By David G. Blanchflower, Professor of Economics, Dartmouth College, and Alex J. Bryson, Professor of Quantitative Social Science, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London

By David G. Blanchflower, Professor of Economics, Dartmouth College, and Alex J. Bryson, Professor of Quantitative Social Science, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London

Arecession is a period of severe economic downturn marked by falls in output. Determining the start date of a recession is tricky and a bit of an art form. Usually, economists characterize it as two successive quarters of negative gross domestic product (GDP) growth. Rising unemployment rates usually accompany such downturns. In the United States, recessions are called by NBER’s (National Bureau of Economic Research’s) Business Cycle Dating Committee. Since 1992, committee members have called recessions in 2001, 2008 and 2020. They called the start dates as March 2001 (November 2001), December 2007 (December 2008) and February 2020 (June 2020)—the dates when the NBER actually called them as being the starts of the recessions are shown in parentheses. The calls for the first two recessions were not based on two successive quarters of economic downturn, as there were intervening positive quarters. Hence, in our analyses discussed below we identify a recession with two negative quarters of growth out of three for the United States.

One reason recessions are hard to predict is that, at least until the past decade or so, they were quite rare. We examined the last 125 quarters of quarterly GDP growth in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and France between second-quarter(Q2)1991 and second-quarter(Q2)2022, looking for quarters of negative growth—either two successive quarters or two out of three. Here’s what we found:

As an example of the rarity of recessions in the UK and Canada, there was not a single quarter of negative growth in the first 65 quarters of our study until the second quarter of 2008. All four countries experienced negative growth in 2008 and 2009, during the Great Recession, and in the first two quarters of 2020 as COVID-19 hit. France also had negative growth in Q42019. Overall, we counted four recessions in the US and France and three in Canada and the UK over this 30-year period. France had a recession from Q41992 to Q11993 but nothing until Q22008. In the US, there was a recession in 2001 and again during the Great Recession.

The problem with downturns is that revisions to GDP tend to be large, making it harder to call the start of a recession correctly. Estimates are initially largely based on forecasts and revised as more data becomes available. These revisions can occur for decades. The initial estimates are often biased upwards, as it takes a while for the weak data to roll in. In the UK, the first estimate for Q22008 was +0.2 percent. In fact, it wasn’t clear that the Great Recession had started in the UK in Q22008 until June 2009, when the estimate was revised to a negative number. At the time of writing, the estimate for Q22008 has been revised to -0.5 percent.

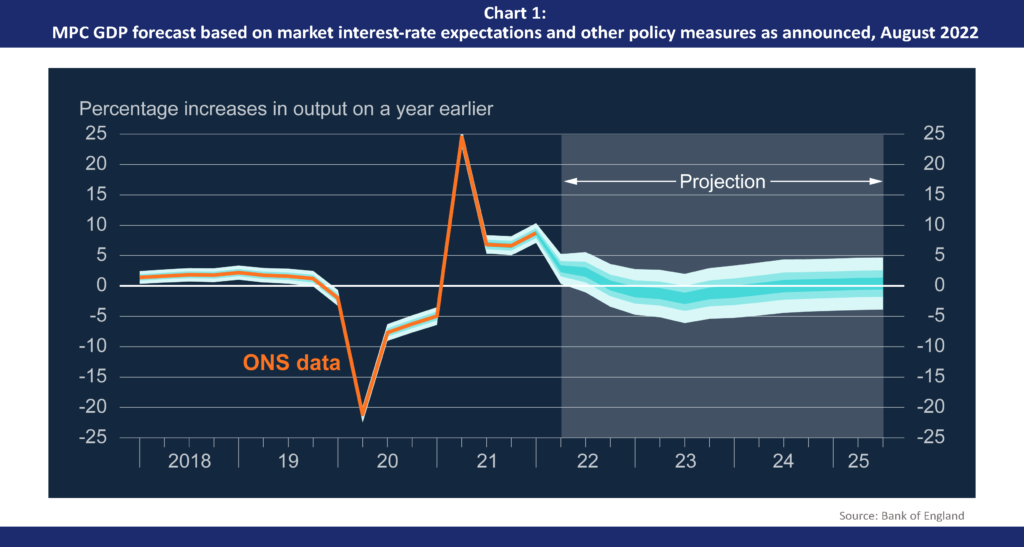

These GDP-growth data explain what happened in the months and years after the event; the difficulty for policymakers is predicting recessions before they happen. The complication in making a forecast is that a view has to be taken on the potential for data revisions in the past to occur. This is particularly problematic at turning points. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England (BoE) includes a “backcast” in its GDP forecasts on what it expects to happen to GDP over the next three years of revisions, which is illustrated in Chart 1 for August 2022. The backcast has error bands around it that narrow over time as there are more opportunities for revision. In contrast, the forecast error bands widen as time moves forward because it is harder to forecast further into the future. Being wrong in the backcast makes it hard to be right in the forecast or to know where things stand when the forecast is made. The MPC is currently forecasting a recession at market rates lasting five quarters, followed by two quarters of zero and five quarters of 0.1 percent.

