Keynote speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the 22nd Annual International Conference on Policy Challenges for the Financial Sector organised by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Federal Reserve System

Washington, D.C., 1 June 2023

Today I will speak about the lessons we in ECB Banking Supervision are drawing from the recent turmoil in the US and Swiss banking sectors. The recent events were, in my view, the first real test of the regulatory reforms put in place after the global financial crisis. Of course, they came after two major shocks – the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian war in Ukraine – which also tested the banking sector’s resilience. But whereas those shocks originated outside of the banking system and did not lead to widespread questions about banks’ risk management or internal governance, the events in March this year had echoes of 2008. Seemingly unnoticed, significant vulnerabilities had built up in parts of the banking system. When the interest rate environment started changing, those vulnerabilities resulted in a widespread loss of confidence, with rapid deposit outflows leading to some banks failing in the United States, Swiss authorities having to orchestrate the acquisition of Credit Suisse by another Swiss institution, and everyone asking which bank would be next.

But whereas the 2008 crisis ultimately resulted in hundreds of bank failures worldwide, the global banking system has so far weathered the recent storm relatively well.

In my remarks today, I will argue that the resilience we’ve seen in the euro area is evidence that the banking sector is now in the final stage of the difficult and lengthy transition that started in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. European banks today are strong in terms of capital, liquidity and asset quality, and they tend to have well-diversified funding sources and customer bases. Most significantly, the chronic problems of low profitability and weak business models that held the sector back for so long are now finally starting to abate.

The banking union has played an important role here – the change in the institutional regime, with the ECB being assigned supervisory responsibilities, provided an opportunity to shift to strong and intrusive supervision, with unified practices built on the best approaches developed by national authorities in the euro area and at international level. The Single Resolution Framework has also helped strengthen the banking sector, in particular by asking a large set of banks to build up significant loss-absorbing capacity, which makes their liability structure less vulnerable to panic runs.

In my opinion, the lessons we have learnt from the recent turmoil are much more relevant for supervisors than for regulators. Looking at the candid assessment of the US authorities, I strongly share the view that the key takeaways for public authorities relate to the ability of supervisors to escalate issues and ensure prompt remediation by banks. And for these supervisory actions to be targeted, they should be grounded in a strong risk prioritisation framework.

We should abandon the ambition of designing ever-more precise regulations that accurately measure all risks under any circumstances, covering even the most extreme business models and risk configurations. That approach only results in excessive complexity, with burdensome procedures for supervisors and excessive rewards for the few institutions that have the wherewithal to game the system. Instead, we should focus our efforts on empowering supervisory teams, within a strong accountability framework.

And if the recent turmoil teaches us one supervisory lesson above all, it is the importance of ensuring banks have sound internal governance and risk management. Failures in this area are the common theme underpinning recent events in the United States and Switzerland, and they have also been the core theme of many past crises. In my view, this is the one priority area that both banks and supervisors should be focusing on.

The renewed solidity of the euro area banking sector

European banks emerged from the global financial crisis in pretty bad shape. They took longer than their peers in other regions to build up a stronger capital position, deal with their stock of legacy assets and restore their profitability to levels that would attract international investors. While I don’t want to tempt fate, it was comforting to see that, as the recent turbulence spilled over to European markets, European banks managed to withstand the impact. Let me set out what has changed in the euro area banking sector that underpins this new-found resilience.

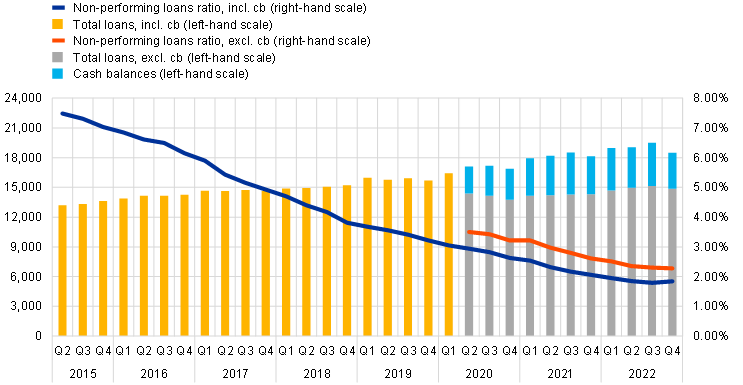

First, asset quality. The European banking sector was mired in high levels of non-performing loans (NPLs) in the period after the global financial crisis. This was an enormously divisive issue within the European Union, going to the heart of divisions between north and south that threatened the integrity of the single currency. Thankfully, this issue is now resolved. The volume of NPLs held by significant banks dropped from around €1 trillion to under €340 billion by the end of December 2022, the lowest level since supervisory data on the banks under ECB supervision were first published in 2015.

Chart 1

Non-performing loans by reference period

(EUR billions; percentages)

Source: ECB. Note: “cb” stands for cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits.

This did not happen by chance. It was the result of focused supervisory pressure by the ECB. Our Guidance on NPLs[1], which we published in 2017, set out supervisory expectations regarding the identification, management, measurement and write-off of NPLs. We supplemented this in 2018 by announcing our supervisory expectations when assessing a bank’s levels of prudential provisions for NPLs[2], which the ECB started to follow in 2021. This announcement played an important role in accelerating the reduction in NPLs. And most recently, we stepped up the pressure on banks in our annual Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) in 2021, where we introduced a targeted capital add-on to Pillar 2 requirements for those banks that reported insufficient coverage of NPLs relative to our expectations while taking the individual circumstances of each bank into account.

A recent report by the European Court of Auditors acknowledged that the ECB’s supervisory actions contributed to the decline in NPLs. This report also criticised aspects of our approach to credit risk, which I will return to later as I think it clearly illustrates some of the points I want to make today about the ECB’s supervisory philosophy.

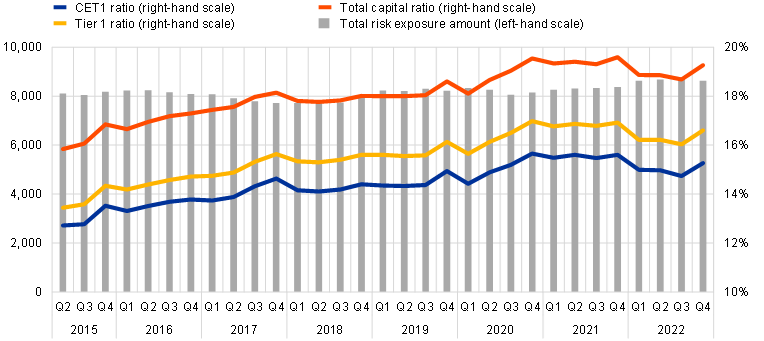

The second key change underpinning the resilience of the European banking sector is the increase in capital levels. European banks have gradually increased their balance sheet strength over the last ten years.

Chart 2

Capital ratios and their components by reference period

(EUR billions; percentages)

Source: ECB.

Today, the average CET1 capital ratio for significant banks in the euro area is 15.3%, which is a little higher than for US banks. But a simple comparison of risk-weighted capital ratios can be misleading, because the amount of capital banks ultimately need to maintain depends not only on the required ratios we set for them as supervisors, but also on their risk weights – in other words, the way they weight their assets according to the assets’ riskiness. My colleagues in ECB Banking Supervision recently analysed how much capital significant banks in the euro area would need if they were subject to the rules that apply here in the United States. For the global systemically important banks, they found that the requirements would be higher under the US rules, whereas for other euro area banks, they would be lower. This is partly because in Europe, legislators chose to apply the Basel standards to all banks, whereas here in the United States there is more differentiation between the rules that apply to the largest banks and those that apply to the smaller and medium-sized banks.

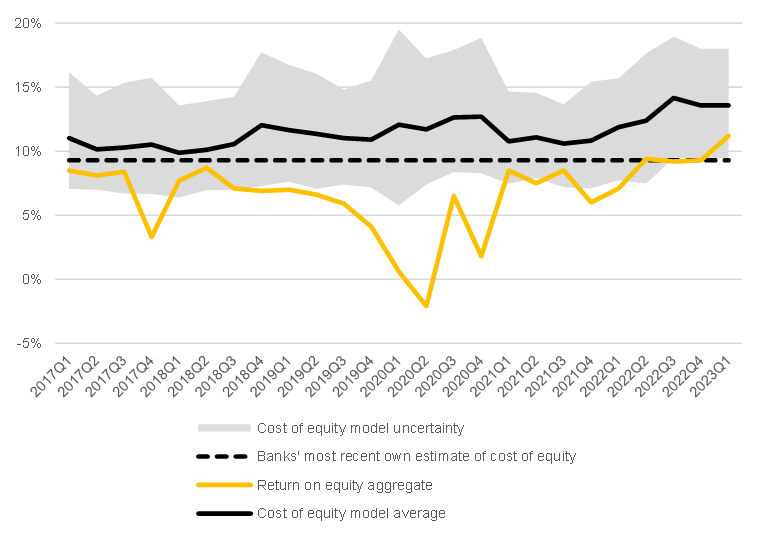

The third change that has made the European banking sector more resilient is the way in which European banks have adapted their business models. The major problem they were facing before the pandemic was one of profitability and valuations. Banks experienced a long period of very depressed valuations and return on equity that was well below the cost of equity. But in recent years, banks have been making efforts to refocus their business models, including through transactions affecting specific business lines – buying where they can specialise and gain market share and selling where they lack scale or expertise. And the current shift in the interest rate environment is boosting their net interest income, the backbone of profitability for the traditional business models that prevail in our banking sector. As a result, many banks are now credibly projecting a double-digit return on equity in the near future. And listed significant banks have in fact already achieved that, with an average return on equity of 11.2% in the first quarter of 2023, finally approaching the cost of equity.

Chart 3

Return on equity and cost of equity for a sample of 27 listed significant institutions

(percentages)

Sources: BankFocus, ECB and ECB calculations.

However, we must not be complacent just because the euro area banking sector managed to withstand this bout of turbulence. There are important lessons that euro area banks, and we as supervisors, can and should draw from recent events, and from the timely and deep analysis conducted by the US authorities.

Lessons for regulators and supervisors

It is important for supervisors to be self-critical. I commend my counterparts at the Federal Reserve and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) for their unflinchingly honest reports into the supervisory failings surrounding Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank.

At the ECB, we also commissioned a report from an independent group of experts in order to identify how we can improve our supervisory processes. I’d like to emphasise that we did so well before the recent turmoil, and it was not triggered by any particular event or failing, perceived or otherwise. Rather, the ECB’s Supervisory Board considered it important to have an independent, external group provide its perspective on our supervision to see where we can improve and to identify any blind spots we might have.

All of these reports – from the Federal Reserve, the FDIC and the independent expert group – reach similar conclusions on the importance of supervisors escalating their actions. The Fed found that, in the SVB case, supervisors continued to accumulate evidence of widespread weaknesses but delayed escalating supervisory action. Similarly, our independent expert group recommended that the ECB strengthen its follow-through process for qualitative measures by establishing a clear supervisory escalation ladder.

In my view, if we are to have a well-functioning escalation process, we need a clear risk prioritisation framework in place, and we need our supervision to have a strong focus on risk. This needs to bring together the findings of the bank’s internal audit function, off-site supervision and on-site inspections in order to prioritise what really needs to be fixed as a matter of urgency.

Risk prioritisation also needs to ensure there is a good interaction between the macro perspective on risks to financial stability and the microprudential view on individual banks. At the ECB, we aim to ensure this interaction through our process for identifying supervisory priorities, which is both top-down and bottom-up and includes horizon-scanning for risks that form the basis of the ECB’s supervisory activity for the subsequent three years.

Through this process we flagged the risks that rising interest rates would pose for the financial system, and we incorporated these risks into our supervisory work programme at the end of 2021. We made it a priority to ensure that supervised institutions were adequately prepared to manage the impact from interest rate and credit spread shocks and to adjust their risk assessment, mitigation and monitoring frameworks in a timely manner where needed. We also focused on banks’ medium-term funding strategies and placed greater emphasis on liquidity and funding risks. By the end of 2022, we had identified key outlier banks that were most vulnerable to the changes in interest rates and asked them to strengthen their management of interest rate risk.

While we need to factor in the macroprudential perspective, I also strongly believe that we need to remain focused on a bank-by-bank approach, taking into account the circumstances of each individual bank and tailoring our supervision accordingly. In fact, this is a legal requirement for us at the ECB, clearly spelt out in our founding statute, the SSM Regulation. But it is also essential in order to make our supervision effective in achieving the supervisory outcomes that we target.

This is where my views diverge from those of the European Court of Auditors and its report on the ECB’s approach to NPLs. The ECA made a number of valid points that we will work on to improve, and we are always open to criticism as I believe it helps us to be a better supervisor. But at the heart of the ECA’s recommendations is the suggestion that we gave banks with higher levels of NPLs too much time to comply with our coverage expectations and that we should have imposed capital requirements and accounting measures with greater automaticity, as a means of ensuring a level playing field for all banks. But in our view, this would have been counter-productive, depriving the banks of the capital space they needed for the sale and securitisation of NPLs that they did ultimately carry out. As we know, disposing of NPLs generates a loss, as the banks typically need to accept a price below the book value. That’s why we chose to calibrate our measures paying due consideration to the banks’ plans to sell or securitise portfolios of impaired assets, so as to reduce NPLs as quickly as possible.

In my view, it is important here not to confuse “equal treatment” with “the same treatment regardless of the circumstances”. Central to effective, risk-based supervision is the philosophy that supervisory measures should be tailored to the individual situation of each bank and proportionate to the issues they seek to address. In other words, differences in banks’ individual situations justify differences in supervisory treatment.

At the ECB, we are now sharply focused on strengthening the effectiveness of our supervisory processes by defining clear escalation ladders for our supervisors. To ensure that the banks remediate problems in a timely manner once they have been identified, it is important that we can expeditiously use all the instruments available to us. And equally as important, we are working to foster a culture that encourages supervisors to propose strong actions where they identify weaknesses.

One of the best papers on this topic that I always come back to is the IMF staff paper “The Making of Good Supervision: Learning to Say “No””, which was published in 2010.[3] As the authors of the paper recognise, good supervision should be intrusive, sceptical, proactive, comprehensive, adaptive and conclusive. It is about having both the ability and the willingness to act: supervisors must be willing and empowered to take timely and effective action. Developing a supervisory culture that promotes judgement and challenge is crucial here. We need to be unafraid to escalate where we detect deficiencies.

I would also like to suggest that an important lesson for supervision is to better understand the factors driving market assessments, which at times of turmoil may significantly depart from the traditional metrics used by supervisors.

In the recent turmoil, markets shifted rapidly from a balance sheet view to a mark-to-market view. This was the case for SVB, with investors focusing on unrealised losses on securities portfolios held at amortised cost. This reminded me of the case of Dexia in 2011, when, in the context of the euro area sovereign debt crisis, markets shifted very rapidly to assess the solvency of the bank based on the mark-to-market valuation of its sovereign exposures, irrespective of the accounting books where those exposures were allocated.

This can be understood as a kind of Gestalt shift, in which the market suddenly moves from one way of understanding reality to another, without any change in the underlying fundamentals. As the destructive market dynamics of this Gestalt shift play out, banks’ share prices drop as investors lose confidence in their future earnings potential. This is accompanied by moves in the credit default swap (CDS) price, creating an impression of increased default risk, which then drives fast deposit outflows – particularly destabilising where there is extensive reliance on uninsured deposit funding.

Euro area banks are generally less exposed to this kind of risk, as their unrealised losses are less material and they maintain buffers of liquid assets that include a large proportion of cash and central bank reserves. But as regulators and supervisors, we must be prepared for times when such destructive market dynamics take hold. To take one example, we have to be certain that banks can readily monetise their high-quality liquid assets at all times without suffering damaging fire-sale losses or incurring excessive haircuts, which can exacerbate negative investor sentiment. Ideally, this should be achieved via a regulatory approach which excludes assets held at amortised cost from the high-quality liquid assets used to comply with the liquidity coverage ratio requirement.

Governance is the unifying theme

So yes, supervisors need to be self-critical. But, in my view, it’s also important to turn the spotlight back onto the banks. Banks shouldn’t rely on the supervisor to identify risks before they crystallise. Ultimately, banks need to be doing that themselves.

When we look at the recent bank failures, in most cases we see a failure to manage risks, such as interest rate risk, liquidity risk and counterparty credit risk. In the end, this comes back to bad governance.

A lot has been written in recent months about the reasons for the banking turmoil in the United States and Switzerland.

But I would like to put forward what I see as the important common themes in these cases, which have perhaps been underplayed in much of the commentary. There is a prevailing narrative that the turbulence was essentially caused by a bumpy adjustment to a new monetary policy regime. This was certainly a trigger for SVB and to some extent the other US regional banks. But the trigger is not necessarily the underlying cause. And the situation at Credit Suisse points to a more important underlying common weakness that was also true for SVB – one of risk management and governance.

SVB and the other US regional banks that failed saw an abnormal growth in deposits throughout the period of low interest rates and the pandemic, which their risk management functions were unable to manage properly. Unrestrained growth strategies that were focused on accumulating deposits from venture capital and crypto-related customers, together with investment strategies that were heavily concentrated in longer-dated public securities, left these banks acutely vulnerable when interest rates rose and the negative outlook for the technology sectors and crypto business materialised. As the Federal Reserve’s report identified, SVB had “foundational and widespread managerial weaknesses” and its board “put short-run profits above effective risk management and often treated resolution of supervisory issues as a compliance exercise rather than a critical risk-management issue”.[4]

Credit Suisse, meanwhile, had been plagued by risk management and governance issues for years. In 2021, following the Greensill scandal, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) found that Credit Suisse had seriously breached its supervisory obligations with regard to risk management and organisational structures. The bank experienced significant losses that year as a result of its business relationship with the collapsed US family office Archegos Capital Management. A scathing independent report commissioned by Credit Suisse and published in July 2021 identified major failures in the risk management of its prime brokerage business, ranging from the risk appetite framework to the actual performance of the first and second lines of defence. And after very large losses in 2022, the bank acknowledged in its annual report in March 2023 that “the group’s internal control over financial reporting was not effective”.

The unifying theme in these cases is that markets identified the banks as outliers, primarily because their managers were failing to manage risks properly and their boards were unable to identify the issues in a timely manner and ensure that they were quickly remediated. Governance was at the root of the problem.

Clearly, this is not a new phenomenon. The banks that failed back in 2008 were those that were badly run. Consider Lehman Brothers, now a textbook example of risk management and corporate governance failures.

Conversely, banks that manage their risks well are better prepared to face a variety of adverse circumstances as their risk appetite is subject to closer scrutiny and control at all levels of the organisation.

As a general rule, well-run banks – in other words, banks with strong risk management and governance – don’t fail. In a macro environment in which investors and depositors are risk-averse, well-run banks can be islands of stability.

What do I mean when I refer to strong risk management and governance? I mean strong boards that not only facilitate the discussions with the management but also challenge the management, ask probing questions and promote a strong risk culture by setting appropriate incentives. Fostering that culture of transparency and constructive challenge is essential to ensuring that the risk profile remains consistent with the risk appetite. It is up to the boards to oversee and challenge the work of executives and control functions such as risk management and compliance. And boards need to have the right mix of members. There should be diverse perspectives, experience and knowledge. The idea is not that each board member needs to know everything. But collectively, the board must be able to provide comprehensive challenge across all the bank’s activities, risks and controls. Gender diversity also plays an important role.

