A symbiotic relationship

Following the recent U.S. banking turmoil, U.S. commercial real estate

(CRE) has become a hot topic among market participants. CRE relies heavily

on small and midsize banks for financing, which just so happen to be the

most stressed financial institutions. Overall, the commercial property

industry in the U.S. owes $1.9 trillion to these banks, or twice what it

owes to large banks ($0.9 trillion), according to the Mortgage Brokers

Association. Small and midsize banks are heavily exposed to CRE, which

accounts for as much as 43 percent of their outstanding loans.

CRE is a key component of U.S. small and midsize banks’ lending portfolio

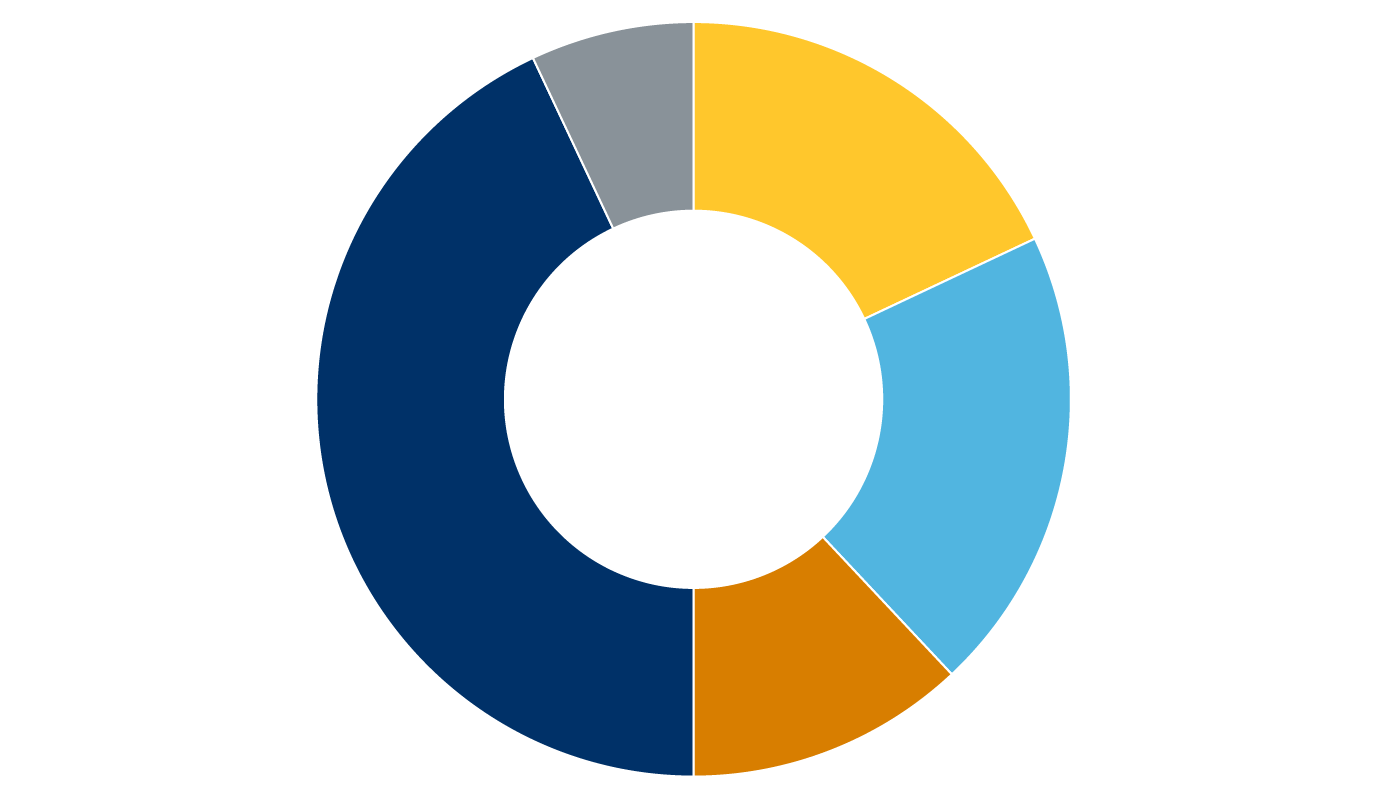

Bubble chart showing the composition of U.S. small and midsize banks’

lending portfolio. CRE represents a hefty 43 percent of the portfolio,

by far the largest component. It is followed by residential mortgages

(20 percent) and commercial and industrial loans (18 percent).

Additional components shown are Other consumer (12 percent) and Other

(7 percent).

-

CRE (43%)

-

Commercial and industrial loans (18%)

-

Residential mortgages (20%)

-

Other consumer (12%)

-

Other (7%)

Source – RBC Wealth Management, FDIC, Refinitiv, Federal Reserve

A sore point

Structural and cyclical issues are darkening CRE’s prospects. Office real

estate is suffering from high vacancy rates due to the post-pandemic

aversion to commuting to a job and the practicalities of the

work-from-home trend. The shift to online shopping accentuated by waves of

lockdowns has also reduced foot traffic at many brick-and-mortar retail

locations. Cyclical issues such as the mass layoffs in tech

industry-dominated areas are compounding these challenges. The U.S. office

vacancy rate reached 12.5 percent in Q4 2022, just below the level seen in

the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008, according to data

provider CoStar.

By nature, CRE involves a high degree of debt and tends to struggle in a

rising interest rate environment. Lower vacancy rates translate into lower

rents. Landlords often have difficulty refinancing as the value of their

buildings slips below that of the loan granted to purchase the properties.

Some may have no other option than to offload their properties at steep

discounts or face bankruptcy.

This would be an additional, unwelcome challenge for those small banks

currently under stress, which are already losing deposits to their larger

competitors and higher-paying money market funds.

A manageable risk

Still, we see reasons to believe the risk of any additional problems at

small and midsize banks due to CRE defaults could be contained. For one,

small banks’ lending contributes less than three percent of U.S. GDP, and

U.S. commercial real estate mortgages constitute less than 20 percent of

all mortgages – it’s the residential market that’s the key. Furthermore, CRE

lending standards have tightened over the past decade. Commercial property

lenders now only offer loans on a maximum of 75 percent of property value,

providing a cushion should values decline. In addition, non-residential

real estate accounts for less than three percent of GDP.

Any CRE default would likely be isolated to a few U.S. regional banks and

smaller lenders, in our view, negatively impacting individual communities.

We think the direct damage to the U.S. economy would be limited, though

defaults would likely lead lenders to tighten lending standards further.

In an environment in which investors are already anxious, we believe any

further meaningful stress on some small and midsize banks could drag down

equities and bond yields, with potential spillover effects for global

financial markets.

How soft are European and Japanese banks’ soft spots?

Banks in Europe and Japan are also under scrutiny from market participants

as they both have proven fragile in the past. Both countries’ banking

channels are outsized, with profitability challenged by the negative

interest rate environment in which they’ve operated for years.

In Europe, similar to the U.S., the concerns centre around a potential

increase in the stock of bad loans and deposit flight which would likely

weaken banks substantially.

Yet European banks do not share the same issues as U.S. regional banks.

Regulation in Europe has made all banks there buy hedges to protect them

against the risk of higher interest rates decreasing the value of their

loans. Liquidity coverage ratios are also much higher in Europe. The

sector is less exposed than its American counterpart to CRE loans and has

strong capital buffers to absorb potential losses. Core equity has surged

close to 15 percent of risk-weighted assets, up from five percent in 2011.

European banks also are less prone to losing deposits to money market

funds as there are fewer cheap and easy-to-access alternatives to bank

accounts than in the U.S. Deposits are mainly retail and insured.

Corporate deposits are mostly broadly diversified, unlike Silicon Valley

Bank’s outsized exposure to tech startups, or that of Credit Suisse’s

family offices (private banking), which withdrew deposits in unison.

Overall, the increase in European regulatory oversight and the balance

sheet clean-up efforts which took place after the 2008 financial crisis

and the European sovereign debt crisis four years later have put the

sector on firmer footing.

But as we see it, tightening lending standards over the past few months

will likely crimp revenue growth somewhat. RBC Capital Markets points out

that the primary market remains effectively shut for banks, a worry at a

time when funding costs are expected by most observers to rise. Following

Credit Suisse’s demise, we think investors in Additional Tier 1 bonds will

likely demand a higher return.

As for Japanese banks, the concern is the effect a sharp increase in the

10-year Japanese government bond yield would have on capital adequacy

ratios, should inflation prove stubborn. Regional banks and Shinkin banks,

cooperative financial institutions serving small and medium-sized

enterprises and local residents, would then have uncomfortably low capital

adequacy ratios. Such a development would bear monitoring, in our view.

Mega institutions, however, would likely cope better, given their healthy

capital adequacy ratios of close to 11 percent, according to S&P

Global.

Quality is key

We see strong reasons to believe that the risks facing U.S. CRE and

European and Japanese banking systems can be contained. But the ongoing

tightening in lending standards in both the U.S. and Europe may be

accentuated should these pressure points flare up. We continue to

recommend investors focus on quality in portfolios, and we prefer

companies with business models that are not sensitive to the business

cycle.

Managing Director, Head of Investment Strategy

RBC Europe Limited