New bank taxes implemented across Europe in the last 18 months could be in place much longer than originally planned, intensifying concerns among investors already wary of the region’s lenders.

|

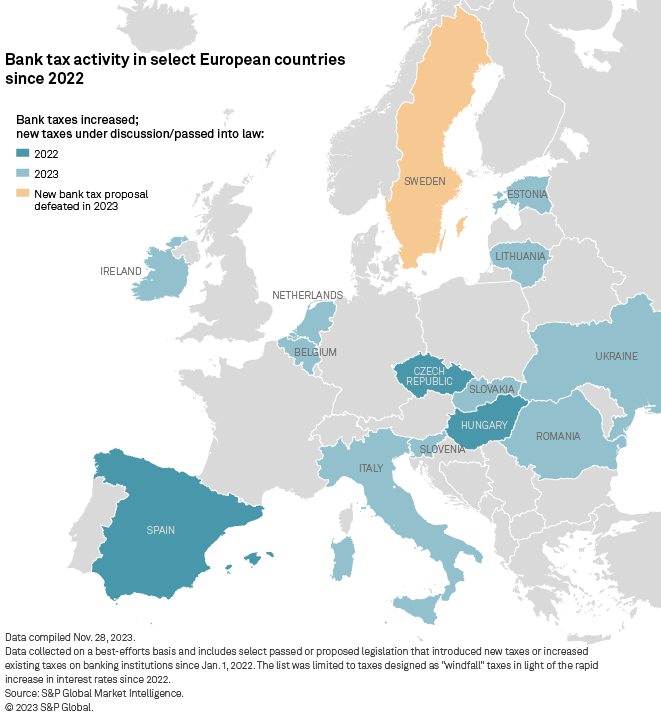

Several European governments have hit lenders with fresh levies as many banks enjoy a surge in revenues and profits from rapidly rising interest rates. Spain and Italy are the two largest European economies to have introduced new bank taxes and several other governments, particularly in central and Eastern Europe, have followed suit.

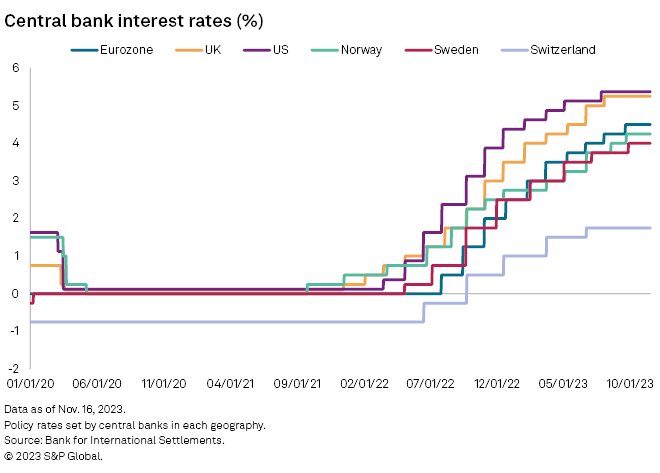

A coalition deal to form a government reached by two of Spain’s left-wing parties in October includes an extension of the country’s bank tax beyond its original two-year time frame, raising the prospect that other governments could do the same. The likelihood that interest rates may remain at or around current levels based on market forecasts is also increasing the potential for the taxes to linger.

“While some of the windfall taxes have specific end dates, I think many will be extended beyond those dates,” Adrian Prettejohn, Europe economist at consultancy Capital Economics told S&P Global Market Intelligence. “The [US economist Milton] Friedman quote ‘nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program’ comes to mind.”

Uncertainty among investors about the permanence of recently introduced taxes and the potential for new levies in other jurisdictions has almost certainly weighed on European bank stocks in the last 18 months, said Johann Scholtz, bank equity analyst at Morningstar.

The median price-to-book value for Europe’s largest banks remained relatively flat between January 2022 and November 2023, S&P Global Market Intelligence data shows, even though higher central bank rates have boosted lending income and bottom-line profits.

“The impact of these taxes on investor sentiment is really where the problem lies,” Scholtz said. “Investors are increasingly seeing European banks almost as quasi-nationalized kind of entities, which obviously doesn’t do a lot to make them more attractive.”

US investors have flagged the increasing introduction of new taxes on European banks as a worry, added Scholtz, who recently visited the country for a series of client meetings. “That was a big concern of US clients, probably the number one concern,” he said.

Higher provisions for taxes

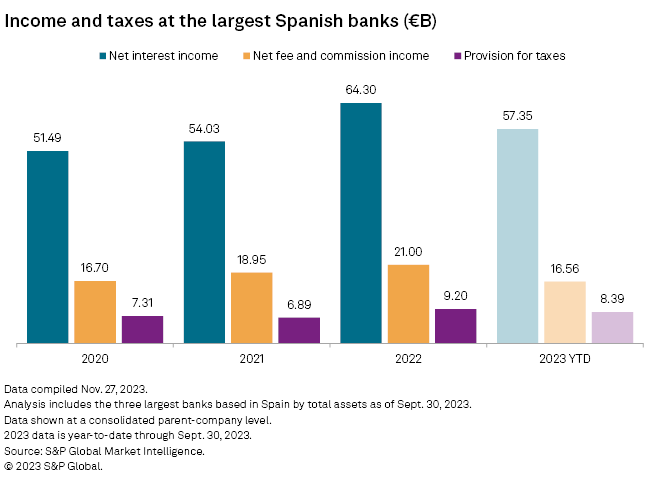

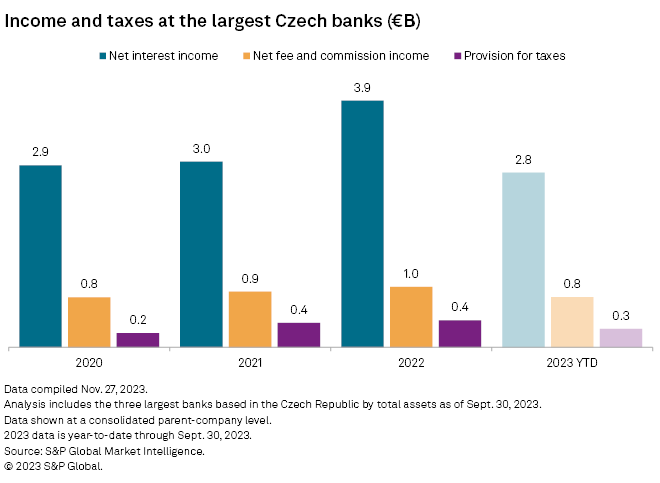

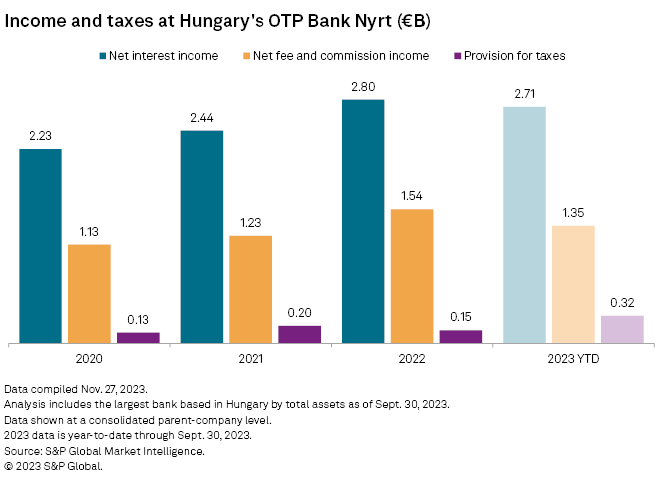

Banks in Spain, Hungary and Czechia — the three European countries that introduced new bank taxes in 2022 — recorded significant increases in aggregate provisions for taxes last year, according to an analysis of S&P Global Market Intelligence data based on a sample of the largest banks in these jurisdictions.

Banks in the three countries are on course to have even higher aggregate provisions for taxes in 2023 based on year-to-date data.

The new taxes come on top of bank levies introduced in many European countries in the years following the global financial crisis. Banks in the 21 European Banking Union countries have also been required to contribute to the Single Resolution Fund, an emergency fund for resolving failing banks, since 2016.

It also comes as many European governments wrestle with rising national debt

Spain’s coalition government likely sees the bank tax as an easy way to finance an increase in spending without expanding the country’s deficit, said Prettejohn. “Other governments will probably take a similar view, especially with pressure from the [European Union] to tighten fiscal policy,” he said.

Rising populism in Europe has also encouraged the adoption of such policies as anti-establishment parties have ascended to power, while many traditionally centrist parties have felt electorally pressured to adopt similarly populist measures.

“From a political perspective, it is always better to tax companies and tax the banking industry than tax citizens,” said Francisco Uria, global head of banking and capital markets at KPMG.

Backlash

Still, the threat of a backlash from investors could discourage more European governments from considering such measures. Shares in Italy’s two largest banks, Intesa Sanpaolo SpA and UniCredit SpA, plunged by more than 7% in August when the Italian government announced its plans for a tax,

“I would venture to say that it’s probably become harder for the countries that haven’t implemented new taxes yet to implement them given the kind of reaction we’ve seen from the market,” said Scholtz.

Countries whose banks have not experienced significant increases in NII, such as France, are also unlikely to consider new taxes on the sector, Scholtz added.

The recent freeze in interest rates and ongoing increase in deposit costs mean governments may also find it harder to warrant introducing such measures. “We increasingly think that net interest margin expansion has kind of peaked, so the justification for these kinds of special taxes becomes less evident,” Scholtz said.

For now, European governments still have “valid economic arguments” for targeting banks for additional tax revenue, said Prettejohn. The taxes are targeting excess profits that have accrued partly due to “market inefficiencies” arising from the lack of competition for deposits that has kept banks’ deposit costs low, he said.

“Furthermore, banks are getting paid a much higher rate on their reserves at the ECB than they are paying on the corresponding customer deposits, so effectively they’re getting a subsidy from the [European Central Bank] without taking on any risk,” Prettejohn added. “The windfall taxes can be seen as just reducing some of this subsidy.”

The ECB itself moved in July to reduce that “subsidy” when it announced it would no longer remunerate bank’s mandatory minimum reserves beginning Sept. 20. Minimum reserves are reserve balances that credit institutions are required to hold with the central bank equivalent to 1% of specific liabilities, mainly customers’ deposits.

The recent wave of European countries adopting new bank taxes could smooth the way for more governments to do so, said Pablo Ulecia, EMEIA banking and capital markets tax and law leader at EY. “It’s easier for governments to introduce these kinds of taxes on banks once you have peers doing something similar, especially if you are aligned politically [with those peers],” Ulecia said.

Higher for how much longer?

The experiences of governments that have introduced bank taxes could provide a useful guide for those governments considering such measures, giving them more confidence to undertake the process, according to Prettejohn. The further spread of bank taxes in Europe is also likely to make regulators gradually more accepting of the trend, reducing the potential pushback for governments if they adopt the policy, he added.

For those governments that decide to keep the recently implemented taxes in place, the direction of interest rates will be key to determining the longevity of the measures. The ECB’s deposit facility rate is expected to fall to 2.5% by the end of 2025 from 4.0% currently and then rise to 3.0% by 2030, according to Capital Economics forecasts.

“If interest rates fall significantly then banks’ profits will likely decrease, making it harder for governments to argue for windfall taxes [remaining in place],” said Prettejohn. “With that in mind, you might expect the windfall taxes to be wound down around the time that any loosening cycle is complete.”