The first line of defence, the frontline business units, should embed a strong risk culture and sound standards of conduct. The second line of defence, risk management and compliance – those who challenge the decisions taken in the business areas, and those who measure, monitor and mitigate risks – need to be independent and well-staffed, with direct access to the top. They need to work closely with the other lines of defence and, above all, they need to be taken seriously at all levels.

The ECB has been highlighting weaknesses in governance as a key supervisory priority for some time now. Governance is the area where we present most findings and recommendations in our SREP. And it is the area where remediation is not always as fast or as effective as we would like. For instance, we still see weaknesses in risk data aggregation and reporting, and we intend to increase our supervisory pressure here. Weaknesses in this area were singled out as a contributing factor in the collapse of Lehman Brothers, which had more than 200 entities worldwide and lacked the ability to quickly assess its global exposures or produce appropriate segmentation in data. Ten years after the Basel standards on risk data aggregation and reporting – BCBS 239 – were published, they are still far from being respected. Banks prefer to focus their investments on IT projects with an immediate commercial return, rather than fixing the basics of their risk management infrastructure.

There are also new emerging risks that require sound governance, especially those related to the digital transformation and the climate transition. I am looking forward to today’s sessions on operational resilience and climate risk, where I expect governance and risk management challenges will be discussed.

I think we should acknowledge that governance and business model sustainability are sometimes a difficult area for supervisors. There is a concern that we might be taking the steering wheel away from banks’ management and imposing solutions for choices that the management teams should remain responsible for. Indeed, the ECB has at times been criticised for being overly intrusive and interfering in the area of internal governance, which most banks see as the sancta sanctorum of their private autonomy in organising and directing their business. But when poor governance or an unsustainable business model puts the viability of a bank in jeopardy, supervisors need to be bold and drive change within a well-defined time frame. During the pandemic we focused our supervisory efforts on internal controls in the area of credit risk, as widespread public support measures, including payment moratoria, required extra efforts to identify early signs of deteriorating credit quality. This work was easily adapted in the light of the macroeconomic shock triggered by the unjustified war of aggression that Russia launched against Ukraine last year. We are now sharpening our supervisory scrutiny of digital strategies. A strong digital strategy has proven key to restoring profitability at many euro area banks. But when digital transformation is driven predominantly by a commercial perspective and overseen via a weak governance framework, with little attention to internal controls and risk management, it could prove a real problem. Supervisors should aim to hold a mirror up to banks, comparing them with their peers, sharing information on good market practices and requesting change whenever weaknesses in the governance of this transformation process could put the franchise at risk.

Conclusion

In conclusion, European banks are now stronger and increasingly profitable. This is thanks in part to the heavy lifting our supervisory teams have done over the last decade to make balance sheets stronger and business models more sustainable. But we are not, and should not become, complacent. We know that the risk environment is always changing. We too should practice what we preach. Supervision is most effective when there are strong internal processes to identify and measure risks, enabling clear priorities to be set for supervisory work. Supervisors should then be empowered to translate these high-level priorities into concrete supervisory initiatives, in the light of the specific challenges facing the banks they supervise, within a well-structured risk appetite framework. Consistency and effectiveness checks should be performed by an internal second line of defence, with an appropriate status and direct reporting to the board of the authority. And we should be accountable for the choices we make, explaining them clearly ex ante and accepting criticism and taking responsibility ex post. But supervisory authorities do not have perfect foresight and they cannot be expected to identify every danger facing every bank. So in the end, it is banks, not supervisors, that must take ownership of identifying and managing risks. And that means having robust governance and a sound risk culture, so that the pursuit of growth and profitability never comes before prudence.

Thank you very much for your attention.