Exchanges was false or non-economic in nature, with specific focus on unregulated exchanges located outside of the United States. Such reports may indicate that the Digital Asset Exchange Market is significantly smaller than expected and that the U.S. makes up a significantly larger percentage of the Digital Asset Exchange Market than is commonly understood. Nonetheless, any actual or perceived false trading in the Digital Asset Exchange Market, and any other fraudulent or manipulative acts and practices, could adversely affect the value of Bitcoin and/or negatively affect the market perception of Bitcoin. (p. 54)

If 80% or more of the trading volume in crypto is fraudulent, then the credibility of Bitcoin’s stated or reported values is inherently suspect. The SEC’s 2023 lawsuit alleges that Binance Holdings allowed wash sales on its platform. The Wall Street Journal called this “one of the most basic forms of manipulative trading” (https://on.wsj.com/3QyimZV). Here a trader has both buy and sell orders to be transacted with themselves to inflate pricing.

Note 7 in Grayscale Bitcoin Trust’s 2022 financial statements observes that digital assets trade within an environment with no regulated central pricing. This is another risk and hinders the ability to price many crypto holdings uniformly (unlike U.S. stocks, which have a definitive closing price). Regarding Bitcoin, the most established crypto asset, Grayscale’s 2022 10K stated:

There is currently no clearing house for Bitcoin, nor is there a central or major depository for the custody of Bitcoin. …. Further, transactions in Bitcoin are irrevocable. Stolen or incorrectly transferred Bitcoin may be irretrievable. As a result, any incorrectly executed Bitcoin transactions could adversely affect an investment in the Shares. (p. F-13)

Even valuing digital assets under the GAAP fair value hierarchy differs, with some entities valuing them under level 1 (active market) and some under level 2 (not active).

Other Risks Highlighted

The financial statements and management write-ups highlighted other risks. Grayscale Bitcoin Trust observed that risks include private keys being “lost, destroyed or otherwise compromised” (which could be irreversible), use of peer-to-peer networks, use of third-party services, and the commingling of assets—all of which should be warning signs for investors. Regarding commingling, it stated:

The Bitcoin held by the Trust are commingled and the Trust’s shareholders have no specific rights to any specific Bitcoin. In the event of the insolvency of the Trust, its assets may be inadequate to satisfy a claim by its shareholders.

(2022 10K, page F-13)

