These FAQs provide details on pandemic-related measures that ECB Banking Supervision took in 2020 and 2021. On 10 February 2022 the ECB announced the end of the last temporary relief measures still available to banks, hence confirming the return to normality under the initially envisaged timeline.

Section 1 – Relief measures regarding asset quality deterioration and non-performing loansSection 2 – Relief measures regarding the operational aspects of supervisionSection 3 – Relief measures regarding capital and liquidity requirementsSection 4 – Restrictions on dividends and variable remunerationSection 5 – Other measures

Section 1 – Relief measures regarding asset quality deterioration and non-performing loans

In March 2020 you announced flexibility when implementing the ECB Guidance on non-performing loans (NPLs). Did you consider forbearance for NPLs? Did you look at other ways to mitigate the deterioration of asset quality, for example with regard to IFRS 9?

The ECB Guidance on NPLs already embedded flexibility and case-by-case assessments by Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs).

In exercising flexibility, the ECB sought to strike the right balance between helping banks absorb the impact of the current downturn, on the one hand, and maintaining the correct risk identification practices and risk management incentives, on the other, as well as ensuring that only sustainable solutions for viable distressed debtors were deployed.

It remained crucial, in such times of distress, to continue identifying and reporting asset quality deterioration and the build-up of NPLs in accordance with the existing rules, so as to maintain a clear and accurate picture of risks in the banking sector. At the same time, flexibility had to be deployed to help banks absorb the impact of credit risk developments and mitigate the procyclicality of that impact.

Against the backdrop of these guiding principles, and to complement the case-by-case flexibility embedded in the ECB Guidance on NPLs and in the Addendum, the ECB took the additional actions described below.

In relation to all exposures that benefit from government guarantees issued by Member States in the context of public interventions relating to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the ECB, within its own remit, and within the context of the ECB Guidance on NPLs and the Addendum, extended flexibility on the automatic classification of obligors as unlikely to pay when institutions call on the coronavirus-related public guarantees, as allowed under the Guidelines on the application of the definition of default issued by the European Banking Authority[1].

The preferential treatment foreseen for NPLs guaranteed or insured by Official Export Credit Agencies was extended to non-performing exposures that benefit from guarantees granted by national governments or other public entities. This ensured alignment with the treatment provided in Regulation (EU) 2020/873 (the CRR “quick fix”)[2]. Concretely, this meant that banks would face a 0% minimum coverage expectation for the first seven years of the NPE vintage count.

The ECB also extended flexibility to the NPL classification of exposures covered by qualifying legislative and non-legislative moratoria, following the EBA guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the coronavirus crisis[3], as amended. More precisely, the ECB complied with the abovementioned EBA guidelines. Paragraph 17(bis) of these guidelines requires significant banks to notify the ECB of how they assess creditors’ creditworthiness in the context of moratoria; the ECB expected banks to do this when responding to the letter of 4 December 2020 on “Identification and measurement of credit risk in the context of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic”.

Accounting standards, and their implementation, do not fall within the remit of ECB Banking Supervision, which can take very limited action in this regard. In a letter to banks under its supervision dated 1 April 2020, the ECB provided guidance to mitigate volatility in banks’ regulatory capital and financial statements stemming from IFRS 9 accounting practices, including on the use of forecasts to avoid excessively procyclical assumptions in expected credit loss (ECL) estimations. Given that the IFRS 9 provisions must be based on macroeconomic forecasts and that, particularly in times of pronounced uncertainty, IFRS 9 model outcomes may be excessively variable and procyclical, the ECB:

- Encouraged those banks under its supervision that had not already done so to fully implement the transitional IFRS 9 arrangements foreseen in Article 473(a) of the CRR. The ECB stood ready to process in a timely fashion all applications received in this context.

- Expected banks to consider whether a top-down collective approach could be applied to estimate a portion of the portfolio for which credit risk had increased significantly. This was especially important in times where information at loan level was not yet available to banks.

- Expected, within the framework provided by international accounting standards, that banks gave greater weight to long-term macroeconomic forecasts evidenced by historical information when estimating long-term expected credit losses for the purposes of IFRS 9 provisioning policies. This appeared particularly important where banks faced uncertainty in generating reasonable and supportable forecasts. In producing such forecasts, banks had to take into account the relief measures granted by public authorities – such as payment moratoria.

- Expected banks to consider ECB publications on macroeconomic projections in applying IFRS 9 provisioning policies.

