(Bloomberg) — Keir Starmer is teeing up plans for billions of pounds worth of new private investment in Britain in the first few months of a Labour government — a surge that the opposition party hopes is large enough to meet its ambitious growth goals and avoid tax hikes if it wins next week’s election.

Rachel Reeves, who is set to become Britain’s first woman chancellor of the exchequer on July 5 if polls are correct, has for months been working to spark investors’ interest in projects that are central to Labour’s manifesto, people familiar with the matter said. Areas of focus include the push into green energy, ramping up house-building and improving public transport and the roads.

The plan involves creating new financial instruments to stimulate demand from institutional investors, as well as considering how the government can take on some of the risk of private investments in key projects, according to the people, who requested anonymity discussing plans for after next week’s election. The people declined to detail the specific investments they are expected to announce.

A Labour spokesperson declined to comment.

Amid forecasts for tepid growth this year and next after a short recession in 2023 — and hemmed in by tight public finances as well as their own pledges on taxation — Starmer and Reeves see private finance as an essential source of funding for national infrastructure projects, the people said. Their calculation is it’s only through working closely with investors that they can stimulate the sort of growth needed to be able to rebuild public services crumbling after more than a decade of under-investment under the Conservatives.

“It is absolutely right that we want investors to come alongside that government money,” Starmer said in the final televised debate before the July 4 election on Wednesday evening. “We’ve been talking to global investors for the best part of two years, saying that if we put down this money set out in our manifesto, if you come alongside it and put down many more billions of pounds, so that in partnership with the government we can make the changes we need.”

The plans hark back to the last Labour government in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, private finance initiatives and public-private partnerships were expanded. They’ve since come in for criticism due to questions over their value-for-money, the quality of privately-delivered projects and arrangements used to keep debt off the government’s balance sheet.

Labour has said it will stage a global investment summit in its first 100 days in office, and has been holding meetings with what it calls its British Infrastructure Council to discuss with UK-based and international investment firms how it can unlock private capital. Attendees of the meetings have included representatives from BlackRock, Lloyds Banking Group, Santander, HSBC, Phoenix Group and Fidelity International, among others.

Those conversations have been constructive and Labour is confident it would be able to quickly announce significant amounts of new investment shortly after an election win, centered around the “missions” Starmer has said would be a priority for a Labour government, according to the people.

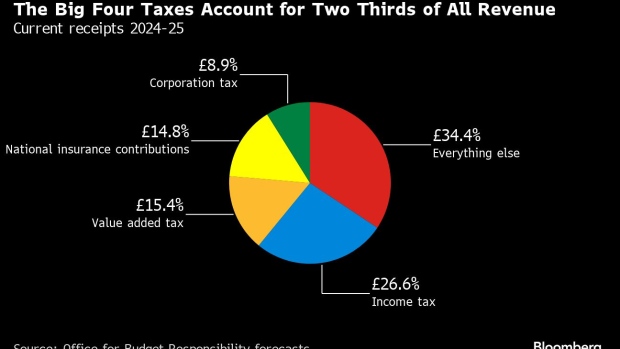

Over the course of the next parliament, the party hopes that amount will rise to the tens of billions of pounds, allowing them to secure improvements to public projects without breaking the pledge not to raise income tax, national insurance, corporation tax or value-added tax.

The opposition party, which is seen as highly likely to oust Rishi Sunak’s Tories nest week, has struggled to convince economists that it can fix problems with Britain’s stagnant economy, ailing public services and infrastructure without raising taxes.

According to Bloomberg Economics, the next administration needs to find £20 billion ($25.3 billion) of revenue-raisers to deliver current spending plans. Analysis by economists Dan Hanson and Ana Andrade on Wednesday expressed skepticism about Starmer’s hopes for a “growth miracle.”

Private finance is seen as one of the ways of squaring that circle, according to party officials. Bloomberg previously reported how Labour was planning to borrow to invest in British industry with the aim of increasing private sector investment. Every £1 of public money invested in Labour’s proposed National Wealth Fund would have to raise at least £3 of private capital, Reeves has said.

There’s precedent for such “crowding in,” since Britain’s state-owned Green Investment Bank saw similar returns before it was sold by the Conservative government in 2017. Still, International Monetary Fund research points to a much more modest return of around 50 pence in private investment for every £1 from the state.

Private sector money is likely to mainly come from big UK banks through syndicated loans, insurers and pension funds, Bloomberg previously reported, with Labour holding talks with the likes of HSBC and BlackRock on investing in skills to retrofit homes with insulation and other energy-saving measures as well as ways to make affordable housing viable for developers across the country.

One Labour official joked that the party would be getting BlackRock to rebuild Britain. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink last year told the Wall Street Journal that Starmer had shown “real strength as a moderate” in comparison to his left-wing predecessor as Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn. “I believe that’s a measurement of hope,” Fink said of a possible Starmer administration.

–With assistance from Katherine Griffiths and Andrew Atkinson.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.