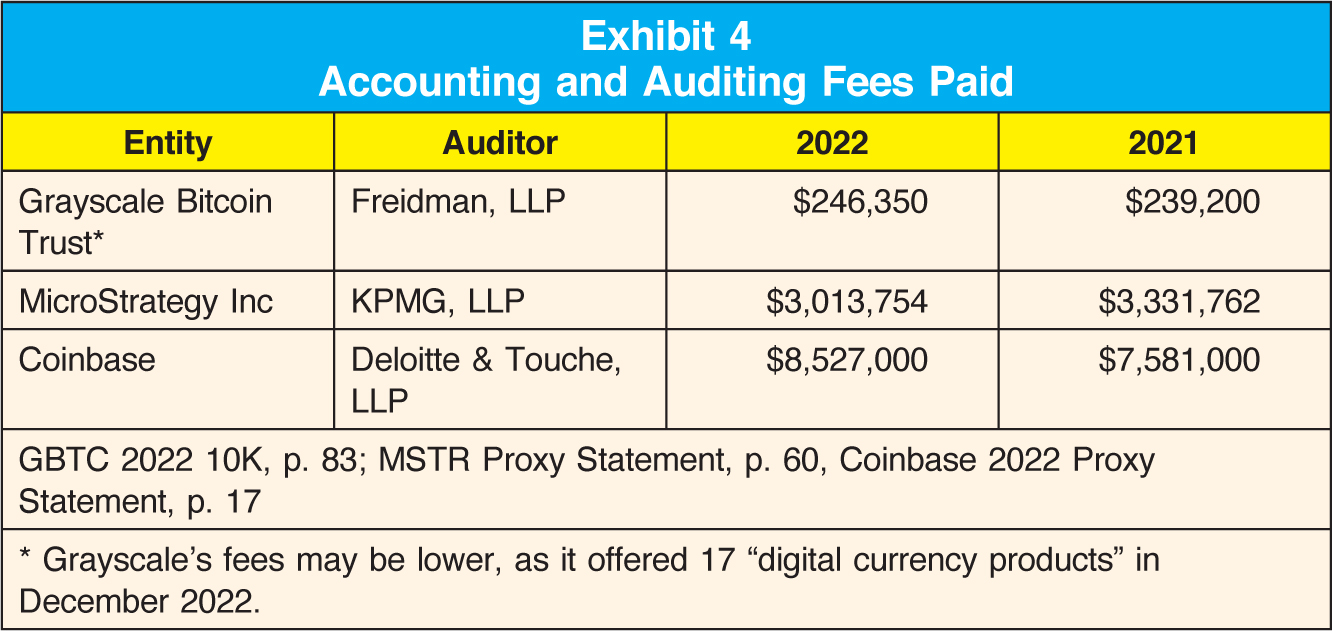

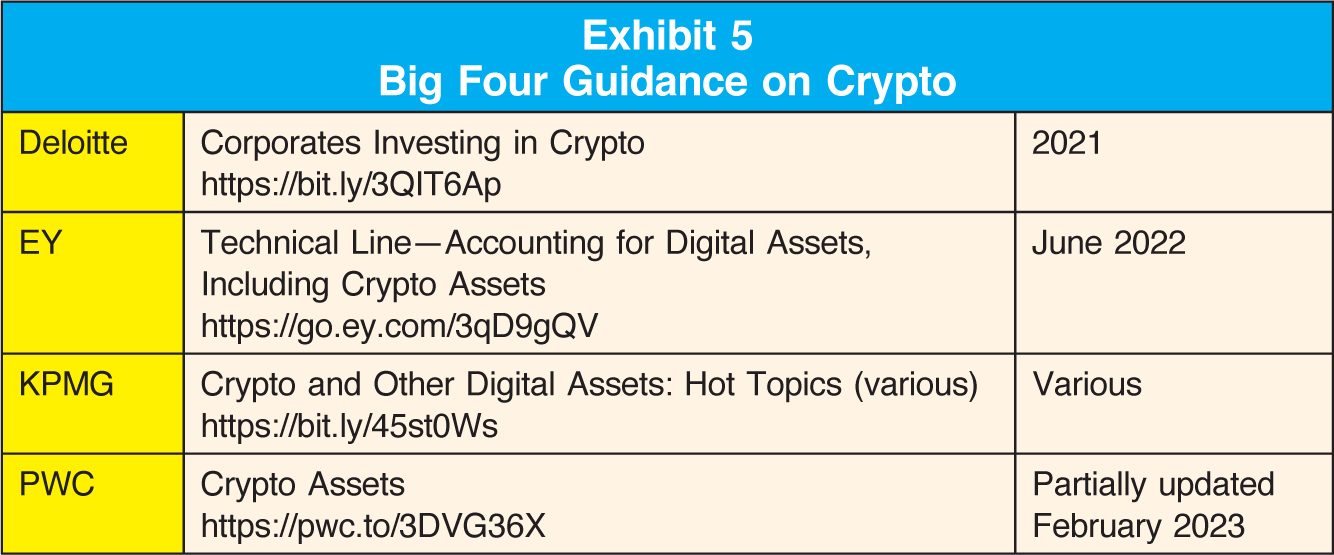

Both KPMG (auditor for MicroStrategy) and Deloitte & Touche (auditor for Coinbase) gave unqualified audit opinions but highlighted elements of crypto accounting as critical audit matters. Given the risks identified, some wonder why CPA firms would subject themselves to reputational and lawsuit risks in this area. Exhibit 4 shows the annual accounting fees paid to these firms. Firms may be willing to take reputational risks not only for these fees, but also to have a first-mover advantage in a new asset class that some believe could fundamentally change wealth storage. Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG, and PricewaterhouseCoopers have information publications for accounting and investing in digital assets (Exhibit 5). In addition, the IASB and FASB have an ongoing dialogue on digital assets (https://www.ifrs.org/search-results/?query=digital+assets).

Exhibit 4

Accounting and Auditing Fees Paid

Exhibit 5

Big Four Guidance on Crypto

Material Valuation Changes

Total crypto market capitalization declined from a stated high of around $3 trillion in November 2021 to around $850 billion as of year-end 2022 (a decline of over 70%). In June 2023, it had recovered to $1.2 trillion (https://bit.ly/3Ky4vz5). For comparison, the global equity markets are valued at around $100 trillion (https://reut.rs/3qi7uVt). On its initial public offering in April 2021, Coinbase was valued at $85 billion (https://on.wsj.com/3qn02Is). Its value had fallen to $9 billion by the end of December 2022, a nearly 90% decline (https://bit.ly/3DNdLv9). Coinbase’s 2022 10K observed that a major decline in the market price for crypto assets could be problematic:

The increases in value of certain crypto assets, including Bitcoin, from 2016 to 2017, and then again in 2021, were followed by a steep decline in 2018 and again in 2022, which has adversely affected our net revenue and operating results. If the value of crypto assets and transaction volume do not recover or further decline, our ability to generate revenue may suffer and customer demand for our products and services may decline, which could adversely affect our business, operating results and financial condition.

(Coinbase 2022, p. 24)

A Step in the Right Direction

The ED and comment letters show that the current lack of official guidance on crypto limits useful information for decision-makers. An examination of the 2022 annual reports for Grayscale Bitcoin Trust, MicroStrategy, and Coinbase illustrates how problematic the accounting for crypto is. Some question whether FASB’s ED will do enough in requiring more disclosures (e.g., how digital assets are priced).

Grayscale Bitcoin Trust and MicroStrategy’s 2022 annual reports warned that Bitcoin trading volumes could be 80–95% fraudulent. The June 2023 SEC lawsuit against Binance alleged manipulative trading that inflated prices. What would the impact be on Bitcoin’s stated value if wholesale selling occurs? Current trading and pricing of digital assets is at best murky. General risks were disclosed (i.e., government actions and restrictions, loss or theft of private keys, cyberattacks, verification of the existence of digital assets, use of third-party exchanges).

Clearly, crypto assets are problematic to audit under current standards, even though some have made good-faith efforts to apply current standards. Under current GAAP, audited financial statements disclose significant red flags. Whether the ED will successfully address the outstanding issues in the crypto marketplace remains to be seen, but it appears to be moving in the right direction.