Adopting transitional IFRS 9 implementation measures allowed banks to filter out from their prudential capital a large part of the additional IFRS 9 volatility from 2020 until the end of the planned transitional period. The measures proposed under (2), (3) and (4) were also intended to help mitigate procyclicality in banks’ published financial statements.

The ECB welcomed the extension of IFRS 9 transitional arrangements introduced by Regulation (EU) 2020/873 (the CRR “quick fix”). This legislation extended the IFRS 9 transitional arrangements by two years, and institutions were allowed to fully add back to their Common Equity Tier 1 capital any increase in expected credit loss provisions that they recognised in 2020 and 2021 for their financial assets that were not credit-impaired, as compared to end-2019. In addition, a temporary prudential filter that neutralised the impact of the volatility in central government debt markets on institutions’ regulatory capital during the coronavirus pandemic was introduced.

Did you also revise your expectations for the stock of NPLs?

In the context of the financial turmoil triggered by the coronavirus outbreak, banks were to be supported as they provided solutions to viable distressed customers. The stock of NPLs accumulated prior to the outbreak was not the focus of our mitigation measures in reaction to the coronavirus. However, the ECB was fully aware that market conditions had the potential to make the agreed reduction targets difficult to attain and somewhat unrealistic. In this vein, the JSTs were fully flexible when discussing the implementation of NPL strategies on a case-by-case basis.

Regarding the submission of updated NPL strategies, the ECB announced on 28 July 2020 its decision to postpone the deadline for submission by another six months, to end-March 2021, to provide banks with additional time to better estimate the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on asset quality and enable more accurate planning.

Banks were nonetheless still expected to continue with the active management of their NPLs and any foreclosed assets.

Did you provide guidance regarding the operational management of asset quality deterioration during this time?

In order to be able to provide support to viable distressed borrowers, banks need to ensure that they have effective risk management practices and sufficient operational capacity in place. Therefore, in a letter dated 28 July 2020 to all banks under its direct supervision, the ECB provided a number of high-level supervisory expectations, along with more specific operational elements, which banks were expected to follow. As a follow-up to this letter, JSTs have been engaging with banks to discuss their risk management practices in the light of these expectations, focusing on any gaps identified.

How did the letter “Identification and measurement of credit risk in the context of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic”, published on 4 December 2020, relate to previous communications from the ECB?

The purpose of the letter to banks of 4 December 2020 was to provide banks with additional guidance on credit risk identification and measurement in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, the ECB’s supervisory activities had identified heterogeneous practices across significant banks with regard to the implementation of the letter of 1 April 2020. The letter published on 4 December 2020 therefore served to further clarify what the ECB considered to be sound risk management policies and procedures. Further background is available in this blog post on credit risk management dated 4 December 2020. See also this follow-up blog post dated 19 July 2021.

The letter published on 28 July 2020 complemented the above communication, setting out supervisory expectations with respect to operational preparedness to deal with distressed debtors.

Section 2 – Relief measures regarding the operational aspects of supervision

You announced in March 2020 that JSTs would discuss with individual banks a more flexible approach to supervisory processes, timelines and deadlines. What did this entail?

To alleviate the supervisory burden for banks during stressed times, the ECB clarified on 20 March 2020 that it had decided to do the following:

- Postpone, by six months, the existing deadline for remedial actions imposed in the context of on-site inspections, TRIM investigations and internal model investigations.

- Postpone, by six months, the verification of compliance with qualitative SREP measures.

- Postpone, by six months, the issuance of TRIM decisions, on-site follow-up letters and internal model decisions not yet communicated to institutions, unless the bank explicitly asked for a decision because it was seen as beneficial to the bank.

- Permit banks with stable recovery plans to submit only the core elements (indicators, options, overall recovery capacity) of their 2020 plans, focusing on the current coronavirus stress and ensuring that the plans could be implemented effectively and in a timely manner if needed. Banks were also permitted, where applicable, to address only the key deficiencies identified in the 2019 plans.

In addition to the above, in 2020 the ECB did not undertake comprehensive information gathering relating to the LCR for the products and services referred to under Article 23 of the LCR Delegated Regulation[4] for which the likelihood and potential volume of liquidity outflows are material. However, banks were reminded that they were still required to properly estimate outflow rates for these products and services based on their own methodologies, unless otherwise determined by the ECB in the past, and that such estimates should reflect the assumption of combined idiosyncratic and market-wide stress as referred to in Article 5 of the LCR Delegated Regulation. In that regard, these estimates also had to reflect experiences made during the recent stress period.

