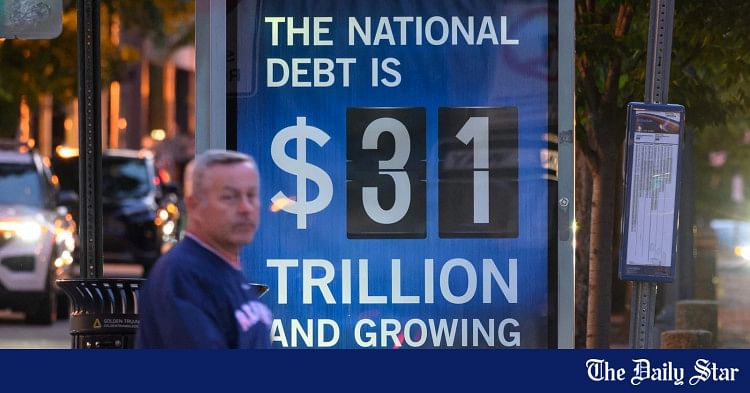

For over two months, there has been speculation in the US – and, one might even say, across the globe – about whether the Biden administration and the US House of Representatives will reach a deal to raise the debt ceiling. The current debt ceiling is $31.46 trillion. Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen announced on May 1 that unless the US Congress raises the ceiling, the US government could run out of cash as early as June 1.

For the rest of the world, the negotiations in the US capital between the opposing teams (led by President Biden and Speaker McCarthy) have been a lesson on economics, politics, and the latest state of the geopolitical power balance. Biden, who had planned an extended trip to Japan, Papua New Guinea, and Australia to shore up the anti-Russian alliance and to counter growing Chinese influence in the Pacific, cut short the sojourn and rushed back home after the G7 summit for the budget talks.

The moral of the story so far is: domestic financial stability and the president’s credibility are of greater urgency and rightly deserve a higher priority than fighting Russia and isolating China.

For those who might have lost track of the negotiations and are wondering how the crazy US-American reality show arrived at the current state of affairs, let me offer a recap.

Every few years, the US government goes to Congress to seek approval to spend more money than it earns. In 1939, Congress passed a law establishing the debt ceiling at an initial limit of $65 billion. Since 1960, the US has either raised, extended, or revised the debt limit 78 separate times and has always succeeded in raising the debt ceiling.

The problem now is two-fold. The House of Representatives is under the control of the Republican Party, which took over in January on the promise that it would enact legislation to curtail the Federal Budget. However, the president, a Democrat, won the 2020 elections and has since then gone on a mission to spend more money on green energy, the Ukraine War and various social programmes. The Republicans are using the debt crisis and the June 1 deadline to extract some concessions from the Democrats, particularly stricter work requirements for social safety net programmes, and cuts in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) spending measures.

To avoid a default, the government could bypass the speaker and work with centrist Republicans to secure the 217 votes needed to get a pro-Democrat bill. Failing that, it could keep on borrowing and ignore the debt ceiling under the umbrage of the 14th Amendment.

Interestingly, the House of Representatives proactively passed a bill on April 26 to raise the debt ceiling, and this was approved 217 to 215 along party lines. The Limit, Save, and Grow Act of 2023 would suspend the debt limit through March 31, 2024, or by $1.5 trillion, whichever comes first. The legislation would raise the debt ceiling in exchange for freezing spending at last year’s levels for a decade – a nearly 14 percent cut – and cap spending growth at one percent. Biden and the Democrats have already expressed their opposition to this bill, but the Republican initiative has put the Democrats in a tight spot.

So, what happens if Congress and the president fail to agree to raise the debt ceiling? First, the US government could default and postpone payments on some of its obligations. While the media has focused on debt servicing, the government could reduce its other discretionary expenditures, including social security, salaries, Medicare and various commitments.

Secondly, a default would have a major impact on the financial market and the US economy. Brookings Institution analysts Wendy Edelberg and Louise Sheiner recently argued that, “Worsening expectations regarding a possible default would make significant disruptions in financial markets increasingly probable” and that “such financial market disruptions would very likely be coupled with declines in the price of equities, a loss of consumer and business confidence, and a contraction in access to private credit markets.”

The United States has the highest credit rating from two of the three major rating agencies. But if it defaults on its debt, the agencies have vowed to downgrade its rating.

Even if the two sides reach a deal after Memorial Day weekend, some damage has already been done.

To avoid a default, the government could bypass the speaker and work with centrist Republicans to secure the 217 votes needed to get a pro-Democrat bill. Failing that, it could keep on borrowing and ignore the debt ceiling under the umbrage of the 14th Amendment. However, as legal scholars have pointed out, while the 14th Amendment bars debt defaults, it does not authorise the president to borrow money to pay for social security or welfare.

So, when the president and the congressional leaders sit down next week, we expect some progress.

There are three lessons. First, as Professor Tomas Philipson of the University of Chicago and former acting chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisors wrote in an op-ed, “Great damage is done by the debt negotiations, which are part of a persistent pattern in which the government creates large, destabilising market risks.”

Second, the outgoing World Bank President David Malpass criticised the governments for borrowing from the market, leading to an explosion of public debts, and crowding out private sector growth.

Third, as the Wall Street Journal reports, even once the debt crisis is resolved, the financial market will experience further aftershocks, especially the deposit-hungry banks.

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist and works for Change Healthcare, Inc, an information technology company. He also serves as senior research fellow at the US-based International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI).