Overhaul of Regulatory Capital Requirements Proposed by US Banking Regulators | Perspectives & Events

On July 27, 2023, US federal banking regulators issued proposals to (i) significantly revise the risk-based regulatory capital requirements for certain midsize and larger US banking organizations (the “Capital Proposal”) and (ii) change the method for calculating the capital surcharge for globally systemically important banking organizations (“G-SIBs”) (the “G-SIB Surcharge Proposal”).1 These proposals are of critical importance because the amount of capital a bank must maintain with respect to any particular loan, investment or activity is typically a significant – if not the most significant – factor in determining whether the relationship is profitable or even feasible.2 Comments on both proposals are due by November 30, 2023.

The Capital Proposal would apply to any banking organization with $100 billion or more in assets, as well as others with significant trading activity, and would significantly increase the capital requirements for most institutions.3 This would cover the 8 US G-SIBs, approximately 22 larger and midsized US bank holding companies (ranging from traditional regional banking organizations to credit card and other niche organizations), 10-12 US intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations, and 7-10 other US banking organizations. It would not directly affect credit unions, US branches and agencies of foreign banking organizations, or the non-US operations of foreign banking organizations.

The Capital Proposal would make material changes to the calculation of risk-based capital requirements and expand the range of risks for which capital must be held. Although the Capital Proposal is intended to implement 2017 changes to international capital standards (the “Endgame Standard”) adopted by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (“Basel Committee”), US regulators have made significant changes that expand the range of institutions covered by the Capital Proposal and impose more stringent requirements than those adopted by the Basel Committee. Further, while US regulators initially signaled that capital levels would not be materially impacted by the Endgame Standard, the Capital Proposal is now expected to increase common equity Tier 1 (“CET1”) capital by around 16% for banking organizations subject to the Capital Proposal.4

As discussed below in more detail, most importantly, the Capital Proposal would:

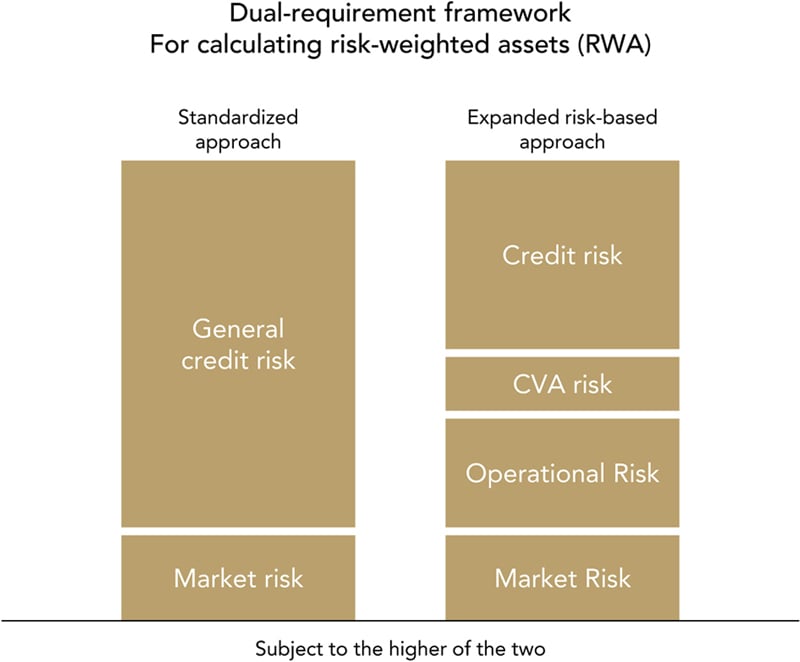

- Replace the advanced approaches for credit risk with an “expanded” standardized approach that is a more stringent version of the Endgame Standard.

- Require these banking organizations to calculate their risk-based capital ratios under the existing standardized approach and expanded standardized approach (a “dual-stack” requirement) and use the lower (less favorable) ratio of the two.

- Result in an overall increase in the market risk capital requirements and impose stricter requirements for using models in order to calculate market risk.

- Replace the model-based approach for operational risk with a standardized framework for operational risk capital.

- Eliminate the opt-out for accumulated other comprehensive income (“AOCI”).

- Apply these revised capital requirements to all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets.

- Impose an output floor that would limit the amount that capital calculated with internal models could deviate from the expanded standardized approach to 72.5%.

The release of the Capital Proposal was marked by significant dissents by principals of the FDIC and Federal Reserve. At the FDIC, Vice Chair Travis Hill and board member Jonathan McKernan voted against issuing the Capital Proposal and issued strong statements sharply critical of it, particularly the deviation from the Endgame Standard. Similarly, Federal Reserve Governors Michelle Bowman and Christopher Waller voted against issuing the Capital Proposal and raised concerns about its potential economic impacts. Although Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell and Governor Philip Jefferson voted to issue the Capital Proposal, each made statements indicating concerns about its potential effect and signaled that they would be looking to make changes to it. Of potential significance, the day after the Capital Proposal was issued, the US Senate initiated the process for confirming Dr. Adriana Kugler to be a governor on the Federal Reserve Board. If confirmed, Dr. Kugler could provide an important vote for finalizing the Capital Proposal.

A rare lack of consensus among the principals of the FDIC and the Federal Reserve regarding the Capital Proposal raises the prospect that material changes could be made before it is finalized. The prospect of changes could be further increased as Congress has already requested that US banking regulators testify about the Capital Proposal due to concerns about the adverse potential impacts of it on the economy, financial markets, and lending.5 Due to the lack of consensus among banking regulators, the substantial public interest in the Capital Proposal and the 120-day comment period plus the time the regulators will need to consider the numerous filed comments, it is likely the Capital Proposal will not be finalized until well into 2024 at the earliest.

If adopted in its current form, the Capital Proposal could have a considerable impact on the operations of banking organizations subject to it and on the overall US banking industry. To start, the Capital Proposal would require banking organizations to substantially increase their capital levels from a combination of retained earnings, new equity issuances, a reduction in assets, or a combination of these. In addition, midsize banking organizations that have not been subject to sophisticated capital requirements would need to adopt more advanced capital operations and strategies. This would go beyond mere calculation of capital and also include creating new off-balance sheet and synthetic securitization structures, issuing new types of capital instruments, and identifying alternative funding sources.6

The Capital Proposal’s increases in capital requirements would also increase the costs of bank lending and trading activities, driving some of these activities to nonbank financial institutions, or increase the costs for customers and counterparties in the Main Street economy. These costs could be particularly impactful for midsized banking organizations that had not previously been subject to advanced capital requirements. Accordingly, the increase in capital requirements and the costs associated with them could intensify already-existing pressure on smaller affected banking organizations to become larger, including through mergers, in order to spread the costs over a large asset base. Given the Biden Administration’s focus on antitrust, it is curious that the Capital Proposal does not discuss its potential impact on market concentration.7 From an international perspective, the Capital Proposal could reduce the competitiveness of US banking organizations versus banking organizations from jurisdictions with less punitive capital standards, including the Endgame Standard, potentially limiting international engagement by US banking organizations and further reducing foreign bank participation in the US market.