Taking into account the recent economic and financial developments and the gradual return to normality at most banks, the ECB did not further postpone the deadlines for remedial actions imposed in ECB decisions and operational acts, including in relation to on-site inspections, TRIM investigations and internal model investigations. Similarly, it resumed the supervisory processes for adopting new decisions on TRIM, on-site follow-up letters and internal model decisions from October 2020.

The measures taken regarding recovery plans did not apply to deadlines, meaning that banks still had to submit their 2020 recovery plans by the existing deadlines.

In March 2020, you postponed the verification of compliance with qualitative SREP measures by six months. Was there any further postponement?

No. Instead, the ECB decided to resume the process of verifying compliance with qualitative SREP measures. Considering the pragmatic approach to the SREP mentioned in the blog post published in May 2020 and taking into account the requirements applicable to the banks, the ECB decided as a general rule to not issue SREP decisions for the 2020 SREP cycle. Nevertheless, based on the assessment conducted in 2020, unless justified by exceptional circumstances affecting individual banks, observations and concerns were conveyed to banks as qualitative recommendations upon conclusion of the SREP.

Section 3 – Relief measures regarding capital and liquidity requirements

You have allowed banks to operate below their P2G level until end-2022 and frontloaded the rules on the composition of P2R that were originally scheduled to come into force in 2021 with CRD V. Concretely, how much capital relief has this provided?

We announced in the press release of 20 March 2020 that a release of the full Pillar 2 Guidance (P2G) buffer would make around €90 billion of Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital available to banks under direct ECB supervision. With the immediate implementation of the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD V) rules on the composition of Pillar 2 Requirements (P2R), which are less stringent than the composition previously requested by the ECB, around €30 billion of additional CET1 capital was added to the relief. The two measures combined provided banks with aggregate relief of roughly €120 billion of CET1 capital. Overall, this provided significant room for banks to absorb losses on outstanding exposures without triggering any supervisory action.

As announced in the press release of 20 March, the ECB estimated that the capital released by the two measures could enable banks to potentially finance up to €1.8 trillion of loans to households, small businesses and corporate customers in need of extra liquidity, taking into account that the average risk of lending to households, small businesses and corporates would most likely increase as a result of the shock. Thus, even in the most adverse scenarios, the lending capacity released by the measures remained very substantial.

These estimates did not take into account the beneficial effects of the public guarantees provided by various Member States in favour of household and/or corporate borrowers. As public guarantees substantially reduce the regulatory capital cost of lending and the amount of provisions that banks need to take against expected losses, such public measures increase the lending potential of banks.

Since March 2020 banks have issued more Additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruments, thereby increasing the CET1 capital relief stemming from the change in P2R composition from €30 billion of CET1 capital initially to €42 billion of CET1 capital as at 30 September 2020. On that date, the capital relief reached approximately €200 billion of CET1 capital, taking into account the aforementioned €42 billion, P2G relief of about €90 billion, macroprudential buffers relief of about €20 billion, €28 billion of dividends withheld in 2020 and €25 billion of provisions added back to CET1 capital under the IFRS 9 transitional arrangements.

How did allowing banks to operate below their P2G help the economy?

In March 2020 you said banks could make full use of their capital buffers, including the capital conservation buffer (CCB). Did this mean that you expected banks’ capital losses to reach levels that would deplete the CCB buffer? What are the implications if that happens?

The ECB’s indication that banks could also use the capital conservation buffer was not linked to a specific expectation regarding capital losses. The ECB reminded banks under its supervision that, in those difficult times, all capital buffers including the CCB could be used to withstand potential stress, in line with the initial intentions of the international standard setter on the usability of the buffers [Newsletter on buffer usability, 31 October 2019]. Having said that, as indicated in the notes to the press release of 12 March 2020, in the case of banks’ capital falling below the combined buffer requirement (CCB, CCyB and systemic buffers), banks could make distributions only within the limits of the maximum distributable amount (MDA) as defined by EU law.

The ECB does not have any discretion to waive the application of automatic restrictions on distributions that are set out in EU law. However, the ECB’s decision to frontload the CRD V rules on the composition of P2R reduced the MDA trigger level for banks with enough AT1/T2 capital.

This said, as part of its full buffer flexibility applicable until end-2022, the ECB committed to taking a flexible approach to approving capital conservation plans that banks are legally required to submit if they breach the combined buffer requirement.

You allowed banks to operate with a liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) below the general minimum level of 100% until the end of 2021. What did this imply and what is the state of play as of 1 January 2022?

The ECB clarified in its press release of 12 March 2020 that substantial use could be made of LCR liquidity buffers in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, even if this resulted in the LCR falling significantly below the general 100% minimum level. By doing so, the ECB effectively confirmed – ex ante – that the outbreak of the pandemic was in fact a situation of stress for which the applicable regulation explicitly allowed banks to use their liquidity buffers[5]. The ECB clarified in its press release of 28 July 2020 that it would not expect banks to replenish their liquidity buffers before the end of 2021.

In view of banks’ stable and comfortable liquidity positions, as well as the abundant liquidity available in the banking system, there was no need to extend this liquidity relief beyond the end of 2021. Therefore, the ECB announced in its press release of 17 December 2021 that it expected all banks to comply with the general LCR minimum level of 100% as of 1 January 2022.

This does not reduce or limit the flexibility embedded in the applicable regulation: during times of stress banks may still make use of their liquidity buffers, even if this results in the LCR falling below the general minimum level of 100%. In such cases the ECB will, however, carefully examine the extent to which they correspond to actual periods of stress as referred to in the regulation.

You have allowed banks to temporarily operate below their P2G. Until when does this apply?

The ECB announced in its press release of 10 February 2022 that it saw no need to allow banks to operate below the level of capital defined by their Pillar 2 Guidance beyond December 2022.

The ECB had previously announced in its press release of 12 March 2020 that banks were allowed to operate below their P2G until further notice, and it had committed in the press release of 28 July 2020 to maintaining this full buffer flexibility until at least end-2022.

By drawing down their capital buffers, banks were able to retain their ability to continue lending to households and businesses through the recent period of stress. Other things remaining equal, maintaining support for the real economy also reduces the level of credit losses affecting the banking system, thereby helping to mitigate the downward pressure on banks’ solvency ratios.

The ECB cautiously took into account the evolution of economic conditions and the credit cycle before requesting that banks replenish their Pillar 2 Guidance buffer. The ECB committed to not doing this too early in the capital cycle. On 10 February 2022, a limited number of banks were operating below the level of capital defined by their Pillar 2 Guidance. The ECB expects them to operate above the levels defined by their new Pillar 2 Guidance as of the beginning of 2023. If it is challenging for a bank to fully replenish its Pillar 2 Guidance buffer within this timeline, the bank should notify and present to the ECB a capital plan setting out credible capital trajectories.

The 2021 EBA Stress Test informed the setting of P2G levels. Did it impact P2G levels?

Indeed, as explained in the press release of 30 July 2021, the quantitative impact of the adverse stress test scenario is a key input when supervisors determine the level of P2G. However, the ECB does not intend the updated P2G levels to be fully met by banks before the date when banks are expected to again meet their P2G (see previous question). In particular, the ECB intends to give banks sufficient time to replenish their capital in cases of increased P2G levels. The ECB has notified banks of their updated P2G, allowing them to design appropriate capital plans in a timely manner.

What were the implications of the ECB stance on the buffer/P2G use for less significant institutions?

The ECB expects national competent authorities to apply the same treatment to less significant institutions as the ECB is applying to significant institutions.

Section 4 – Restrictions on dividends and variable remuneration

You have decided to return to a bank-by-bank assessment of capital and distribution plans. Why?

The recommendation for banks to suspend and then to curtail their distributions was an exceptional measure intended for exceptional circumstances. We had previously expressed our intention to go back to a bank-by-bank assessment in the absence of any materially adverse developments. The June 2021 macroeconomic projections confirmed the economic rebound and pointed to a further reduction in the level of economic uncertainty, improving the reliability of banks’ capital projections when compared to the beginning of the pandemic. These elements allowed us to repeal the recommendation with effect from the end of September 2021. Supervisors have gone back to the previous supervisory practice of discussing capital trajectories and dividend or share buy-back plans with each bank in the context of the normal supervisory cycle.

Was it prudent to let banks pay dividends while their balance sheets and NPL ratios still did not fully reflect the impact of the pandemic?

We specifically focused on the adequacy of credit risk processes in order to identify weaknesses in the identification, classification and measurement of credit risk, as explained in the July 2021 blog post on credit risk controls. Our aim was to prevent a build-up of vulnerabilities, as weak controls and processes have resulted in undue increases in problematic loans in previous recessions.

Even though the full scale of the issues related to COVID-19 had not yet materialised, our review helped banks deal with upcoming challenges, including a potential increase in non-performing exposures on their balance sheets, as support measures expire. Supervisors have maintained close scrutiny of credit risk developments related to the impact of the pandemic. We react using our supervisory toolkit where we see any build-up of risks. We do not see our dividend recommendation as being part of our standard supervisory toolkit.

