The launch of PSD2 in the UK made Open Banking a regulatory requirement. As we arrive at the six year anniversary, we’re looking at what’s changed… and what hasn’t.

Primarily impacting payments up until this point, the Open Banking mandate was intended to boost competition amongst service providers and open a raft of opportunities for both consumers and businesses.

Through bank APIs, customers would be able to consent to the sharing of information with third parties. In theory it’s the future of money and it certainly has taken hold in places, just not to the extent that many had hoped for. It’s possible that removing sole custody of user data and opening the door to increased competition might have been a tough sell for many established banks.

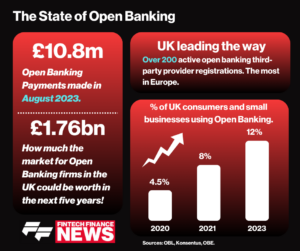

Still, there are signs of increased usage and impact. According to the latest research from implementation entity, Open Banking Ltd., at least 11% of British consumers are active users of open banking, which is an increase from 7% in December 2021. In June 2023, 9.7 million open banking payments were made which is close to a 90% increase on the previous year. That jumped to 10.8 million the following month.

There’s no denying that there is an increased appetite for open banking as consumer behaviour changes, but progress has been slow. Let’s look at where we are now, with commentary from experts in the field including Jas Shah, Hans Tesselaar, Tom Burton and more.

UK leading the way

There has definitely been progress in this area. According to Helen Child of Open Banking Excellence, Open Banking has created around 4,800 jobs and is expected to generate more than $416bn in new revenues globally.

Their research also said the potential market for UK firms will be worth £1.76bn over the next five years. Indeed, Britain has the opportunity to push forward global regulations and pioneer the cause. One major use case taking place at an institutional level is HMRC launching APIs to help third parties log in to key tax services on behalf of their clients. More than £14 billion worth of tax payments have already been made using open banking technology.

The most exciting use cases we’ve seen are from pioneering fintechs, some of whom were recognised at our FF Awards in November.

Of course, we had to have a category specifically focused on Open Banking, which was won by JS Group and their partnership with NatWest Open Banking API, Payit. This award-winning solution has been used in JS Group’s Aspire Cash platform, which streamlines the awarding of funds for university students and gives the institution insights into how the cash is used. This was a case study with an important impact on those struggling with cost-of-living pressures and shows how Open Banking can help people in the day to day.

Another example that stood out was lending disruptor Plend’s award winning partnership with GoCardless. Plend customers use GoCardless’s Instant Bank Pay feature to make Variable Recurring Payments, an exciting use case of Open Banking that is only just starting to materialise. With this, users are able to make changes to ongoing payments to suit their circumstances which reduces manual work on the vendor side too.

It was also recently announced that GoCardless had extended its relationship with JustGiving to become the online donation platform’s exclusive open banking payment provider. Both instances are areas where Variable Recurring Payments could play a big role. Tom Burton, from GoCardless told us “Our customers have already seen benefits for them and their payers through sweeping VRPs… If we can make some headway on commercial VRPs this year, we are one step closer to making open banking payments a true challenger to cards.”

“There are some bureaucratic changes that need to happen such as establishing the structure, governance and funding of the Open Banking governing body itself to help speed up delivery of items on the Open Banking roadmap, which was supposed to happen in 2023. That’s the first step”

Other interesting use cases that were recognised in the Open Banking Limited report include “using open banking data to build a pre-qualified rental profile for prospective tenants to share with landlords, and an SME finance platform that offers funding through a revenue share model.” Data driven services could also help companies with increased productivity and real-time cash flow insights.

Fintech and Open Banking consultant Jas Shah told me that any concern around Open Banking not meeting its potential, needs to be looked at relative to “the supersonic growth of other initiates like UPI in India and Pix in Brazil.”

In actual fact, progress has been made here and he highlights a “shift away from the ‘easy’ products that use AIS to categorise transactions, to more feature reach, customer-centric products like BuildMyCreditScore from the Currensea team that helps customers build credit, or using Open Banking to help SMEs understand their finance options, as well as pay-by-bank at a number of online retailers. This all contributes to better consumer understanding and widespread adoption.”

A slow burn

We can’t ignore however, that general consensus that Open Banking has so far failed to live up to its potential. And the numbers, although rising, are still small.

Six years in, following a slow adoption by the major banks, it is still a relatively small proportion of British consumers that actively use open banking enabled A2A payments. Card payments still reign supreme and Tony Craddock, director-general of the Payments Association said, “there’s no strong incentive for consumers to use account-to-account payments instead of card payments.” With very few people outside the industry even knowing what Open Banking means, there’s unlikely to be any pressure from the consumer to do anything differently to what they already do.

Hans Tesselaar, executive director at BIAN, commenting on the current state of Open Banking offered a similar concern, saying “While there have been some developments since its inception five years ago, the fact that open banking is primarily initiated and supported by regulators and not consumer demand means that these have been minor.”

He also pointed out the hesitance from players in the industry “to give away the advantage of their valuable data, and receive limited benefits in return.”

Even assuming consumers become aware of products that make their life easier, an understandable concern would be around data protection and security.

Of course, PSD2 was introduced with the intention of protecting consumer data, but ‘Open banking’ doesn’t exactly clarify that this is happening. The potential for an established commercial model for using a bank’s APIs hasn’t yet been solidified, but in theory, once there is a mandate to make multiple layers of customer data available, it could go to the highest bidder. Even if there are multiple security protocols in place, it’s easy to understand why some users may be hesitant about getting on board.

On this, James Hickman, CCO of Open Banking provider Ecospend, said “while these payments do not need the same level of consumer protection as card payments, there does need to be more clarity in some areas, including liability for payments made via Open Banking.”

He does stress that “the technology itself has been designed to be safe in a world which has undergone digital transformation, and to combat the payment security threats that come with that.”

Certain amounts of inbuilt security such as biometric authentication, should make Open Banking payments safer than card but he says that “companies also have a role to play in making Open Banking as safe as possible to ensure the future success of these solutions. For example, variable recurring payments (VRPs) can only flourish if the relevant consumer protection framework is watertight.”

The other major issue that could be slowing progress is linked to the cost of implementing APIs in the first place. For them to work effectively, the messaging architecture for payments needs to be solid. For this to be the case, Craddock believes that third party payment providers may need to start paying for access.

In October I spoke to Martin Herlinghaus from Aevi, who said the potential for data transfer to have a fee attached is “a good thing, as data is a highly valuable asset and requires the necessary safeguards to be protected, which costs money.” But he did caution against the danger that “certain providers could use the charging model as an unjustified toll for third parties to secure their own position.”

We recently witnessed the failure of a major experiment in open banking with the beginning of a split between Goldman Sachs and Apple, after the relationship proved costly for the bank. One of the big questions following that is whether such a relationship with non-financial brands like Apple is even viable for banks.

Will this be the year?

So, the question everyone wants to know is, will this be the year we really start to see Open Banking take off?

Tesselaar doesn’t think so. “Although I expect some progress to be made, the steps will be too small to create a real wave of change. This is because there is still a siloed approach globally. Since Brexit, the UK has had limited access across this market, and can’t afford to reduce its position on the global stage. To avoid this, the UK government would do well to collaborate with industry players, to ensure that it doesn’t cut itself off.”

Shah is a little more pragmatic and suggests some of the things that need to change going forward. “There are some bureaucratic changes that need to happen such as establishing the structure, governance and funding of the Open Banking governing body itself to help speed up delivery of items on the Open Banking roadmap, which was supposed to happen in 2023. That’s the first step.

“Our customers have already seen benefits for them and their payers through sweeping VRPs… If we can make some headway on commercial VRPs this year, we are one step closer to making open banking payments a true challenger to cards.”

“From a consumer point of view, having more feature rich PFM tools like Plum and Cleo will increase consumer adoption from the AIS side but I think a lot of the growth in 2024 will happen on the B2B side with many SME finance and management tools using Open Banking to power finance eligibility, finance management, tax payments, and B2B payments.”

The Joint Regulatory Oversight Committee recently published an update on their plans for this year including the development of premium APIs and piloting commercial models as well as a blueprint for rolling out non-sweeping VRPs. The intention it seems is that legislation will arise off the back of this in 2024, to support a long term framework for Open Banking. As with any such report it can sometimes feel like a lot of talk and not a lot of genuine results. Time will tell.

On the potential use cases still to be explored this year, Shah suggested two we should look out for. “Firstly, In-person Pay by Bank – Yes, cards will continue to dominate in-person transactions where the goal is fast and convenient. But there are many other areas where spending is more experiential. Like at a restaurant where a payment can be parcelled up with a tip, a review and maybe a sign-up to the restaurant’s newsletter. Or in retail where the in-person payment experience can include bespoke offers and loyalty programs, all with a branded end-to-end payment experience and using a Pay by Bank flow. I know of at least one company that will shake things up with in-person OB payments this year (!)…”

“Secondly, P2P payments – Different geographies give rise to different fintech innovations but surprisingly the UK hasn’t seen anything like Venmo in the US, despite the need. Yes, the UK’s bank to bank payment flow is popular with consumers but it’s not convenient for things like splitting restaurant bills, contributing to shared gifts, sorting out holiday payments etc, hence the rise of apps like Splitwise. 2024 will see more Open Banking + Faster Payments based products trying to build a P2P niche.”

One thing is for sure, there’s plenty of interest in the subject and a lot of people invested in moving it forward. Burton had an interesting alternative perspective on what the focus should be this year.

“Instead of searching out new use cases for open banking, we think there’s still a way to go to optimise for existing use cases. At a fundamental level, open banking payments would benefit from greater conversion rates, more consumer awareness, and a more consistent user experience across banks. It’s not just us asking for these basic building blocks; JROC reports that were published in 2023 on the future of open banking, plus the Future of Payments Review, highlight these ‘must-haves’ too. In addition, we should be very focused on delivering commercial VRPs (cVRPs)… for early adopter segments like financial services initially. Nailing that down and proving cVRPs’ value to customers will be an important stepping stone for expanding to other sectors.”