The Capital Proposal would also materially impact banking organizations with significant fee income operations as it includes new operational risk capital charges that are based, in part, on the amount of fee- or commission-based income, including fiduciary and custody services, loan servicing, securities brokerage, investment banking, advisory and underwriting, and insurance. The Capital Proposal also would disproportionately impact banking organizations that are credit card issuers or have significant amounts of low-risk assets, including noncontrolling investments in US nonbanking companies, which are common among foreign banking organizations.

The G-SIB Proposal would significantly impact banking organizations with substantial cross-border activity, particularly foreign banking organizations that control larger US banking organizations. Although the stated intent of the G-SIB Proposal is to improve the “precision of the G-SIB surcharge,” the changes to the calculation of the cross-jurisdictional activity indicator to include derivatives exposures would cause 9 banking organizations or their intermediate holding companies to shift into Category II from Categories III and IV for purposes of the enhanced prudential standards. In addition, because US regulators made significant deviations in the Capital Proposal from the Endgame Standard, the Capital Proposal would effectively impose higher costs on banking organizations based, or operating, in the United States.

However, there could be some winners under the Capital Proposal, although not necessarily those who the banking regulators intended. The Bank Policy Institute noted in response to the Capital Proposal that “private equity, private debt, hedge funds, finance companies and other unregulated firms” would likely gain market share with higher margins.8 These entities also may find opportunities to help banking organizations directly by facilitating transactions that reduce risk (e.g., credit risk transfer trades), acquiring credit exposure through off-balance sheet securitizations and commercial paper conduits, and purchasing assets or activities that incur high capital charges but do not need to be held by, or undertaken in, a banking organization (e.g., certain payment card activity, investment banking, and derivatives dealings). Within the US banking system, there are likely to be competitive shifts as banking institutions that do not engage in activities most impacted by the Capital Proposal (e.g., trading activities, fee- or commission-based activities) benefit on a relative basis as the Capital Proposal would have more impact on their competitors.

In this Legal Update, we provide background on the regulatory capital requirements, discuss the Capital Proposal and G-SIB Surcharge Proposal, and highlight a number of the likely potential impacts.

Background

Since the 1980s, US banking organizations have been required to comply with regulatory capital requirements.9 Under current regulatory capital requirements, US banking organizations must satisfy certain minimum capital to risk-weighted asset (“RWA”) ratios (the “risk-based capital ratios”) and capital to total assets ratios (the “leverage ratios”).10 They also may be required to maintain one or more additional capital buffers, known as the capital conservation buffer, countercyclical capital buffer and G-SIB surcharge. These requirements were established or significantly increased after the 2008 financial crisis, and, today, banking organizations of all sizes are expected to maintain robust capital ratios.11

Several years following the financial crisis and subsequent implementation of the Basel III rules, banking regulators modified a number of requirements in order to tailor these based on the size of, and the complexity and riskiness of the activities of, financial institutions. As discussed below, in many respects, the Capital Proposal would apply new or heightened requirements to banking organizations across categories, which would have the effect of substantially undoing this regulatory tailoring by imposing more uniform capital requirements.

Banking organizations are required to comply with other capital-related requirements, including capital adequacy assessments, capital stress testing, and capital planning.12 Banking organizations whose deposits are insured by the FDIC also may be subject to supervisory action under the prompt corrective action framework if they are not adequately capitalized.

Many US regulatory capital requirements are broadly derived from regulatory capital standards maintained by the Basel Committee. In 2017, the Basel Committee finalized revisions to its regulatory capital standards in a consultation process that the industry refers to as “Basel IV” or the “Basel Endgame.” The goal of Basel Endgame was to reduce excessive variability of capital requirements across institutions while not significantly increasing capital requirements.13 The revisions were extensive and the Basel Committee intended for national governments to implement most of the Basel Endgame revisions by January 1, 2022, although this deadline was extended until January 1, 2023, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, the federal banking regulators informally signaled for several years that they were considering how to address the Basel Endgame revisions but did not release a proposal until last week.14

The Proposals

The Capital Proposal is over 1,000 pages and addresses nearly every section of the existing regulatory capital requirements. While the Capital Proposal does not directly increase the capital requirements, it generally would result in an overall increase in the amount of capital a banking organization must hold by changing the ways in which certain risks, asset amounts, and exposures are calculated. Additionally, it will apply new capital requirements to certain banking organizations, which clearly will result in an increase in the overall capital requirements for those organizations.

Scope

As noted above, regulatory capital requirements vary depending on the size and activities of a banking organization. At one end are the largest US banking organizations, which are subject to the most extensive capital requirements, including the G-SIB surcharge. At the other end are qualifying community banking organizations that have elected to use the community bank leverage ratio framework, which are subject to simplified requirements consisting of a 9% leverage ratio.

The Capital Proposal would revise the regulatory capital requirements for US banking organizations with significant trading activity or total consolidated assets of $100 billion or more. Under the Capital Proposal:

- All US banking organizations with total consolidated assets of $100 billion or more would be:

- Subject to an expanded standardized approach for credit risk, a non-modeled approach for operational risk, an approach for credit valuation adjustment (“CVA”) risk and a more restrictive hybrid approach for market risk.

- Required to comply with the supplementary leverage ratio and countercyclical capital buffer requirements, include all components of accumulated other comprehensive income (“AOCI”) in the calculation of capital and make certain other deductions and special treatments under the capital rules.

- All other US banking organizations with aggregate trading assets and trading liabilities equal to 10% or more of total assets or $5 billion or more would be required to comply with the more restrictive hybrid approach for market risk.

Banking organizations with less than $100 billion in total consolidated assets would remain subject to the existing standardized approach and leverage ratio requirement, the community bank leverage ratio framework or the small holding company policy statement.

The Capital Proposal and G-SIB Surcharge Proposal generally collapse Categories II, III and IV into a single bucket.15 In doing so, they would effectively undo many of the capital-related aspects of the Federal Reserve’s 2019 tailoring initiative for larger regional banking organizations, which implemented the Regulatory Reform, Economic Growth and Consumer Protection Act of 2017. In a recent speech, Vice Chair Michael Barr stated that this action is an appropriate response to the recent failures of certain US regional banking organizations, which demonstrated that even banks of this size can cause stress that spreads to other institutions and threatens financial stability. However, it remains unclear how capital requirements would have addressed the recent failures, which were largely precipitated by liquidity risk and deposit runs, not capital shortfalls. Of note, Chair Powell observed in his comments on the Capital Proposal that, although regulatory requirements needed to be tightened in response to the recent bank failures, to preserve a banking system with banks of different sizes, “[r]egulation and supervision should reflect the size and risks of individual institutions.”16

Regulatory Capital

Currently, banking organizations calculate the amount of regulatory capital they hold by aggregating the adjusted accounting values of eligible capital instruments such as common stock, retained earnings, and certain preferred shares.

The Capital Proposal generally would not change the eligibility criteria for regulatory capital instruments or the regulatory adjustments and deductions to these instruments. However, it would require all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets to account for unrealized losses and gains in their available-for-sale securities when calculating regulatory capital. It also would require Category III and IV banking organizations to disclose that the holders of new Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital instruments may be fully subordinated to interests held by the US government if the banking organization enters into a receivership, insolvency, liquidation, or similar proceeding.

The first change effectively would undo the longstanding option for banking organizations that are not subject to the advanced approaches discussed below (i.e., Category III and IV organizations) to opt out of the requirement to include in CET1 capital all components of AOCI (with the exception of accumulated net gains and losses on cash flow hedges related to items that are not fair-valued on the balance sheet).17 For some banking organizations, AOCI may constitute as much as 70% of CET1 capital, with the average across affected banking organizations being in excess of 18% of CET1 capital. Additionally, all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets would be required to apply the capital and total loss absorbing capacity holdings deductions and minority interest treatments18 that are currently applicable to Category I and II banking organizations.

Credit Risk Capital Requirements—Expanded Standardized Approach

Credit risk is the possibility that an obligor, including a borrower or counterparty, will fail to perform on an obligation. Currently, all banking organizations (other than certain community banking organizations) calculate the amount of assets against which they must hold capital for credit risk under the standardized approach. The standardized approach requires banking organizations to multiply the amount or exposure of each on-balance sheet asset by a specified risk weight (percentage) to determine the risk-weighted amount of the asset. Risk weights are assigned in the capital rule and reflect a regulatory assessment of the comparative levels of risk of different types of assets and exposures (as well as certain policy judgments by regulators and legislators). Off-balance sheet exposures are included through the use of credit conversion factors, which apply a percentage to the notional amount of the exposure prior to applying the risk weight (as if the exposure were on-balance sheet). There are additional provisions that address derivatives transactions, centrally cleared transactions, guarantees and credit derivatives, collateralized transactions, unsettled transactions, securitization exposures, and equity exposures.

The Capital Proposal would create a new, expanded standardized approach for credit risk (the “expanded standardized approach”) based on the existing standardized approach. The Capital Proposal would require that banking organizations with total consolidated assets of $100 billion or more determine their RWAs under the expanded standardized approach (and adjust their RWAs for operational, credit valuation adjustment, and market risks, as discussed below). However, they would need to continue calculating risk-based capital ratios assets under the existing standardized approach and use the lower ratio (i.e., higher amount of RWAs) of the two when determining compliance with the regulatory capital requirements (see graphic below).

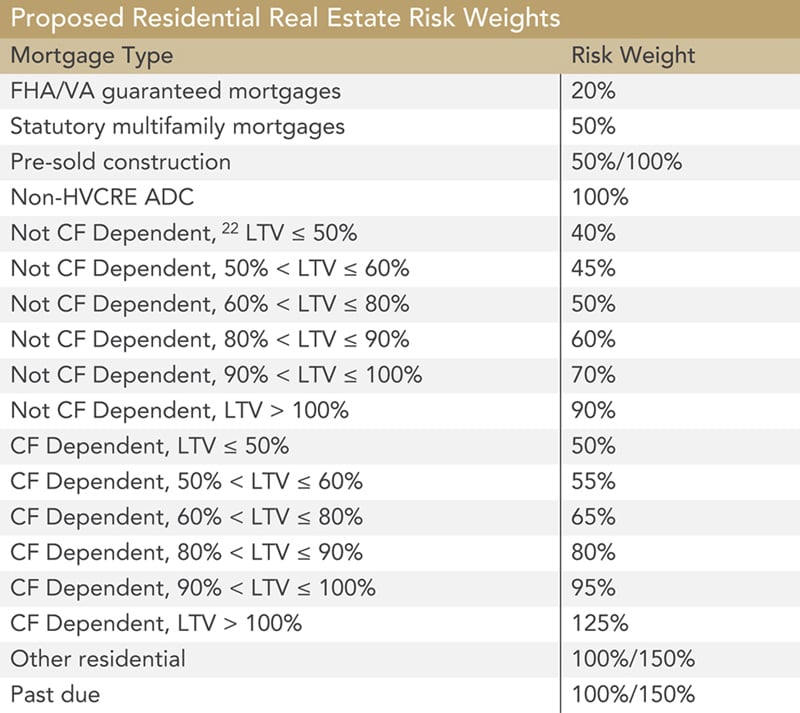

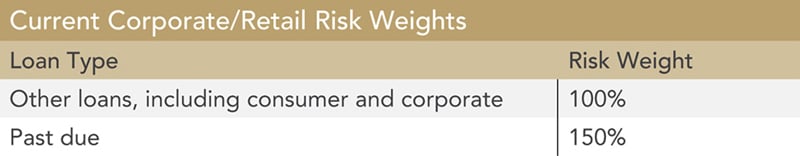

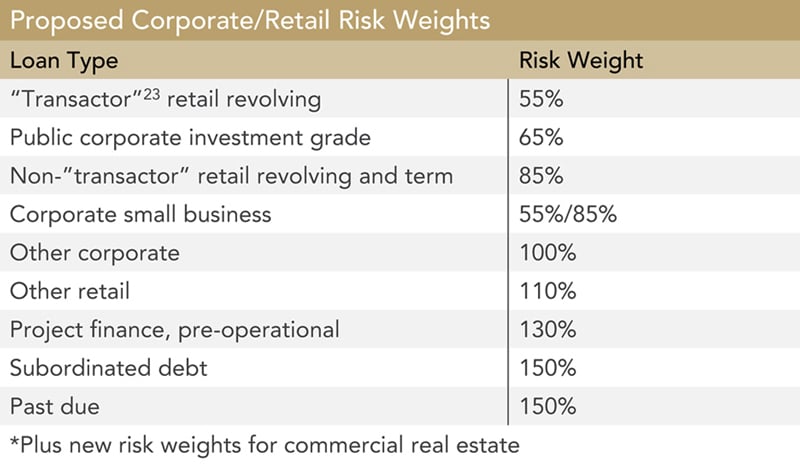

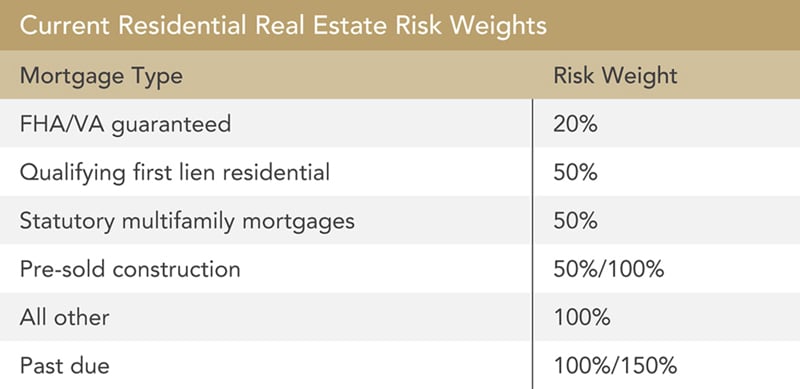

The expanded standardized approach would include new risk weightings derived from the Endgame Standard.19 For example, currently exposures to real estate are subject to a handful of risk weights, the application of which is driven by the presence of guarantees or statutory exceptions. In an attempt to make the capital requirements more sensitive to the varying risks of different types of credit exposures, the Capital Proposal would create many new risk weights for residential and commercial real estate and their application would be driven by dynamic20 loan-to-value (“LTV”) ratios, reliance on cash flow from the property, and the creditworthiness of the underlying borrower (see comparative chart below).21 These are similar to the more granular risk weights in the Endgame Standard but with a 20% increase to each risk weight.

Additionally, there would be new sets of risk weights established for retail; subordinated debt instruments; specialized lending; commercial real estate (“CRE”); and acquisition, development or construction exposures.

Further, the Capital Proposal generally would impose a punitive treatment under the expanded standardized approach for undrawn commitments by raising the credit conversion factor for unconditionally cancelable commitments from 0% to 10% and establishing a single 40% credit conversion factor for all commitments that are not unconditionally cancelable. These changes in particular may have a significant impact on consumer credit cards and certain committed facilities supporting asset-backed commercial paper programs, which historically have qualified for a 0% risk weight by having credit limits that are unconditionally cancelable. The Capital Proposal also would impose capital requirements on undrawn commitments that have no express contractual maximum amount or pre-set limit.

The Capital Proposal addresses securitizations by adopting a form of the securitization framework that is used in the advanced approaches, with modifications that include: (i) additional operational requirements for synthetic securitizations (which would include credit risk transfer trades and certain credit derivatives and structural securitizations); (ii) a new securitization standardized approach, as a replacement to the supervisory formula approach and standardized supervisory formula approach; (iii) new maximum capital requirements and eligibility criteria for certain senior securitization exposures (i.e., the long-sought “look-through approach”); and (iv) a new framework for non-performing loan securitizations. It also would lower the risk weight floor for certain securitization exposures from 20% to 15%.

The Capital Proposal also would make changes to the risk weights for exposures to other financial institutions and equity exposures.

Credit Risk Capital Requirements—Advanced Approaches

The Capital Proposal would eliminate the advanced approaches for credit risk, prohibiting the use of internal models, the value-at-risk (“VaR”) approach and similar models to calculate credit risk.24

Credit Risk Capital Requirements—Leverage Ratio Framework

The Capital Proposal would retain the current leverage ratio, supplementary leverage ratio, and enhanced supplementary leverage ratio requirements25 and does not appear to even consider certain Basel Committee revisions related to them.26 It would extend the supplementary leverage ratio requirement to apply to all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets and require these organizations to use the standardized approach to counterparty credit risk (“SA-CCR”) to calculate derivatives exposures.27 Using the SA-CCR for those banking organizations that currently do not do so generally will result in higher derivatives exposures being included in the calculation of total leverage exposure. As a result, this change might result in a re-evaluation by these banking organizations of the desirability of offering or using these products.

The Capital Proposal does not address concerns that the leverage ratio requirements impose punitive disincentives to holding central bank reserves and government securities. This inaction may be because the increased capital requirements imposed by the Capital Proposal would effectively remove the leverage ratio requirements as binding constraints on many banking organizations.28 However, by resolving the problem arising from the leverage ratio being a binding restraint on banking organizations, the Capital Proposal may worsen a different problem by requiring organizations to hold even higher capital against these low-risk assets.

Market Risk Capital Requirements

Currently, certain banking organizations calculate an amount of assets against which they must hold capital for the market risk of their trading activities (as an adjustment to risk-based capital). The market risk capital requirement applies to covered positions, which are trading assets and liabilities that satisfy certain requirements (commonly known as “trading book” positions).29

A banking organization currently is subject to the market risk capital requirement if its aggregate trading assets and trading liabilities equal 10% or more of total assets or $1 billion or more. About 40 banking organizations currently are subject to the market risk capital requirement. The Capital Proposal would change the threshold for applying the market risk capital requirements by increasing the absolute threshold trigger from $1 billion to $5 billion in aggregate trading assets and trading liabilities. Further, banking organizations would be permitted to exclude customer and proprietary broker-dealer reserve bank accounts from the calculation of trading assets and liabilities. However, all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets would be subject to the market risk capital requirements (to the extent they engage in any trading activity).

Market risk consists of general and specific market risk. General market risk is the risk of loss that could result from broad market movements, such as changes in the general level of interest rates, credit spreads, equity prices, foreign exchange rates, and commodity prices. Specific risk is the risk of loss on a position that could result from factors other than broad market movements and includes event and default risk as well as idiosyncratic risk.

A banking organization currently calculates a measure for market risk, which equals the sum of the VaR-based capital requirement, stressed VaR-based capital requirement, specific risk add-ons, incremental risk capital requirement, comprehensive risk capital requirement, and capital requirement for de minimis exposures. This market risk measure is used to adjust an organization’s total RWAs.

The Capital Proposal would generally increase the market risk capital requirements through several changes to existing rules. Regulators indicated in the Capital Proposal that this increase would be more than 40%, not including operational costs such as those related to re-evaluating the boundary of the trading book and re-scoping the market risk capital test in the Volcker Rule.

The Capital Proposal generally appears to retain the intent test30 for assigning instruments and exposures to the trading book, but assignment determinations would be subject to mandatory rules that are more comprehensive than the current framework and documented at inception and thereafter annually.

Switching exposures between the trading book and banking book would be strictly limited and irrevocable. A banking organization would be able to move an exposure between books without penalty only in extraordinary circumstances, such as permanent closure of a trading desk or a change in accounting standards, and subject to regulator approval. Under no circumstance would a banking organization be permitted to recognize a capital benefit as a result of switching. Note that it is unclear how the Capital Proposal would apply to positions that currently sit on the “wrong” book (i.e., whether the assignment rules or the prohibition against switching would prevail).

The Capital Proposal would require banking organizations to use a models-based approach or a standardized measure for determining the risk weights for positions in the trading book. Some risk weights would continue to be assigned through the use of models, and, in a change from existing requirements, modeling of risk would occur at the level of individual trading desks for particular asset classes, instead of at the organization level.31 Additionally, banking organizations would be allowed to develop and use their own models for certain types of market risk, subject to extensive governance controls and technical specifications. However, the Capital Proposal would require the use of the standardized measure for risks that regulators deem are “too hard” to model or otherwise are ineligible (e.g., lack of trading desk approval).

For some banking organizations, the measure of market risk already is a significant contributor to the calculation of RWAs and can constitute as much as 20% of total RWAs. The increases in the Capital Proposal are likely to make market risk capital requirements a significant issue for an even larger number of banking organizations. This may lead to a reduction in certain trading activities.

There also are banking organizations that currently are not subject to the market risk capital requirements but might become subject to these as a result of the redefined boundary between the trading book and banking book. Currently these banking organizations apply the market risk capital requirements in an indirect manner when they report trading assets and liabilities on the applicable reporting form (e.g., FR Y-9C). Under the Capital Proposal, these banking organizations could become subject to the market risk capital requirement if the new definitions for trading assets and liabilities push them above the 10% or $5 billion thresholds.

Even more notably, the Capital Proposal also does not appear to address the interaction between the market risk capital requirements and the global market shock component of the Federal Reserve’s stress capital buffer (“SCB”) requirement, although it does include the revised approach to market risk capital in the determination of the SCB requirement. The market risk capital requirements are designed to hold capital against tail risks in the change of value of a position, while the global shock component is designed to ensure that a banking organization has enough capital to withstand a sudden change in the value of its positions. Commentators have noted that both requirements capture the risk of market risk losses from trading operations, and, therefore, regulators should coordinate the requirements to avoid double-counting risk.32 This is because the market risk capital requirements are designed to hold capital against tail risks in the change of value of a position, while the global market shock component is designed to ensure that a banking organization has enough capital to withstand a sudden change in the value of its positions. Unfortunately, while the Capital Proposal does include a revised approach to market risk capital in the determination of the SCB requirement, the Capital Proposal does not appear to have addressed the double-counting concern raised by the interaction of the market risk capital requirements and the global shock component.

Operational Risk Capital Requirements

Currently, only banking organizations that use the advanced approaches are required to calculate an amount of assets against which they must hold capital for the operational risk of their activities.33 Operational risk means the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems or from external events (including legal risk but excluding strategic and reputational risk).

A banking organization currently uses internal estimates of its operational risks to generate an operational risk capital requirement, which is used to adjust an organization’s total RWAs. A banking organization’s estimate of operational risk exposure includes both expected operational loss (“EOL”) and unexpected operational loss, unless the organization can demonstrate that it has eligible operational risk offsets that equal or exceed its EOL.

The Capital Proposal would replace the internal estimate of operational risk with a standardized measure (formula). This change would result in a banking organization approximating its operational risk capital charge based on the organization’s activities and then adjusting the charge upward based on the organization’s historical operational losses. The new operational risk capital requirements would apply to all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total consolidated assets.

The application of the standardized measure for operational risk would be calculated based on a banking organization’s aggregate operational risks (the business indicator marginal coefficient), potential shocks to interest income, the income and expenses from advice and services (i.e., fee income/expenses), exposure to net financial operating losses, and a measure of its comparative operational risk exposure (the internal loss multiplier). Banking organizations with higher overall business volume will likely have higher operational risk capital charges. Each component is based on further sets of assumptions, and, in the following paragraphs, we focus on the components which have raised significant concerns early in the comment period.

The banking organizations likely to be impacted by this new operational risk capital charge are those with higher overall business volume and fee/commission-based businesses. Fee and commission income includes fiduciary activities, service charges on deposit accounts in domestic offices; fees and commissions from securities brokerage; investment banking, advisory, and underwriting fees and commissions; fees and commissions from annuity sales; income and fees from mortgage servicing assets and securitization activities; income and fees from issuing letters of credit; safe deposit box rent; debit card and credit card interchange fees; income and fees from wire transfers; underwriting income from insurance and reinsurance activities; and income from other insurance activities.34 Under the Capital Proposal, the maximum value of the component for interest income is capped at 2.25% of interest-earning assets, but the component for services-related income/expenses is not capped. Importantly, services are treated uniformly, meaning that revenue from routine, low-risk activities (e.g., safe deposit box rental) would count the same as revenue from more esoteric or high-risk activities (e.g., investment banking fees, commissions on securities brokerage). This further means that banking organizations with significant fee-based income (or expenses) may see very large operational risk capital charges, exceeding 20% of current RWAs in some circumstances.35

With respect to the component for a bank’s comparative operational risk exposure, or internal loss multiplier, the Capital Proposal would set it based on 15 times the average annual operational risk losses incurred by the organization over the previous 10 years. This approach will require banking organizations to develop systems and procedures to capture and value net material operational loss events on an enterprise-wide basis. The Basel Committee contemplated a 5-year transition period for banking organizations to accumulate data (and assuming that banking organizations already have 5 years of high-quality data), which the Capital Proposal includes, as well as a default multiplier of 1 when less than 5 years of data has been collected. However, by generally setting the internal loss multiplier based on a banking organization’s unique operational loss experience (and with a floor of 1), the Capital Proposal introduces the potential for greater variability in operational risk capital charges (e.g., from organizations using different techniques to capture and quantify loss events) and overstated capital requirements.

The Capital Proposal retains the Basel Committee’s definition of “operational risk.” That definition has not been revised for many years, and some financial services professionals have expressed concern that it does not reflect more recent developments in operational risk, such as the rise of cyber risk.36 Therefore, banking organizations will need to consider if the Capital Proposal requires them to use an antiquated, simplistic definition instead of more modern frameworks that they may use for internal risk management purposes (e.g., Operational Risk data eXchange taxonomies).

The Capital Proposal also indicates that operational risk capital charges (as well as credit valuation adjustment risk capital requirements, discussed below) would be considered as part of the determination of the SCB, which is likely to lead to comments regarding duplication of risk. Currently, operational risk capital charges are not imported into the determination of a banking organization’s SCB, which relies on only the standardized approach because doing so would be double-counting of operational risks through the calculation of RWAs and the stress testing of pre-provision net revenues. Accordingly, the Capital Proposal would cause the SCB to substantially overcharge for operational risk.

Credit Valuation Adjustment Risk Capital Requirements

Credit valuation adjustment (“CVA”) risk is the possibility of losses arising from changing instrument values in response to changes in counterparty credit spreads and market risk factors that drive prices of derivatives transactions and securities financing transactions.37 Currently, the capital charge associated with CVA risk is incorporated in the standardized approach and advanced approaches to credit risk.

The Capital Proposal would extract the CVA risk capital requirement from the credit risk provisions and require all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets to maintain an amount of capital for CVA-risk covered positions. The Capital Proposal would define a CVA-risk covered position as a derivative contract that is not a cleared transaction. In addition, the Capital Proposal would allow a banking organization to choose to exclude an eligible credit derivative for which the banking organization recognizes credit risk mitigation benefits from the calculation of CVA risk.

CVA risk capital requirements would be calculated using one of two standardized methods. The Capital Proposal also would require banking organizations to implement identification, documentation, and other operational controls to support compliance with the CVA risk capital requirements. These increased costs may lead to further consolidation in derivatives dealing and a reduction in the number of dealers offering certain products.

Long-Term Debt Requirement

Currently, only US G-SIBs and US intermediate holding companies that are controlled by a global systemically important foreign banking organization are required to maintain an amount of outstanding eligible external long-term debt (“Eligible LTD”). For US G-SIBs, the Eligible LTD requirement is the greater of a percentage of the organization’s RWAs and total leverage exposure. In recent months, US regulators had suggested applying an Eligible LTD requirement to banking organizations with more than $500 billion in total assets.38

The Capital Proposal does not contain an Eligible LTD requirement. Therefore, we expect that US regulators will release a further proposal in the next few months that addresses this topic.

G-SIB Surcharge Proposal

The G-SIB Surcharge Proposal generally would not change the G-SIB surcharge framework (e.g., no adjustment to the way in which the G-SIB surcharge applies to holdings of central bank reserves and government securities). It also would not incorporate the Basel Committee framework for crypto asset exposures or the Basel Committee guidance on applying capital requirements to climate-related financial risks.39

However, it would make certain technical changes to the G-SIB surcharge. Most significantly, the G-SIB Surcharge Proposal would make changes to the measurement of some systemic indicators, including revising the systemic indicators for cross-jurisdictional claims and cross-jurisdictional liabilities to include derivative exposures. These changes would result in 7 foreign banking organizations and 2 US intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations moving to Category II from Categories III or IV.

The G-SIB Surcharge Proposal also would reduce “cliff effects” in the G-SIB surcharge by measuring G-SIB surcharges in 10-basis point increments instead of the current 50-basis point increments. It also would measure on an average basis over the full year the indicators that currently are measured only as of year-end. This change is intended to reduce incentives for an organization to reduce its G-SIB surcharge by temporarily altering its balance sheet at quarter or year end.

Other Changes

The countercyclical capital buffer is an add-on to the risk-based capital requirements that generally applies to Category I, II and III banking organizations. The countercyclical capital buffer effectively requires these banking organizations to maintain a buffer of additional CET1 capital that is in excess of the capital the organization is required to hold in order to satisfy its minimum risk-based capital ratios and the capital conservation buffer. Currently, it is set to 0% in the United States and would be increased when the economy is performing well and growing rapidly. The Capital Proposal would apply the countercyclical capital buffer to Category IV banking organizations, thereby making it applicable to all banking organizations with $100 billion or more in total assets.

In addition, the Capital Proposal would also introduce enhanced disclosure requirements and align regulatory reporting requirements with the changes to capital requirements. Regulators anticipate that revisions to the reporting forms will be proposed in the near future, which would align with the proposed revisions to the regulatory capital requirements. The revisions introduced by the Capital Proposal would interact with several other Federal Reserve rules, including by modifying the RWAs used to calculate total loss-absorbing capacity requirements, Eligible LTD requirements, and the short-term wholesale funding score included in the G-SIB surcharge method 2 score. Also, the Capital Proposal would revise the calculation of single-counterparty credit limits by removing the option of using a banking organization’s internal models to calculate derivatives exposure amounts and requiring the use of SA-CCR for this purpose.

The preamble to the Capital Proposal requests comment on whether the capital rules should explicitly require banking organizations to perform due diligence to determine whether the minimum regulatory capital requirements for certain exposures sufficiently account for their potential credit risk. If added to the Capital Proposal, this item could greatly increase the underwriting and risk review burden for banking organizations.

Output Floor

An output floor is a restriction on the capital benefits that a banking organization may recognize from the use of internal models to calculate capital requirements. The Capital Proposal would limit the extent to which a banking organization could use internal models for market risk to reduce its capital requirements by imposing an output floor of 72.5%. This output floor would correspond to 72.5% of the sum of a banking organization’s RWAs under the expanded standardized approach, operational RWAs, and CVA RWAs, plus RWAs calculated using the standardized measure for market risk, minus any amount of the banking organization’s adjusted allowance for credit losses that is not included in Tier 2 capital and any amount of allocated transfer risk reserves.

Transition Period

The 2013 Basel III revisions to the US regulatory capital requirements included several transition periods that ranged from 2 to 8 years. In particular, Category I and II banking organizations were given 4 years to phase in the inclusion of AOCI in CET1 capital. Further, some instruments and exposures were permanently grandfathered from having to satisfy the requirements in the 2013 revisions.

The Capital Proposal would become effective on July 1, 2025, and compliance with some changes, such as the expanded scope of the supplementary leverage ratio, may require immediate compliance. Category III and IV banking organizations would be given a 3-year phase-in period to comply with the elimination of the AOCI opt-out, ending on June 30, 2028. In the first year, they would be permitted to recognize 75% of the AOCI adjustment amount (i.e., avoid including 75% of AOCI in CET1 capital), stepping down to 50% in year 2, 25% in year 3, and 0% thereafter. All banking organizations would be given 3 years to phase-in compliance with the changes to the credit, market, operational, and CVA capital requirements. In the first year, they would be required to recognize 80% of the changed amount of RWAs, stepping up to 85% in year 2, 90% in year 3, and 100% thereafter.

While the Capital Proposal would provide these 3-year transition periods, banking organizations and their counterparties typically adjust to regulatory changes prior to the final effective date. This is particularly true for changes to the regulatory capital requirements because capital instruments, assets and exposures can be outstanding for decades and banking organizations may be unwilling to accept the risk of having to increase their carrying costs at a later date. Therefore, we would expect that some banking organizations will begin pricing the effects of the Capital Proposal and G-SIB Surcharge Proposal into new transactions and considering how to address existing transactions once a final rule is issued.

Potential Impacts

If adopted, the Capital Proposal and G-SIB Surcharge Proposal would significantly impact the US banking system. As noted above, from an international perspective, the Capital Proposal would greatly increase the costs of operating a US banking organization, potentially impairing the competitiveness of US banking organizations. It would similarly increase the cost of foreign banks engaging in banking activity in the United States through an intermediate holding company. In this respect, the Capital Proposal is a continuation of the decades-long, global trend of ring fencing banking activity and protectionist measures designed to limit access by foreign banking organizations to the domestic US market.

If the Capital Proposal is adopted, banking organizations are also likely to adjust their activities to favor those with lower capital charges and either exit those with higher capital charges or pass increased pricing through to consumers and counterparties. Following the adoption of the 2013 Basel III revisions, there was a migration of activity out of the banking system (such as mortgage lending and trading) and a shift to lower-risk activities (such as investment advisory services).

As noted above, it is likely that some banking organizations will need to engage in capital markets activity, such as issuing new Tier 1 capital instruments, or to engage in strategic transactions, such as merging with over-capitalized banking organizations, to fill deficits and achieve economies of scale. We also expect to see more interest from banking organizations in transactions intended to mitigate the costs associated with the regulatory capital requirements (e.g., credit risk transfer trades, seller-financed off-balance sheet securitizations and securities financing transactions).

From a compliance perspective, many banking organizations will need to expend considerable resources to comply with the granular and data-intensive components of the Capital Proposal. In some cases, the Capital Proposal would require banking organizations to maintain duplicative data on certain exposures, such as credit exposures to subordinated debt or other financial institutions. There also will be a general need to collect and analyze massive quantities of data, the correlation of which to increased risk is questionable (as one commentator put it recently, “wheels within wheels”). These costs may lead to a general reduction in lending and trading activities by banking organizations and further migration of lending and trading activities to nonbank financial institutions. Further, the fact that the Capital Proposal deviates from the Endgame Standard in material ways could result in continued shrinkage and debanking by foreign banking organizations of their activities in the United States so as to avoid duplicative compliance costs.

The Capital Proposal purports to apply only to banking organizations with significant trading activity or total assets of $100 billion or more, but it will have at least two effects on smaller banking organizations that are not directly subject to it. First, smaller banking organizations will need to understand and apply the revisions to the market risk capital requirements. This is because the redefinition of the boundary between the trading book and banking book is a threshold issue in determining whether a banking organization has significant trading activity. Therefore, smaller banking organizations may suddenly be deemed to have significant trading activity solely due to the redefinition of this boundary. Second, smaller banking organizations often rely on larger banking organizations for certain products and services, such as hedging derivatives, securities brokerage, credit card processing, loan servicing, and billing/payment services. These services will be subject to the new operational risk capital charge, and we would expect the larger banking organizations to pass the increased cost of these services to smaller banking organizations.

One concern that the Capital Proposal is intended to address is the variability in models across banking organizations. However, in some circumstances, that variability may be driven by differences in the structure of banking organizations, not financial models. Further, one theme of the last decade is that regulators have sought to reduce risk in the banking system by eliminating outliers and encouraging homogeneity across organizations, such as by discouraging banking organizations with concentrated or niche business models or novel structures (e.g., banks owned by insurers). But by reducing heterogeneity, regulators may be increasing systemic risk. For example, if the regulators’ construction of one or more models in the Capital Proposal is faulty, that failure will affect all banking organizations. This herd risk can already be seen in the dysfunction in the primary dealer market, which is associated with the leverage ratios’ punitive treatment of government securities holdings. Although the Capital Proposal is intended to enhance financial stability by increasing capital requirements, the standardization of capital requirement could have the contrary impact.

Additionally, the Capital Proposal does not indicate how it will interact with the market risk parity exclusion in the Volcker Rule. That exclusion permits a banking organization to purchase or sell a financial instrument that does not meet the definition of trading asset or trading liability under the applicable reporting form as of January 1, 2020. While the Capital Proposal would revise the definitions of “trading asset” and “trading liability” in the regulatory capital requirements (and notes that corresponding revisions will be made to reporting forms), it would not revise the Volcker Rule or otherwise change the January 1, 2020, date in the Volcker Rule. Therefore, regulators may need to consider subsequent revisions to the Volcker Rule to maintain alignment between the scope of the prohibition against proprietary trading and the market risk parity exclusion.

1 FDIC, Board Meeting (July 27, 2023), https://www.fdic.gov/news/board-matters/2023/board-meeting-072723-open.html; Federal Reserve, Board Meeting (July 27, 2023), https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/boardmeetings/20230727open.htm. The US federal banking regulators consist of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (“Federal Reserve”), Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (“FDIC”).

2 See, e.g., Michelle Bowman, Responsive and Responsible Bank Regulation and Supervision (June 25, 2023) (“Banks pursue business strategies and offer products not despite capital requirements, but with the full knowledge and understanding of the capital allocations required to engage in that activity.”).

3 US banking organizations include national banks, state member and nonmember banks, federal and state savings associations, top-tier bank and savings and loan holding companies domiciled in the United States that are not subject to the Small Holding Company Policy Statement, except certain savings and loan holding companies that are substantially engaged in insurance underwriting or commercial activities, and US intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations.

4 For Category I and II banking organizations, Tier 1 capital requirements would increase by an estimated 19%; for Category III and IV US bank and savings and loan holding companies, an estimated 6%; for Category III and IV US intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations, an estimated 14%.

5 Letter to The Honorable Michael Barr from Chair Andy Barr and Ranking Member Bill Foster of the House Financial Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Monetary Policy (July 7, 2023); see also Letter to The Honorable Jerome Powell from Ranking Member Tim Scott and each Republican member of the Senate Banking Committee (July 21, 2023).

6 See our recent Legal Update discussing one of these alternatives: https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2023/05/residential-mortgage-loans-capital-relief-through-synthetic-securitization.

7 See also our Legal Update on this antitrust focus: https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2022/04/us-fdic-requests-comment-on-bank-merger-oversight-framework.

8 Press Release, BPI Response to Banking Agencies’ Basel Proposal (July 27, 2023).

9 See 54 Fed. Reg. 4209 (Jan. 27, 1989); see also Joseph Haubrich, A Brief History of Bank Capital Requirements in the United States, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland (Feb. 28, 2020).

10 12 C.F.R. §§ 3.10(a), 217.10(a), 324.10(a).

11 See our Legal Update on the 2013 revisions: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=ed44289a-37ba-4186-a55a-e401ef0a9a58.

12 12 C.F.R. §§ 3.10(e), 217.10(e), 225.8, 324.10(e).

13 Basel Committee, Basel III: Finalising Post-Crisis Reforms (Dec. 7, 2017).

14 See our Legal Update on the development of the Capital Proposal: https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2022/09/basel-endgame-intentions-announced-by-us-banking-regulators.

15 A Category I banking organization is a US G-SIB; a Category II banking organization is one that is not a US G-SIB but has over $700 billion in total assets or over $75 billion in cross-jurisdictional exposures; a Category III banking organization is one that is not included in Category I or Category II but has over $250 billion in total assets or greater than $75 billion in nonbank assets, off-balance sheet exposures, or weighted short-term wholesale funding; and a Category IV banking organization includes all organizations that are not in Category I, Category II or Category III but have over $100 billion in total assets.

16 Federal Reserve, Statement by Chair Jerome H. Powell (July 27, 2023), https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/powell-statement-20230727.htm.

17 This generally would include net unrealized gains or losses on available-for-sale debt securities, accumulated net gains or losses on cash flow hedges, amounts recorded in AOCI that are attributed to defined benefit postretirement plans resulting from the initial and subsequent application of the relevant accounting standards that pertain to these plans, and net unrealized holding gains or losses on held-to-maturity securities that are included in AOCI.

18 This refers to the punitive treatment of investments in the capital instruments of subsidiaries of banking organizations that are held by third parties, such as with certain state tax real estate investment trusts.

19 See our Legal Update on the Basel Committee action: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=3af5eb6d-0c0b-44ea-8f08-2d07ab8a1ae8.

20 When calculating the LTV ratio, the loan amount would be reduced as the loan amortizes. The value of the property generally would be maintained at the value measured at loan origination. A banking organization would not be permitted to recognize private mortgage insurance when calculating the LTV ratio.

21 The Capital Proposal does not directly change the risk-weighting of mortgage servicing rights but would impose a capital requirement on revenue from loan servicing for third parties through the operational risk capital requirements discussed below.

22 “CF dependent” refers to whether the banking organization’s exposure depends on the cash flows generated by the real estate (e.g., rental property).

23 “Transactor exposure” means a regulatory retail exposure that is a credit facility where the balance has been repaid in full at each scheduled repayment date for the previous 12 months or an overdraft facility where there has been no drawdown over the previous 12 months.

24 Currently, certain larger banking organizations calculate the amount of assets against which they must hold capital for credit risk under the advanced approaches. For these purposes, larger banking organizations have included US G-SIBs and other US banking organizations that have (i) $700 billion or more in average total consolidated assets or (ii) $75 billion or more in cross-jurisdictional activity and $100 billion or more in total consolidated assets, as well as certain subsidiaries of these banking organizations. Fewer than a dozen banking organizations are subject to the advanced approaches.

25 Currently, all banking organizations calculate the amount of assets against which they must hold capital for credit risk under a leverage ratio requirement. The leverage ratio requirement is a non-risk-based calculation that compares a banking organization’s Tier 1 capital to total assets (as reported on regulatory reports, which generally follow accounting standards). It does not include off-balance sheet items. Separately, certain larger banking organizations calculate a supplementary leverage ratio, which is based on the sum of on-balance sheet assets and off-balance sheet exposures, minus certain permitted deductions. The supplementary leverage ratio requirement generally applies to Category I, II and III banking organizations. Additionally, Category I banking organizations (i.e., US G-SIBs) are subject to an enhanced supplementary leverage ratio requirement, which requires they hold an additional buffer of leverage capital.

26 See FDIC Chair Martin Gruenberg’s remarks supporting the retention of leverage ratios in their current form: https://www.fdic.gov/news/speeches/2023/spjun2223.html.

27 See our earlier Legal Update on SA-CCR: https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/perspectives-events/publications/2018/11/us-banking-agencies-propose-changes-to-calculation/files/update_usbankingagenciesproposechanges_active_v3/fileattachment/update_usbankingagenciesproposechanges_active_v3.pdf.

28 See Michael Barr, Holistic Capital Review (July 10, 2023) (“With the revisions in risk-based capital requirements I mentioned above, the eSLR generally would not act as the binding constraint at the holding company level.”).

29 These positions are excluded from the standardized approach and advanced approaches for credit risk to avoid double-counting. Positions subject to a credit risk approach generally are known as “banking book” positions.

30 I.e., the position is held for the purpose of short-term resale, regular dealing or market making, with the intent of benefiting from actual or expected short-term price movements or to lock in arbitrage profits or to hedge a similar position.

31 The Capital Proposal generally would adopt the definition of trading desk from the Volcker Rule, although it is not a perfect fit because some activity covered by the market risk capital requirements currently may not require a banking organization to identify a trading desk. In any event, banking organizations are likely to expend considerable resources to control and document the market risk activities of trading desks under the Capital Proposal.

32 SIFMA, Explaining the Overlap Between the FRTB and the Global Market Shock (May 30, 2023). Certain elements of the G-SIB surcharge also overlap with the market risk capital and SCB requirements.

33 US regulators have indicated that the standardized approach implicitly considers operational risk in the calibration of risk weights for credit risk. See Basel Committee, RCAP Assessment – United States § 2.3.9 (Dec. 4, 2014) (“the Standardised Approach for credit risk that contains an implicit capital charge for operational risk”).

34 In a deviation from the Endgame Standard, the Capital Proposal would include insurance income when calculating the services component.

35 We thank the Bank Policy Institute (“BPI”) for providing data to support the estimation of RWAs for operational risk. See BPI, A Modification to the Basel Committee’s Standardized Approach to Operational Risk (May 4, 2022), https://bpi.com/a-modification-to-the-basel-committees-standardized-approach-to-operational-risk/.

36 Basel Committee, QIS 2: Operational Risk Data (May 4, 2001); Steve Marlin, Fed Preps Draft White Paper on Cyber Risk, Risk.Net (Apr. 5, 2019).

37 A banking organization generally does not calculate CVA risk for cleared transactions or for securities financing transactions for financial reporting purposes. Therefore, the Capital Proposal would not consider a cleared transaction or a securities financing transaction to be a CVA-risk covered position and would not extend the CVA risk-based capital requirements to such positions.

38 See our earlier Legal Updates on this issue: https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2022/04/shifting-sands-new-prudential-standards-for-larger-regional-banks-under-consideration-by-us-occ; https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2022/10/us-banking-regulators-solicit-comment-on-resolutionrelated-obligations-for-larger-regional-banks.

39 See our Legal Updates on these developments: https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2022/12/crypto-exposure-standards-finalized-by-basel-committee; https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2022/12/hidden-in-plain-sight-bcbs-discovers-climate-capital-and-liquidity-requirements-in-existing-rulebook.