Which criteria are you looking at to assess banks’ dividend plans?

We expect banks to communicate early with their supervisors about their distribution plans before announcing them to the markets. We see the assessment of capital trajectories as an important element in the ongoing supervisory dialogue; dividend and share buy-back plans are an important element of this assessment along with other management actions (e.g. capital increases, management of risk-weighted assets, structural measures to improve profitability). Supervisors thoroughly assess banks’ plans to distribute dividends and conduct share buy-backs on an individual basis in the context of the supervisory cycle after a careful forward-looking assessment of capital plans.

In assessing banks’ dividend plans, supervisors take into account the resilience of banks’ capital generation capacity, the quality of their capital planning framework (including the management of cliff effects from transitional arrangements and the reliability of the underlying macroeconomic assumptions), and the potential impact of a deterioration in the quality of exposures, including under adverse scenarios. Banks with robust capital trajectories are those that can demonstrate that uncertainty around adverse asset quality developments in the coming years can be covered by sufficient capital generation capacity or credible management actions.

Stress test results are also considered. Supervisors use the stress test results to detect vulnerabilities in banks’ risk profiles and to inform the assessment of distribution plans. At the same time, we do not see the stress test results as being a test to automatically determine whether and how much banks should remunerate their shareholders, as regulatory mechanisms such as the maximum distributable amount (MDA) are already designed for this purpose.

What are the ECB’s expectations on variable remuneration after 30 September 2021?

In December 2020 we sent a letter to banks to outline our expectation that banks adopt extreme moderation with regard to variable remuneration over the same period foreseen for limiting dividends and share buy-backs (until 30 September 2021). We then carefully monitored banks’ pandemic-related decisions on remuneration: we were broadly satisfied with the measures undertaken, as several banks adjusted their plans (such as reduction/cancellation of the variable remuneration bonus pool, deferral for a longer period of time and payment of variable remuneration in instruments). We also saw a broader improvement by banks in their remuneration policies and practices; our supervisory action further spurred banks in that direction.

The June 2021 macroeconomic projections pointed to a nascent economic recovery and a further reduction in the level of economic uncertainty. Against this background, banks are no longer expected to exercise extreme moderation in their remuneration policies in relation to the COVID-19 crisis.

In line with the EU regulatory framework, the ECB expects banks to adopt a prudent, forward-looking stance when deciding on their remuneration policy, as communicated to banks before the pandemic (SSM-2020-016). Institutions should carefully weigh the potentially detrimental impact of remuneration on the objective of maintaining a sound capital base. Such supervisory expectations are guided by the principle of proportionality as situations vary considerably, depending on factors such as the banks’ remuneration practices, business model and size. Our expectations apply to both significant supervised entities and individual institutions that are not part of a significant supervised group.

Section 5 – Other measures

In September 2020 you granted leverage ratio relief to banks – i.e. you allowed banks to temporarily exclude central bank exposures from their leverage ratio. In June 2021 you extended this measure until March 2022. What exactly is the leverage ratio and why is it a backstop? What did the leverage ratio relief do?

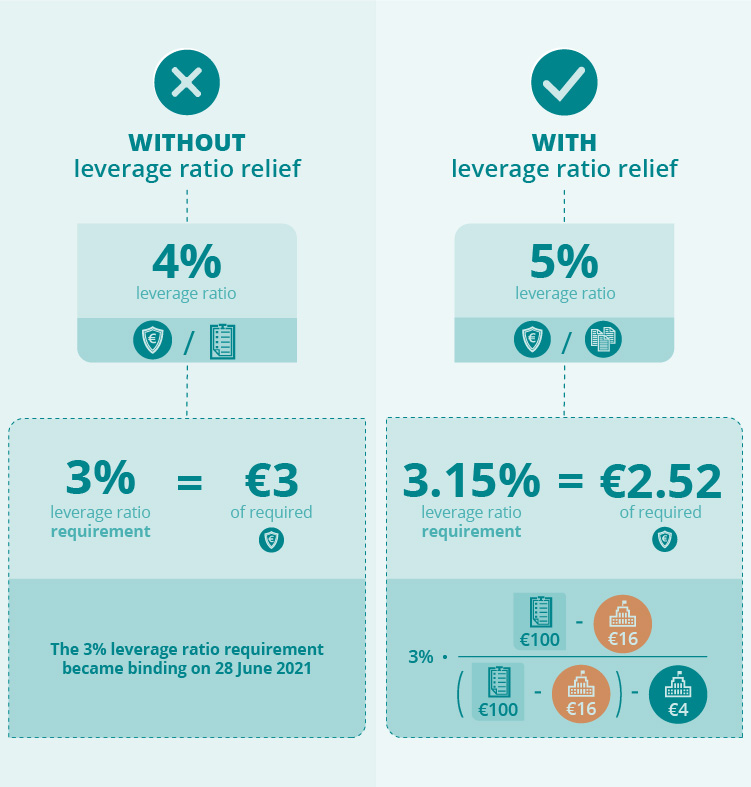

The leverage ratio shows the relationship between a bank’s Tier 1 capital and its total exposure measure. The total exposure measure includes the bank’s assets and off-balance-sheet items, irrespective of how risky these are. Because the leverage ratio is not dependent on risk, the 3% leverage ratio requirement serves as a simple, non-risk-based backstop to risk-weighted capital requirements. The 3% leverage ratio requirement became binding for banks on 28 June 2021.

The leverage ratio relief that the ECB announced in the press release of 18 June 2021 meant banks could exclude certain central bank exposures from their total exposure measure (i.e. from the denominator of the leverage ratio) until March 2022. This press release specified that banks that elected to use this extension should nevertheless plan to timely maintain sufficient capital in view of the expiry of the prudential exemption.

Only central bank exposures that were accumulated after the beginning of the pandemic effectively benefited from this leverage ratio relief. The level of resilience provided by the leverage ratio before the pandemic was therefore maintained. This was done via an upward recalibration of the 3% leverage ratio requirement: a bank which decides to exclude central bank exposures from its total exposure measure needs to recalibrate its 3% leverage ratio requirement, meaning its leverage ratio requirement will not be 3% any more but a bit higher.

Banks had a choice as to whether they wanted to use this relief measure – i.e. they did not necessarily have to exclude the central bank exposures and recalibrate their leverage ratio.

How did the upward recalibration of the 3% leverage ratio requirement work in practice?

The recalibration ensured that only increases in banks’ central bank exposures after end-2019 would in practice lead to leverage ratio relief. In the example below, the bank would recalibrate its 3% leverage ratio requirement to 3.15%. This way, only central bank exposures accumulated after the beginning of the pandemic (€16 in the example below) effectively benefited from the leverage ratio relief[6].

Why did you choose 31 December 2019 as the reference date for the recalibration of the 3% leverage ratio requirement?

The reference date chosen for this recalibration was 31 December 2019, as it was the last end of quarter before the pandemic, based on the start date of the supervisory and monetary policy measures implemented[7] in March 2020.

You have not extended this leverage ratio relief beyond March 2022. What does this mean for banks?

In its press release of 10 February 2022, the ECB announced that it saw no need to extend beyond March 2022 the supervisory measure that allowed banks to exclude central bank exposures from the leverage ratio.

Banks have ample headroom above the leverage ratio requirement: at end-September 2021, the aggregate leverage ratio of banks under direct ECB supervision stood at 5.88% (after 51 banks had excluded a total of €2.1 trillion in central bank exposures from the denominator of the leverage ratio). If these exposures had been included, the aggregate leverage ratio of banks under direct ECB supervision would have been 5.40%.

From 1 April 2022, the leverage ratios of all banks include central bank exposures again and the leverage ratio requirement is again 3% for all banks (cf. question above: “How did the upward recalibration of the 3% leverage ratio requirement work in practice?”).

Annex:

BCBS Statement: https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs_nl22.htm

[BCBS statement extract]

While each of these buffers seeks to mitigate specific risks, they share similar design features and are all underpinned by the following objectives:

- absorbing losses in times of stress by having an additional overlay of capital that is above minimum requirements and that can be drawn down; and

- helping to maintain the provision of key financial services to the real economy in a downturn by reducing incentives for banks to deleverage abruptly and excessively.

The Committee continues to be of the view that banks and market participants should view the capital buffers set out in the Basel III framework as usable in order to absorb losses and maintain lending to the real economy. In practice, the Basel capital buffers are usable in the following manner:

- banks operating in the buffer range would not be deemed to be in breach of their minimum regulatory capital requirements as a result of using their buffers;

- banks that draw down on their buffers will be subject to the automatic distribution restriction mechanism set out in the Basel III framework; and

- supervisors have the discretion to impose time limits on banks operating within the buffer range, but should ensure that the capital plans of banks seek to rebuild buffers over an appropriate timeframe.