Pia M. Orrenius, Ana Pranger, Madeline Zavodny and Isabel Dhillon

The current U.S. immigration surge is unprecedented. The influx flew under the radar for some time, dismissed simply as pent-up immigration from when the borders essentially closed during the pandemic. But this year’s Congressional Budget Office (CBO) budget and economic outlook brought new attention to the migrant inflow and its expected economic effects.

By incorporating previously unavailable data on migration along the southwest border into the government’s economic and fiscal outlook, the macroeconomic implications of such high levels of migration come into focus.

The labor force in 2033 will be larger by 5.2 million people, mostly because of higher net immigration, according to CBO estimates. As a result of the immigration surge, GDP will be higher by about $8.9 trillion and federal government tax revenues by $1.2 trillion over the 2024-34 period. Deficits will be lower by $900 billion.

No consensus on volume of immigration

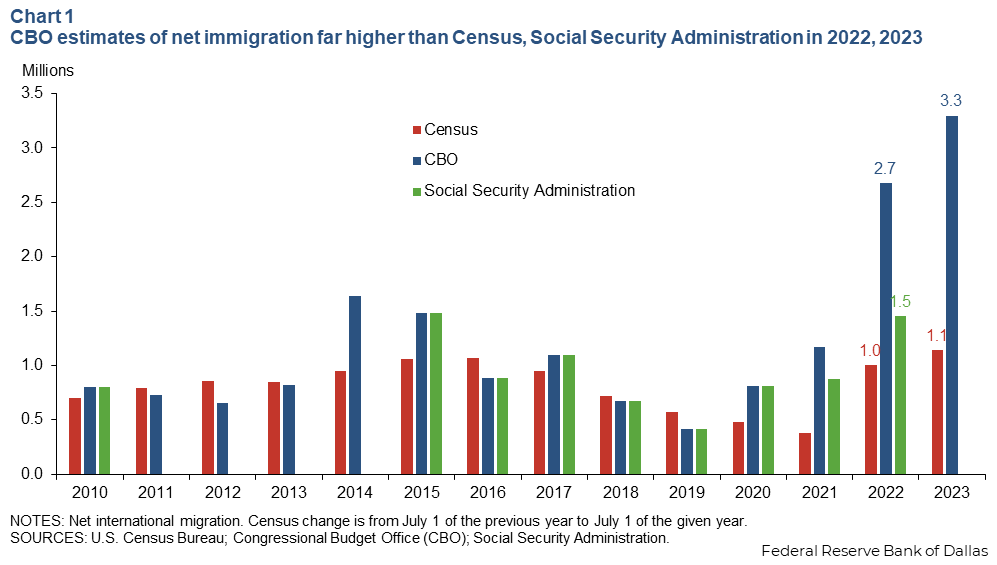

Government estimates of net immigration differ wildly. Census 2023 estimates (July to July) put net immigration at 1.1 million, far from CBO’s calendar-year 2023 estimate of 3.3 million (Chart 1). CBO similarly estimated a much higher net immigration number than other agencies in 2022—2.7 million.

Net immigration is the sum of individuals who enter the country minus those who leave. Entries can be permanent or temporary but exclude short-term visitors such as tourists. Entries can also be legal, when people come with U.S. government visas, or otherwise, such as humanitarian migrants (asylum seekers and, more recently, humanitarian parolees) and unauthorized immigrants.

CBO included real-time data on the number of border crossers allowed into the country, statistics that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) recently made available. Recently released 2023 data on immigrant work permits cast doubt on the lower immigration estimates in Chart 1 and are broadly supportive of CBO’s higher numbers.

Border surge sets record

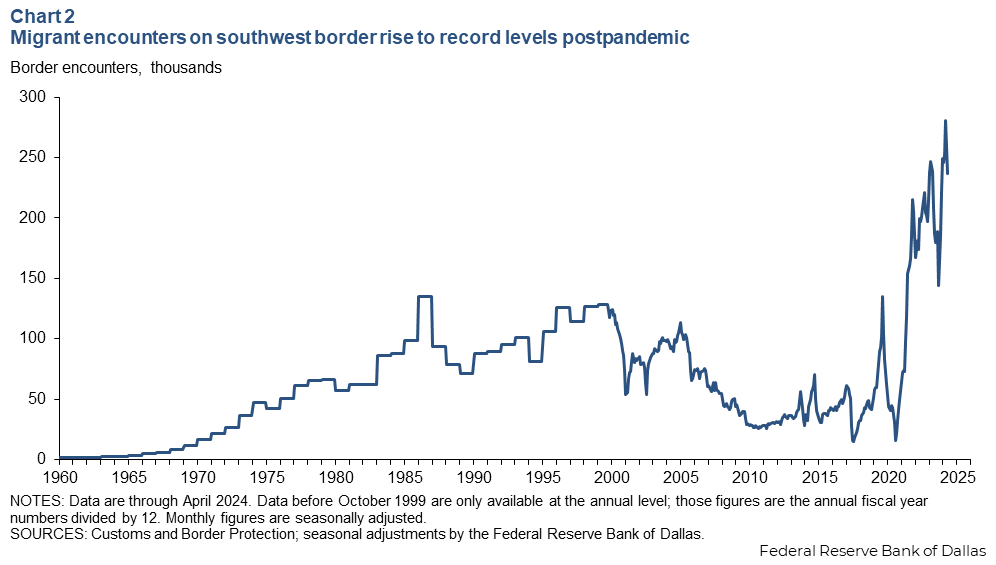

In 2023 alone, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) personnel encountered 2.54 million migrants at the southwest border (Chart 2). This is about the same as the 2.58 million migrants in 2022, a record year. This compares with the prepandemic annual average of 500,000 migrants.

Since the pandemic began in the U.S. in February 2020, CBP has recorded almost 8 million encounters at the southwest border, along with almost 2 million encounters at the northern border, coastal border and airports.

“Encounters,” previously known as apprehensions, include all people at and between ports of entry who are either stopped by the Border Patrol or who turn themselves in. In recent years, an increasing share of migrants simply approaches the Border Patrol and states an intention to seek asylum.

During the pandemic and until May 2023, some of these migrants, typically single adults, were immediately expelled under a provision known as Title 42, used to deny migrants entrance because of public health concerns related to COVID. However, more consideration was given to families and unaccompanied minors, and so even before the end of Title 42, the volume of migrants far exceeded available detention space. As a result, the majority of migrants has been paroled or otherwise released into the country to pursue asylum claims or other immigration pathways.

Notably, Border Patrol encounters do not include got-aways, or unauthorized immigrants, who escape the notice of Border Patrol while crossing or who are seen but not stopped. DHS publishes estimates of such migrants, although the figures differ significantly from estimates by demographers, at least in recent years.

Immigration policy, labor market shortages drive immigration

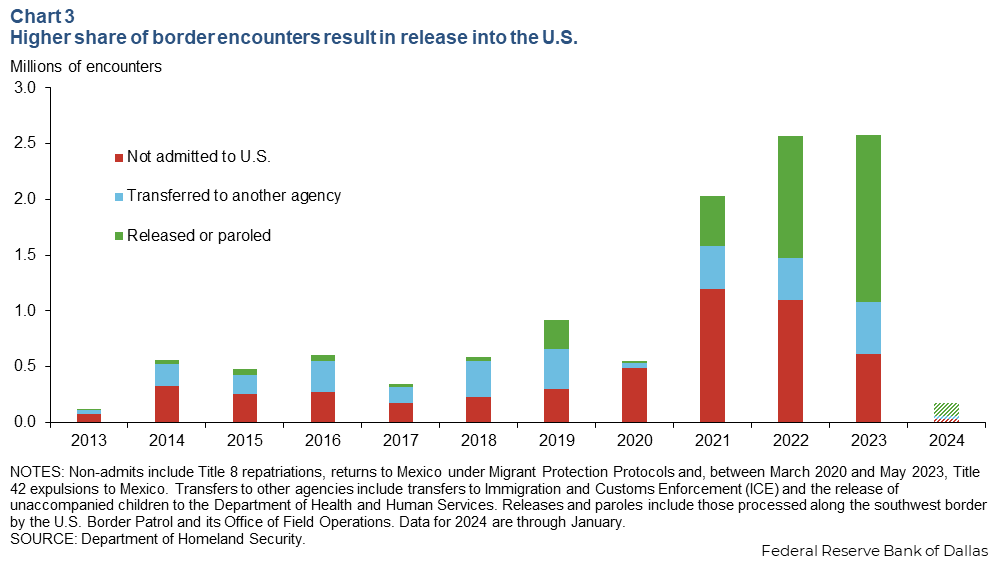

Though the number of encounters does not necessarily translate directly to the number of migrants admitted into the U.S., a smaller share is getting turned away than previously. In 2023, fewer than a quarter of encounters at the southwest U.S. border ended in migrants being refused entry into the U.S., and 58 percent of encounters resulted in migrants released or paroled into the interior (Chart 3).

This is a reversal from the previous nine years, when more than half of the 8.7 million migrants apprehended at the southern border were not admitted to the U.S., and less than a quarter were allowed in.

Harsh and deteriorating conditions in many Latin American and Caribbean nations, including Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela, prompted the U.S. government to expand programs such as humanitarian parole for those nations’ natives. Many migrants risk the trip to not only escape difficult circumstances, but also on the belief they can enter the United States under humanitarian provisions.

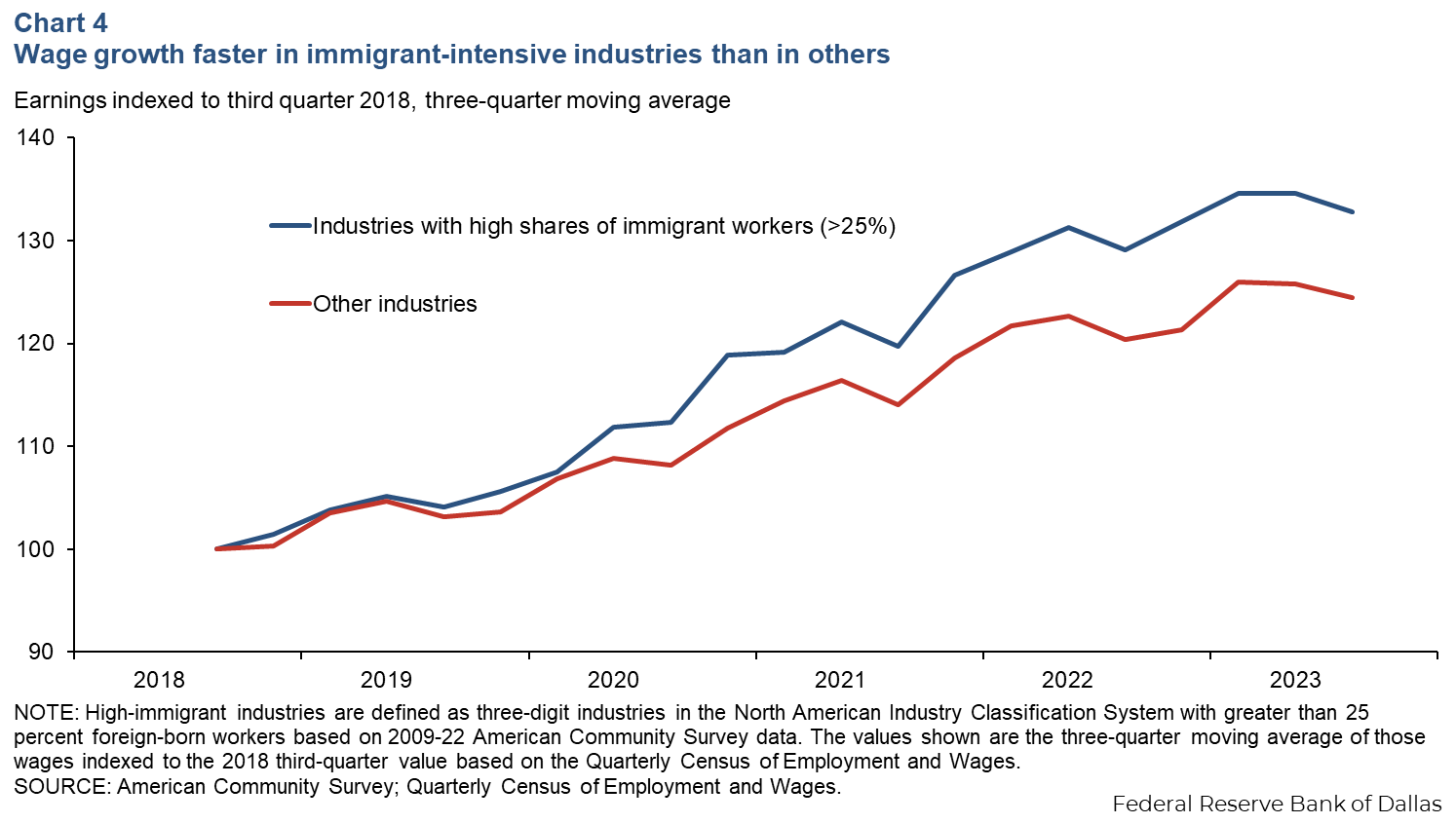

Another pull factor is the availability of work and rising wages. The postpandemic U.S. labor market was extremely tight, especially in sectors that tend to rely on immigrant labor. The job openings rate, or the number of job vacancies as a share of total employment in a sector, reached record highs in 2021 and 2022 for accommodation and food services, retail trade and health care and social assistance, among others.

Wages also rose faster in immigrant-intensive occupations and industries than in those that had a lower share of immigrants (Chart 4). Studies have shown that U.S. labor market conditions are among the main drivers of unauthorized immigration.

Influx has significant employment and GDP effects

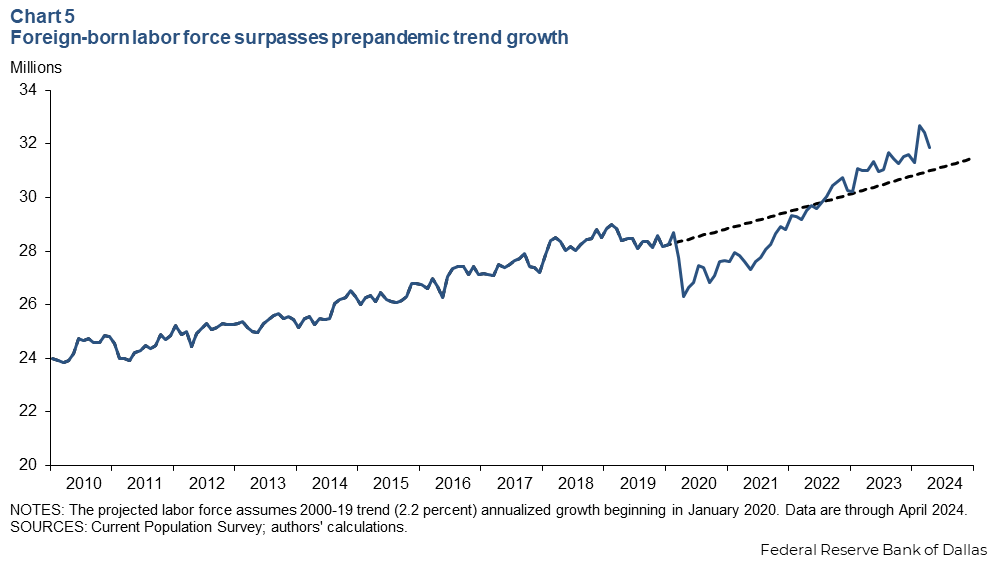

With this recent immigration wave, the foreign-born labor force has recovered completely from the pandemic drop, even exceeding what would have been expected absent the pandemic (Chart 5). The foreign-born labor force reached February 2020 levels in November 2021, and surpassed trend growth in August 2022, according to the Current Population Survey.

If the foreign-born labor force had grown at the 2000–19 trend rate of 2.2 percent per year starting in January 2020, it would have been smaller by almost 900,000 people in April 2024.

The jump in ready-to-work immigrants has boosted population, labor force and job growth in the postpandemic U.S. economy. Estimates from the Hamilton Project suggest higher immigration boosted payroll job growth by 70,000 jobs per month in 2022 and by 100,000 jobs per month in 2023 and so far in 2024. The upper end of the range of job growth has doubled to 200,000 from 100,000 jobs per month absent the surge of immigration.

It’s not unusual for immigration to account for high shares of job growth. Before the pandemic, from 2010 to 2019, the share of job growth attributable to immigration averaged 45 percent.

The jump in jobs, along with immigrants’ consumption of goods and services in the United States, also bolsters GDP growth. According to the Hamilton Project study, higher immigration has contributed about 0.1 percentage points to GDP growth annually in 2022 and 2023 and is projected to do so again in 2024.

The effect on inflation, meanwhile, could be neutral on average. Higher immigration represents a labor supply shock, which should be disinflationary. But immigrants are also consumers and add to aggregate demand. While certain sectors that extensively depend on immigrants should see costs and prices fall—for example, landscaping and child care—the population influx could put upward pressure on rents and house prices, particularly in the short run before new supply can be built.

Long-run outlook uncertain, but immigration needed for growth

The immigration surge has surprised many, and not everyone agrees with the CBO numbers. But household survey data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) are consistent with CBO estimates of immigration in 2023.

According to the CPS, the foreign-born population rose by 2.5 million from December 2022 to December 2023, even as we estimate about 500,000 immigrants died. These data points are consistent with a net immigrant inflow of at least 3 million over the year. The doubts about CBO’s large number involve problems with encounter data (it measures events, not individuals), debates about migrant return rates and criticism of the household survey (whether it overcounts or undercounts immigrants).

CBO’s immigration projections are even more uncertain, with expected net immigration of 3.3 million in 2024, 2.6 million in 2025, 1.6 million in 2026 and a return to the historical average 1.1 million in 2027–33.

It’s unclear what factors drive these transitions. Potential changes in U.S. immigration policy, such as the Biden administration’s recent executive action limiting the entry of some migrants, or an economic downturn could result in gradual normalization of immigration at the border. Even so, many of the migrants who arrived in recent years will want to stay in the United States.

Asylum approval rates have risen since 2020 but reflect cases filed in years prior. It’s impossible to know what approval rates will be for those who filed their claims more recently. Humanitarian parolees, in contrast, are supposed to return to their home countries after two years.

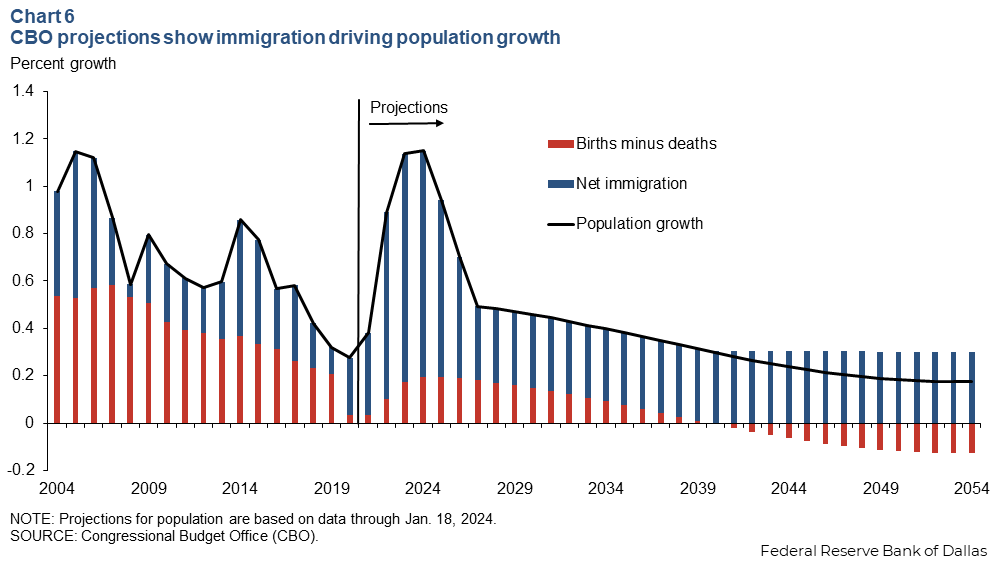

If immigration normalizes, it will return to rates that are insufficient to sustain the type of economic growth the U.S. is accustomed to. The nation is in a sort of demographic autumn, and winter is coming. The retirement of the baby boomers and overall aging of the workforce, as well as low and falling birth rates mean population growth will become entirely dependent on immigration by 2040, as deaths of U.S.-born will outpace births (Chart 6).

Because economic growth depends on labor, capital and productivity, growth in these factors will set the speed limit of the economy. While technological advances and incentives for investment will contribute to productivity growth, immigration will be vital to propping up labor force growth.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.