Speech by Claudia Buch, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, House of the Euro, Brussels

Brussels, 12 February 2024

It is a great honour to speak to you today. The new year is well underway, but let me still wish you all the best for 2024.

Many Europeans look into the new year with concerns about the future. Immigration, the Russian war against Ukraine, geopolitics, inflation and climate change are mentioned as key concerns in recent Eurobarometer surveys.[1]

We indeed live in a period of high uncertainty, characterised by “shifts and breaks”, as President Lagarde said last year.[2] Our economies and societies have been hit by several shocks in the past few years. There is high uncertainty surrounding the conjunctural outlook and, more fundamentally, the structural changes that lie ahead. Geopolitical risks, climate change, demographic trends and digitalisation are forcing us to adjust the way we produce and consume.

This uncertainty affects banks. In the short-term, higher interest rates have boosted their profitability. European banks have weathered recent storms thanks both to their own resilience and to the significant fiscal and monetary support that mitigated the impact of the recent shocks. However, in the longer term, banks will not be immune to risks and unexpected events. The currently good level of profitability provides an opportunity to build buffers to cushion shocks.

At the same time, a stable banking system is crucial for managing risks and promoting welfare.

Ensuring that the banks remain resilient is thus the central objective of European banking supervision. Resilience means that banks can absorb shocks – that they may bend under stress, but that they won’t fall.

The banking union gives us the relevant tools and powers. It is one of Europe’s major achievements. It was, ten years ago, the right response to the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis. With the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Board, we have strong frameworks and institutions to safeguard the stability of banks and to deal with stress events.

The stability of the EU framework is indeed appreciated by its citizens, despite the anti-EU rhetoric that we often hear. Surveys show that most look to the EU as a source of stability and are optimistic about the future of Europe.[3]

The achievements of the SSM during its first ten years are a strong foundation for our future work. We closely cooperate within the system, we apply the same standards across all supervised banks, and risks have been reduced. This would not have been possible without the trust that has been forged between supervisors across Europe.

But we should not stop here. Complacency is not an option. I see three main areas of focus for European banking supervision.

First, we need to adapt our supervision to the new environment. Heightened macroeconomic and geopolitical risks coupled with changes in the competitive environment leave banks exposed to new risks. This requires close attention, and it is one of our supervisory priorities.

Second, we need to enhance supervisory effectiveness. This means focusing attention on relevant risks and following up on supervisory findings.

Third, we need to continuously and transparently connect with our stakeholders. This is at the centre of activities to mark the SSM’s tenth anniversary. We are planning several initiatives to bring us closer to the EU citizens we serve and to engage with policymakers. It is no coincidence that I am giving my first speech here in Brussels, the heart of Europe and the home of the European legislator.

The first decade of European banking supervision – increasing resilience and building trust

To highlight the remarkable achievements of European banking supervision, I would like to recall how we have increased resilience and built trust over the past ten years.

We have created strong pan-European supervisory teams. When Danièle Nouy became the first Chair of the Supervisory Board in 2014, she started with a small team. When my predecessor Andrea Enria finished his term at the end of last year, ECB Banking Supervision had over 1,500 members of staff. And the SSM community is much larger. The national supervisory authorities contribute around 90% of the staff for on-site inspections, and many national supervisors cooperate closely with the ECB supervisors in Joint Supervisory Teams. We also have lots of training and exchange programmes that foster collaboration at every level.

Without this close cooperation, we would have been unable to carry out our tasks. Our teams benefit from sharing experiences across Europe.

We have established common supervisory standards. In 2014 we did not have a common supervisory approach. Since then, we have harmonised European banking supervision across participating countries through guides and supervisory policy documents. We have consistently applied common supervisory standards to banks’ internal models and their practices related to non-performing loans (NPLs).[4]

Over the past decade, the resilience of the EU banking sector has increased.

