8

By Hamish Peacocke, Chief Capital Officer and Co-Founder, Perenna

By Hamish Peacocke, Chief Capital Officer and Co-Founder, Perenna

Covered bonds (CBs) have long been a feature of European mortgage funding. In contrast, the United Kingdom has historically relied on deposit-based retail funding. At a time when UK housing affordability and homeownership are challenging, interest rates are high, and inflation remains stubborn, a strong case should be made for the UK to embrace a new bank-funding model—in the interests of both homeowners and institutional investors seeking long-term, stable income.

Perenna is the UK’s first covered-bond bank. Unlike traditional banks, we don’t take retail deposits, and we fund our mortgage lending through the issuance of covered bonds, of which buyers are real-money investors. Whilst we are a private initiative, our model strongly parallels the US government-agency institutions Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association, or FNMA) and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, or FHLMC).

By shedding light on the CB model, its prevalence in Europe and its differences from other mortgage-funding approaches in the UK, we will explore the advantages of CBs and their roles in providing stability, flexibility and consumer empowerment.

Long-dated funding markets are well developed across Europe

The CB model has deep roots in Europe. Several countries, including Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany, use it as a major financing tool. Denmark, for example, has employed CBs for more than a century and is widely considered the first country to adopt them.

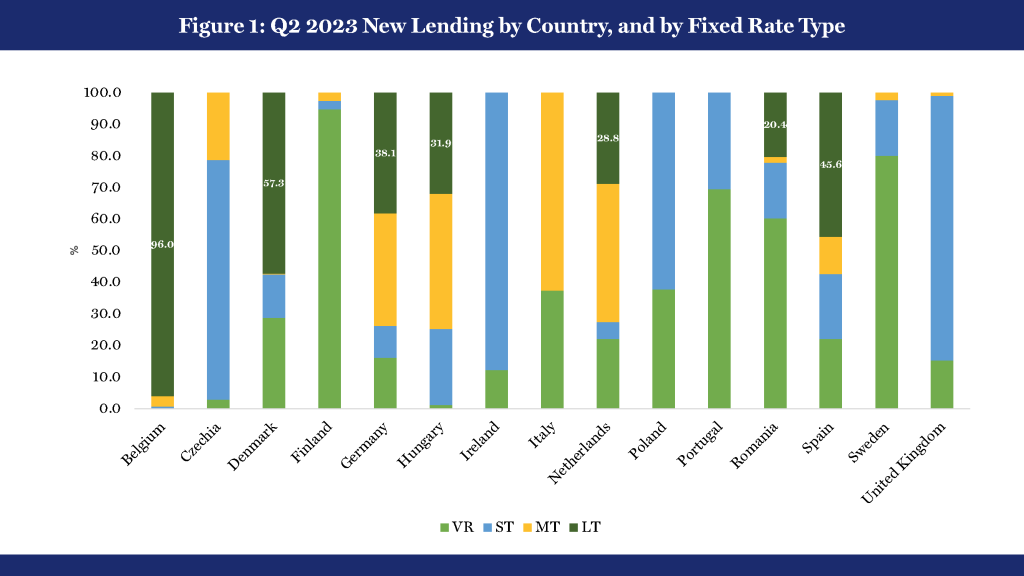

As a result, mortgage offerings across Europe are more diverse, offering consumers far more product choices (see Figure 1 at the end of the article).

The UK paradigm

Unlike its European counterparts, the UK relies largely on short-term retail deposits to fund its mortgage lending. Because of this, product design and consumer choice are limited.

UK mortgages are largely homogenous: short-term, fixed-rate deals before the borrower is placed at a much higher standard variable rate (SVR) unless they remortgage. This model has become ingrained in the culture and economics of the UK’s housing market. Borrowers secure a mortgage, enjoy their short-term teaser deals and then must remortgage after a couple of years to avoid paying significantly higher amounts. Two- and five-year fixes have traditionally been the norm.

With interest rates rising significantly over the last few years, many have begun to realise the risks associated with UK mortgage products. By the end of 2024, more than 1.6 million homeowners will reach the end of their fixed-term deals and suffer significant increases in their monthly repayments due to the designs of their products.

This isn’t right. Long-term, fixed-rate mortgages are being seriously considered and discussed by both the Labour and Conservative parties ahead of the next general election later this year. UK borrowers would be protected from interest-rate vagaries, as their peers are in the United States and Europe. However, a new type of financial infrastructure is required for this to flourish in the UK.

A bank model from which you can’t run away

Another feature of the CB model is its resilience. Deposit-funded banks are made vulnerable by the ease with which depositors can withdraw their funds. This means that when things go wrong, they can go very wrong. Rumours and concerns about a bank’s long-term stability can spread like wildfire. Deposit holders can rapidly transfer out their cash in large swathes, leaving their banks at risk of collapse unless other institutions or regulators step in. We only need to look at Northern Rock during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) or, more recently, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

The CB model, on the other hand, is long-term and matched, ensuring a stable and balanced banking system, reducing asset-liability mismatches and eliminating bank-run risks. The CBs’ safety and reliability are key attributes reinforced by high ratings, government support and FCA (Financial Conduct Authority)-specific regulations.

Facilitating access to homeownership

In addition, a CB model can provide tailored solutions for a whole range of homeowners and demographics with differing needs instead of a one-product-fits-all approach.

An increased product range not only fosters stability but also empowers consumers. By offering them longer-term, fixed-rate products, borrowers gain flexibility without sacrificing financial security. Eliminating short-term interest-rate risks and fluctuations allows lenders to provide mortgages based on genuine affordability rather than interest-rate stress tests and, in some cases, unlock 25 to 30 percent more borrowing capacity for homebuyers. For many, it means the difference between buying a home or not. Giving people more options and buying power reduces the steps on the housing ladder.

Perenna intends to use the CB model to bring back UK home ownership to the levels at which it used to be, peaking at around 70 percent in 2004. As Fannie Mae did 70 years ago, we want to transform homeownership by driving the wider adoption of long-term, fixed-rate mortgages in the UK.

Addressing demographic challenges: The golden generation

The UK banks that impose restrictive age limits typically underserve those in or approaching retirement. The CB model addresses those current limitations on mortgage access. From a risk perspective, the golden generation is one of the best borrower groups; many have fixed pension incomes and large amounts of equity in their properties. People should have the ability and opportunity to borrow into retirement. As CBs remove interest-rate risk from the borrower, lenders can responsibly extend mortgages to this demographic, enabling them to support their retirements, assist their children in securing deposits and maintain their financial resilience. Nothing is more perfect than a fixed mortgage payment against a fixed income.

Finding parallels in the US mortgage market’s structure

The CB model parallels Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which issue debt to real-money investors, backed by a pool of long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. Whilst these US agencies apply a securitisation model, the Perenna model issues covered bonds, offering recourses to both the underlying asset pool and the issuing bank.

Unlike mortgages in the US, however, Perenna’s CB model gives borrowers flexibility—the mortgage is portable and transferrable. Homeowners are not locked into their homes. If they want to change jobs, they can; if they want to move home, they can—without long-term, early-repayment charges. In Perenna’s case, these are removed after five years. It’s about giving the same flexibility as a short-term mortgage fix but for a far longer period.

The CB model paves the way for international expansion as well. Other countries, such as Canada and Australia, have similar mortgage-market dynamics to the UK’s and would benefit from adopting this model.

Environmental impacts: catalysts for retrofitting

Beyond financial considerations, CBs also play a pivotal role in addressing environmental challenges, especially in markets with energy-inefficient housing stocks. After recognising the urgent need for retrofitting properties, the CB model becomes a crucial tool.

According to the Climate Change Committee (CCC), 29 million homes in the UK must be upgraded to low-carbon heating systems by 2050 to reduce emissions enough to hit net-zero targets. The CCC has estimated that an investment of about £250 billion will be needed to decarbonise homes fully by 2050. By funding energy-efficient renovations and projects, lenders contribute to reducing emissions and creating a more sustainable UK housing stock.

This innovative approach extends to financial benefits for borrowers. By spreading the costs of retrofitting over the mortgage term, homeowners experience instant cash-flow benefits, making environmentally conscious decisions financially viable.

The benefits for institutional investors

For real-money investors, CBs are a compelling asset. Their primary appeal lies in their fixed-repayment profiles, which nicely match the long-term, fixed liabilities of many pension funds and insurance companies. For instance, life insurers, who are responsible for paying out policies over decades, seek investments that align with the extended nature of their financial obligations.

For these investors, their resilience and security set CB assets apart. Investors receive dual recourse to both the issuing bank and a diversified pool of prime mortgage loans, providing even greater security than mortgage-backed securities. Investors also receive preferential capital and liquidity treatment compared to mortgage-backed securities.

A vision for the future

Crises share a common thread with the emergence of new financial infrastructures—for example, the US with the Great Depression, Denmark with the Copenhagen Fire of 1728 and Germany with the Seven Years’ War, which created the Pfandbrief banks. The UK faces major issues, and in response, a new model is emerging: the UK’s first covered-bond bank.

Reshaping the UK mortgage market is a huge challenge, something Perenna was designed to do. Facilitating equitable and sustainable access to homeownership is one of Perenna’s core tenets. Creating a nation of happy homeowners is in our DNA.

Key: Variable rate (up to 1Y initial rate fixation), short-term fixed (1Y-5Y initial rate fixation), medium-term fixed (5Y-10Y initial rate fixation), long-term fixed (over 10Y initial rate fixation).

Reference: EMF Q2 2023 Quarterly Review of European Mortgage Markets, Eric Hüllen, European Mortgage Federation—European Covered Bond Council.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hamish Peacocke is Founder and Chief Capital Officer of Perenna, focused on raising equity and debt. He has more than 20 years of experience in financial markets, working on various mortgage-related projects. In his career, he has worked for organisations such as Credit Suisse, BNP Paribas and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer.