Fallen crypto king Sam Bankman-Fried was ‘perfectly positioned to make a religion of himself’

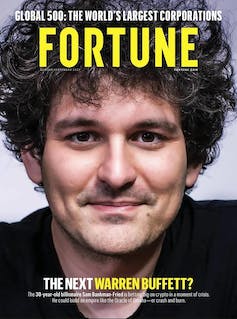

A year ago, Sam Bankman-Fried (often called “SBF”) was on top of the world. He had been on the covers of Forbes, which dubbed him “the richest twentysomething in the world”, and Fortune – the equivalent, for a business leader, of a rock star on Rolling Stone, or an athlete on Sports Illustrated.

He was featured in the prestigious “lunch with the FT” in the Financial Times. He was seen as the responsible face of cryptocurrency. There was even speculation he could become the first trillionaire.

But in late 2022, his FTX crypto trading operation – and the closely related Alameda Research, an investment fund he had founded before FTX – both collapsed.

Bankman-Fried is currently charged with crimes relating to the disappearance of billions of dollars of FTX users’ money. These people did not think they were investing in FTX, or even lending to it. Their funds were just being kept there while they switched between, for example, dollars and bitcoins or between bitcoins and dogecoins. But instead it is claimed that their funds were transferred to Alameda and then lost.

Bankman-Fried is pleading not guilty and has published a statement reading: “I didn’t steal funds, and I certainly didn’t stash billions away.”

Review: Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon – Michael Lewis (Allen Lane)

Bankman-Fried, who was living in the Bahamas at the time of his arrest, now resides in a US prison. He is facing charges that could result in a sentence of more than a century behind bars and has been taunted as “Scam Bankrupt-Fraud”.

His remarkable story has been told by Michael Lewis, the author of Liar’s Poker, a Wall Street story drawing on his own experience as a bond salesman for Salomon Brothers; and the internationally successful book-then-film The Big Short, an account of the financial market shenanigans that led to the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

Lewis, who had extraordinary access to Bankman-Fried while writing, holds the unusual combination of degrees in art history from Princeton and economics from the London School of Economics. As a former bond salesman, he knows his way around financial markets and has seen his share of excess and oversized egos. As a journalist, he is skilled at clear writing about complex finance. He was ideally placed to write this book.

However, he has been widely criticised as too close to his subject. When Bankman-Fried was arrested, Lewis had been shadowing him for nearly a year. And as events unfolded – and even while Bankman-Fried was under house arrest – Lewis was there, taking notes.

Lewis describes himself as having been “totally sold” after his first meeting with Bankman-Fried. And he has called his book “a letter to the jury”. But he rejects criticism of his objectivity as “crazy”.

Read more:

The spectacular collapse of a $30 billion crypto exchange should come as no surprise

Effective altruism and ‘infinite dollars’

Going Infinite derives its title from a question Lewis asked his subject: how much would he need to be paid to sell and walk away from FTX? Bankman-Fried initially replied: $150 billion. He then added he needed “infinite dollars” because he planned to address existential risks facing humanity.

This rather grandiose response was based on a concept called “effective altruism”, inspired by a 1971 essay by Australian philosopher Peter Singer.

Lewis’s example is that instead of becoming a doctor in Africa and helping some people, you can make a fortune and then pay for 40 doctors and help 40 times as many people.

Bankman-Fried claimed his motivation for FTX was to fund effective altruism. Some of his senior executives claimed to share this motivation.

Bankman-Fried felt Donald Trump was an impediment to actions that would make the world a better place. He donated to anti-Trump Republicans and to Democrats. One revelation in the book is that Bankman-Fried contemplated paying Trump not to run again for president. The figure mentioned was US$5 billion, but it is not clear whether this number came from Trump himself.

Read more:

What do we owe future generations? And what can we do to make their world a better place?

The odd life of Sam Bankman-Fried

Bankman-Fried’s parents are both Stanford professors. But there is no obvious factor in his childhood that explains his eccentricities, or why he seemed to have few friends.

Lewis writes that Bankman-Fried had to teach himself facial expressions, and that Bankman-Fried thought he had “an aching hole in my brain where happiness should be”. He skates over Bankman-Fried’s years as a high school nerd, where the place he most felt a kind of belonging was math camp, and as a MIT physics student. And he concludes that the future crypto king was perfectly positioned, emotionally and intellectually, to make a religion of himself.

One of the most interesting parts of the book is the account of Bankman-Fried’s early career at Jane Street Capital, a Wall Street high-frequency trading firm, where interns were encouraged to gamble with each other and with the full-time employees as a way of developing their professional skills. There, Bankman-Fried’s intuition about probability shone.

The “SBF” who emerges from the book has some similarities with the portrait of Elon Musk in the eponymous just-published biography by Walter Isaacson. Both men are convinced they are the smartest guy in any room they are in. And both have the hubris to think the future of humanity depends on them.

Bankman-Fried reportedly said there was a 5% chance he could become US president. The US constitution meant this was one takeover to which the South Africa-born Musk could not aspire.

Isaacson relates a half-hour telephone discussion between Bankman-Fried and Musk about the latter’s takeover bid for Twitter. After consulting colleagues for 15 minutes, with Lewis present, Bankman-Fried was considering contributing “maybe a billion” as part of a consortium being assembled by Musk. But the discussion did not go well. Both apparently thought the other was crazy.

FTX was ‘essentially a casino’

So-called “cryptocurrencies”, like Bitcoin, are rarely used for their original stated purpose of making payments. They are really just speculative tokens with no fundamental value.

Read more:

What is Bitcoin’s fundamental value? That’s a good question

FTX promoted itself as the equivalent of a stock exchange for these cryptocurrencies.

Lewis writes:

The new crypto exchanges had no regulators. They acted as both exchange and custodian: they didn’t just enable you to buy bitcoin but also housed the bitcoin you’d bought.

FTX was no usual business operation. It was barely a business at all. FTX had no chief financial officer, nor even a list of its staff. It had a sort of board of directors, just for appearances. Bankman-Fried was one director, but in a conversation with Lewis, he could not recall the other two. As Lewis puts it, he “just thought grown-ups were pointless”.

Most of the senior staff at FTX and Alameda were friends of Bankman-Fried (although many have since turned on him, whether from a belated sense of shame or to try to wrangle shorter prison sentences). They lived and worked in a luxury compound in the Bahamas, a sunny place for shady people (as Somerset Maugham once described Monaco).

Apart from the luxury accommodation, there were other extravagances, such as food and chartered planes. Clothes were not one of them. Until his recent court appearances, Bankman-Fried was rarely seen in anything but a t-shirt and shorts – no matter the occasion.

One of his senior employees, Zane Tackett, told Lewis:

His oddness mixed with just how smart he was allowed you to wave away a lot of the concerns. The question of why just goes away.

FTX was essentially a casino. But Bankman-Fried both owned the casino and was gambling in it – apparently with other people’s chips. Alameda Research seemed to be making large bets with money transferred from the accounts of FTX customers.

While Alameda operated in the shadows, huge amounts were spent promoting FTX.

FTX spent tens of millions making an expensive advertisment featuring Larry David comparing crypto to the wheel, democracy and the moon landing. (It has already been screened at the trial.) At least, unlike Katy Perry, Larry can claim that in the advert he was sceptical!

After FTX collapsed, John Ray, the bankruptcy expert tasked with sorting out the mess, remarked: “Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information.” And he had handled Enron!

Accused of having stolen billions

Somewhere between US$5 billion and US$10 billion of customers’ money from FTX seems to have disappeared. Lewis writes that it may have been lost in losing bets by Alameda. Lewis estimates that Bankman-Fried made over 300 separate investments – one every three days. There were certainly some poor investments, such as 101 Bored Ape NFTs, bought for US$24 million. These have lost about 90% of their value.

Read more:

Are NFTs really dead and buried? All signs point to ‘yes’

Bankman-Fried has been accused of having stolen “billions from thousands of people”. His lawyers responded that he is being painted as a “cartoon villian”. A lot will depend on whether the jury regards him as a calculating liar or an idiot savant “math nerd”, hopelessly out of his depth as a manager.

Another interesting aspect yet to emerge is how the top Wall Street and Silicon Valley investors explain their naivety in trusting Bankman-Fried. How do you explain what the Financial Times called the “legend of Sam”?

Michael Lewis has written ‘a letter to the jury’

Lewis seems inclined towards the view Bankman-Fried may not have been deliberately fraudulent. He has spoken of a “mob mentality” and a “very quick rush to judgement”.

Biographers seem to sometimes experience a literary equivalent of the now much-debated “Stockholm syndrome”. If they are embedded with their subject, they may come to share their world view.

Another recent book that profiles Bankman-Fried, Number Go Up by Zeke Faux, paints a similar picture in many ways – but is more sceptical about his motivations.

Faux makes the telling point that many of the punters lured in by the advertisements for FTX lost money they could not afford to lose. This is hardly the act of an altruist. Faux described Lewis as asking his subject questions “so fawning, they seemed inappropriate for a journalist” at an FTX-sponsored conference.

Like Lewis’s other books on financial shenanigans, Going Infinite does a good job of explaining complex financial concepts. And it is an entertaining read about an unusual and intriguing personality. But it does seem like it was rushed out to coincide with the trial. There is no index, for example. It will need a second edition once the current court case is resolved.