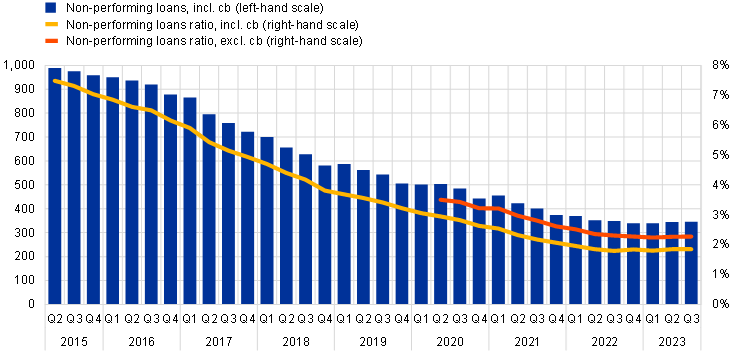

Non-performing loans, once the bane of the European banking system, have fallen significantly. The NPL ratio of significant banks declined from over 7% in 2015 to less than 2% in 2023 (Chart 1).[5] Our guidance on NPLs has been a driving factor, as has economic growth.

Chart 1

Non-performing loans

(left-hand scale: EUR billions; right-hand scale: percentages)

Source: ECB supervisory banking statistics.

Note: “cb” refers to cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits.

Capital and liquidity levels are much higher today than a decade ago. The aggregate Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio, which is based on banks’ risk weighted assets, increased from 12.7% in 2015 to 15.6% 2023. The leverage ratio, which is based on banks’ total assets, has increased by less, and it was only slightly higher in 2023 at 5.6% than its 2016 level of 5.3% (Chart 2). The liquidity coverage ratio increased from 138% to 158% over the same period.

During the initial phase of European banking supervision, supervised banks thus de-risked their balance sheets and increased their capital levels. But given the prolonged low interest rate environment, they also became more exposed to an abrupt change in interest rates. This vulnerability has been addressed by our supervisory priorities since 2021.

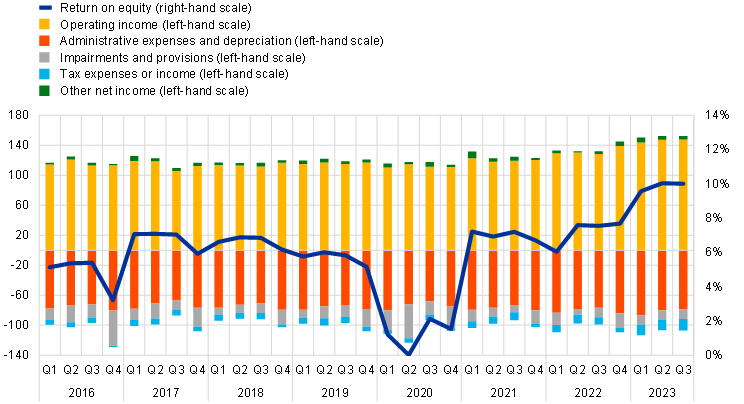

Meanwhile, what would have been an adverse interest rate scenario in the past has in fact already materialised. Between July 2022 and September 2023, the ECB responded to higher inflation by raising interest rates by a cumulative 450 basis points[6] – the fastest rate hiking cycle in the history of the euro area. In the short-term, higher interest rates have contributed to higher profitability and market valuations of banks (Chart 3). Valuation losses on securities held at book value have been contained.[7]

Chart 3

Return on equity and composition of net profit and loss

(left-hand scale: EUR billions; right-hand scale: percentages)

Source: ECB supervisory banking statistics.

The longer-term effects of higher interest rates are more uncertain. It remains to be seen how higher interest rates affect credit losses and depositor behaviour. So far, the pass-through of higher interest rates to deposits has been slower than in the past. At the same time, the digitalisation of business models could lead to faster deposit withdrawals in response to news.

There is a clear message here: banks should remain highly focused on managing risks and enhancing the resilience and sustainability of their business models.

The second decade of European banking supervision – adapting to a new environment

The second decade of European banking supervision will be one of adaptation. Many of the issues dominating today’s headlines were inconceivable a decade ago. This underscores the need for banks not only to respond to emerging risks, but to anticipate them too. And it is also incumbent upon supervisors to be agile and prudent and to adopt a critical mindset. The SSM supervisory priorities thus reflect two key trends.

Heightened macroeconomic and geopolitical risks

The first trend is heightened macroeconomic and geopolitical risks, including climate-related and environmental risks. Interest rates and energy prices have already increased, growth projections have been revised downwards, climate-related risks are becoming increasingly visible, and the number of cyber attacks has risen.

Many of these changes are structural rather than temporary, and they require adjustments at the firm and sector level. Corporate insolvencies and credit risk may increase. Highly indebted borrowers with weak business models may come under pressure.

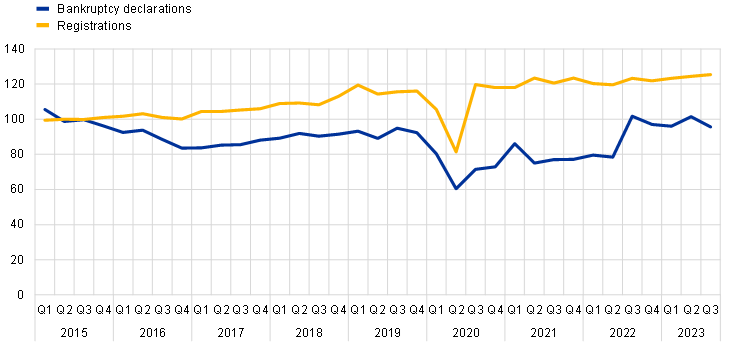

Yet, assessing future credit risks is difficult. Low default rates observed in recent years might not be representative of future risks, so they should be treated with caution. Even at the height of the pandemic in 2020, when European GDP contracted by 6%,[8] corporate insolvencies did not increase, and actually declined in many countries thanks to the fiscal measures put in place (Chart 4).[9] In the future though, fiscal support for stressed corporates is likely to be more constrained.

Chart 4

Quarterly registrations of new business and declarations of bankruptcies in the EU between 2015 and 2023

(index: Q1 2015 = 100)

Source: Eurostat.

Note: Data refer to the EU27 countries from 2020.

There are already clear indications that the asset quality of significant institutions is beginning to deteriorate. Up to the end of 2022, there had been 32 almost uninterrupted quarters of declining NPLs.[10] Since 2023, however, NPLs have increased modestly, albeit remaining at low levels.[11]

In addition, many new risks are difficult to quantify. How can we assess the likelihood of geopolitical risks materialising? What will the impact be on an individual bank? How should we quantify the transition and physical risks of climate change?

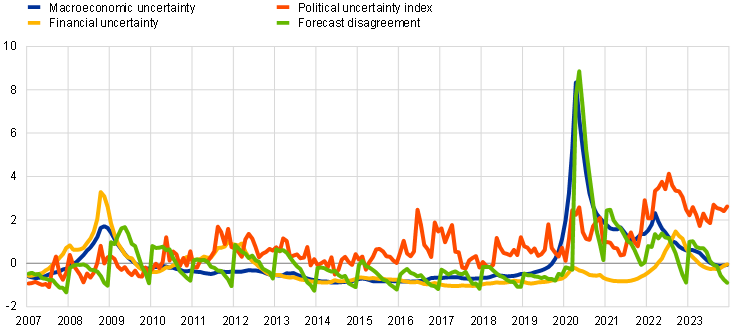

What’s more, financial data do not adequately signal heightened levels of political uncertainty (Chart 5). This could lead to unexpected market reactions, triggered by adverse shocks. Liquidity risk management thus requires careful attention, not least because the shift from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening affects the market footprint of central banks.[12]

Chart 5

Measures of uncertainty in the euro area

(standard deviation)

Sources: Eurostat, Haver and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: All measures of uncertainty are standardised to mean zero and unit standard deviation over the full horizon starting in June 1991. A value of 2 should be read as meaning that the uncertainty measure exceeds its historical average level by two standard deviations.

This high degree of uncertainty cannot be captured by classical risk models.[13] Models will remain the backbone of our work. But a holistic view of the new risk landscape requires the use of scenarios, improvements in data and measurement, and a close interaction between bank-level and macro-level analysis.

How do banks deal with heightened uncertainty? SSM surveys show that new risks are insufficiently integrated in banks’ risk management processes. Many banks use prudential overlays because past data do not allow new risk drivers to be accurately modelled. This is good news. But we also found shortcomings: banks use a variety of approaches, many of which lack the required risk sensitivity. We therefore called for improvements and are now re-running our review to ensure compliance. Let me thus use this opportunity to remind banks and auditors to adhere to best practices on novel risks and overlays.[14]

Our work also shows that remaining gaps related to risk data aggregation need to be closed. For many years now, we have identified weaknesses in banks’ risk information systems. Banks’ decisions may thus be based on flawed or incomplete information. Investing in up-to-date information systems is of course, costly. But these systems are indispensable, particularly in view of the ongoing digitalisation of the financial services industry. Therefore, we are strengthening our efforts to ensure that long-standing shortcomings are remediated.[15]

We are also focusing attention on credit risks. Aggregate macroeconomic developments may hide relevant shifts in banks’ credit portfolios. Some firms may deal quite well with the effects of higher energy prices or a disruption of global value chains – others may not. This firm-level exposure matters for banks. That’s why we have focused our recent work on vulnerable sectors such as commercial real estate or SME borrowers at risk of default.

Digitalisation and the competitive landscape

Digitalisation and changes in the competitive landscape is the second main trend. Structural change thus also characterises the banking sector itself. Non-banks have increased their market share of credit granted to euro area non-financial corporates from 15% in 2008 to 27% in September 2023.[16]

In addition, new digital business models promise faster and more efficient financial services. Banks may benefit from upgrading their own technologies, but they also face fiercer competition and potential disruption of their value chains.

Yet, increased competition can weaken financial stability.[17] Higher competitive pressure tends to supress banks’ margins. This could prompt banks to loosen their underwriting standards, to accumulate riskier assets, and to become more vulnerable to adverse shocks.

So, our response is not to restrict competition but to ensure that negative side effects are mitigated and that banks are resilient.

One negative side effect can be more volatile deposits. Deposit withdrawals from distressed banks have increased in the recent past, as demonstrated during the US regional banking crisis in March 2023. We will thus focus on funding and liquidity risks in this new environment, including through targeted reviews of funding plans.

Digitalisation may also increase banks’ vulnerability to IT and cyber risks. Banks have become more dependent on outsourcing and third-party services, including for critical functions. At the same time, the market for IT services is highly concentrated and vulnerable to geopolitical risks.

We are responding to this heightened vulnerability. We conduct targeted reviews and inspections, and we are currently preparing a cyber resilience stress test on 109 banks under our direct supervision. The exercise will assess how banks respond to and recover from a cyberattack. The main findings will be communicated in the summer of 2024.

Taking action

Once we have identified vulnerabilities and insufficient risk management, we need to take action. We must ensure that banks are well governed and that they have sufficient capital and liquidity buffers.

Past episodes of bank distress have shown that capital and liquidity ratios are not everything. Distressed banks often met regulatory requirements until very late. But they performed poorly in terms of governance and risk management, often well before the actual stress events occurred.[18] This is why we pay close attention to banks’ internal governance mechanisms and the long-term sustainability of their business models. Banks need strategic steering to adequately assess, control and manage risks, especially in an uncertain environment.

But capital and liquidity have certainly not become less important. Banks need to be well-capitalised to deal with unforeseen events. It is ultimately only capital that can absorb adverse shocks and allow banks to continue lending in times of stress. Clearly, the better capitalised a bank is, the less detrimental are the implications of poor risk management – for the bank itself and for the financial system.

In addition, banks often fail when poor risk management is exposed by adverse macroeconomic shocks. We thus need close cooperation between micro- and macroprudential supervision. Strong microprudential supervision is the foundation for financial stability – but as supervisors we cannot address systemic risk by concentrating on individual institutions alone. That is why strong macroprudential action is needed to address systemic risks in a timely and comprehensive manner. Clearly, the effectiveness of supervision is not only based on our microprudential Pillar 2 decisions but also on the macroprudential tasks and powers conferred upon us by the law.

Generally, if we identify weaknesses, we need to use our supervisory tools in a timely and effective manner. The SSM Regulation equips us with a comprehensive supervisory toolkit. We need to use the full range of these tools to foster the necessary improvements in banks.

In the area of climate-related and environmental risks, we have already established clear supervisory guidance and follow-up procedures. This year, we will intensify the use of escalation mechanisms, possibly extending to enforcement actions and sanctions, to ensure supervisory findings are addressed and deficiencies are remedied.[19]

Enhancing supervisory efficiency and effectiveness will free up resources to focus on emerging risks. That is why I am committed to concluding the reform of the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP), which Andrea Enria initiated based on independent expert advice[20]. We have already followed a new multi-year assessment framework for the 2023 SREP cycle, aligning the intensity of our supervision with each bank’s specific vulnerabilities and our overarching supervisory goals. We are also reviewing our internal processes in time for the 2025 cycle.

This is all supported by the SSM’s digital agenda. Digital tools reduce the time spent on routine tasks and provide useful information. Since 2020 we have prioritised our digital agenda and invested in supervisory technologies (suptech). We now have tools in place that allow fast access to connected data, such as the ownership structures of significant banks, that provide centralised access to all prudential data, and that speed up our fit and proper assessments.[21]

Outreach

But we are not supervising in a vacuum – we need to continuously and transparently connect with all stakeholders.

Accountability to European institutions is essential − to explain the risks we are seeing and how we are addressing them. Legislation provides the legal framework of what we do and it shapes the environment in which banks operate. The implementation of Basel III in the EU is a crucial element of this. In addition, a credible resolution framework is important for supervision. While great progress has been made, remaining gaps need to be closed. I thus fully support the crisis management and deposit insurance (CMDI) package.[22]

More broadly, we need to reach out to the citizens we serve. Many people are concerned about rising borrowing costs and financial strain. They see, at the same time, that banks are highly profitable. This can lead to feelings of injustice. That is why we need to explain our role as prudential supervisors — to ensure that banks remain resilient, that they do not take excessive risks, and that they remain resilient also in times of stress.

And we need to reach out internationally because today’s risks can only be addressed globally. Our largest banks operate in global markets. One-quarter of the exposures of significant institutions are held outside of the EU, and banks are exposed to shifts in global market sentiment.[23] Therefore, we closely cooperate with our international counterparts to prevent fragmentation and regulatory arbitrage. Risks from non-bank financial institutions and the risks from banks outsourcing to big tech firms are two main areas where we need a unified global approach.

Conclusion

Allow me to conclude.

We live in uncertain times. But resignation or even fear is not a good guide to deal with uncertainty. In Europe, we can build on strong institutions and a sound regulatory framework, both to build resilience and to take preventive measures. This is at the core of our work in European banking supervision.

Banks are an integral part of our economies and they can contribute significantly to welfare. They are better capitalised and more resilient than at the start of the banking union ten years ago. But there is no room for complacency.

Structural change in the real economy, newly emerging risks, digitalisation and increased competition can challenge banks’ business models. Recently, banks’ profits have benefited from higher interest rates. This provides the opportunity for banks to increase their resilience, in terms of building capital buffers and resilient IT infrastructures.

On the supervisory and regulatory side, we also need to adapt to a changing environment. Closing gaps in the resolution framework and completing the CMDI review is an integral part of this. And as supervisors, we need to focus on emerging risks and take timely action if we see weaknesses in banks’ risk controls and resilience.