Given that recessions are rare events, some economists and central bankers have argued that nobody should expect them to be spotted. Some have even argued that if they had been spotted, it wouldn’t have made any difference. This makes no sense. During downturns, the evidence indicates that the labor market also turns down and the unemployment rate rises. It usually takes a while for the unemployment rate to pick up at turning points. A major job of central banks is to stop recessions, spot them before they happen, and try to reduce both their amplitude and duration. What central banks should do is look at qualitative data that is timely and isn’t revised.

We have shown in a couple of our papers that this is possible using data from what we call “the economics of walking about”. We ask consumers and firms for their economic and financial expectations for the months ahead to spot recessions. This has better predictive power than economic forecasters. We call recessions six to twelve months before they happen. We collect the views of consumers and firms on what they see coming, and these forecasts turn out to be very accurate (Blanchflower, 2008)1.

We have noted that in the United States, the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee called recessions in 2001 and 2008; it also did so in January 1980, July 1981 and July 1990. In Blanchflower and Bryson (2022b)2, we show that by using data on declines in consumer expectations from the Conference Board and the University of Michigan, it is possible to predict recessions many months before they happen. There have been no instances when these forecasted recessions didn’t happen.

We forecast recessions by seeing if the Conference Board’s Expectations Index (consumers) falls by at least 10 points in a 12-month period. We report the extent of the drop in 2007 in the Expectations Index in Column 1 below in eight major US states. The majority of the low points of these series occurred in November or December 2007 and started falling from peaks between February and August 2007. Beside it, we report comparable estimates for the peaks that occurred in 2021 and then the low points that mostly occurred in July 2022. The drop in expectations is much greater in 2022 than in 2007 at the start of the Great Recession. They suggest a recession in 2022.

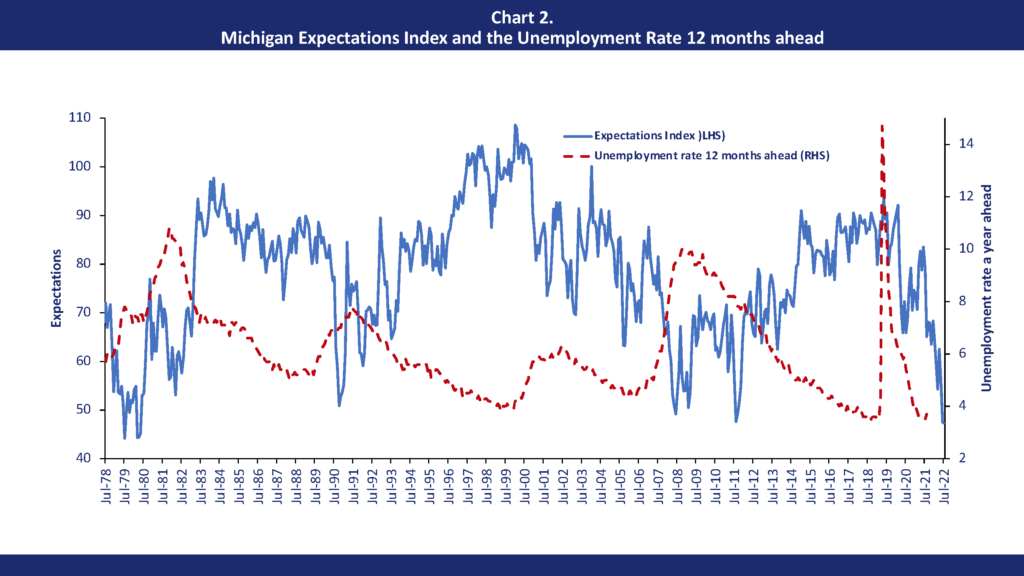

In the chart, we show the relationship between the University of Michigan Consumer Expectations index—a higher number means higher expectations—and the unemployment rate a year ahead from 1991. The index started falling sharply in October 2000, consistent with the recession in March 2001. It also started falling sharply again in January 2007. Of particular note is that the index fell from 79 to 65 between July and August 2021, and the unemployment rate rose from 3.5 percent in July 2022 to 3.7 percent in August 2022. The index fell steadily to 47.3 in July 2022, suggesting the unemployment rate is set to rise further. This is the lowest value the index has seen since August 2011: The unemployment rate was 8.1 percent a year later. The low level of the expectations index predicts a rise in unemployment.

Another way to get at this is to use data on what we have called the “fear of unemployment”. In Europe, consumers are asked monthly, “How do you expect the number of people unemployed in this country to change over the next 12 months?” Responses are used to create an index, which predicts the onset of a recession extremely well. Blanchflower and Bryson (2022a)3 have adopted a plus-10-points rule when this fear-of-unemployment series rises 10 points in a 12-month period. This variable suggests the date of the start of the Great Recession as June 2008 in the UK, October 2007 in France and August 2007 in Germany.

In the US, the Sahm Rule has been suggested as a way of dating recession starts (Blanchflower and Bryson, 2022a)3. It identifies signals related to the start of a recession when the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate (U3) rises by 0.50 percentage points or more relative to the three-month moving average low during the previous 12 months. But rises in the unemployment rate in many countries don’t occur until after the final revised drop in output. Blanchflower and Bryson have shown that the Sahm Rule doesn’t work well in any other country except Canada. It dates the start of the recession in the US as February 2008, Canada and the UK as August 2008 and France as December 2008. In Germany, it predicts the start of the recession as April 2009, likely as a result of measures put in place by its government to lessen the impacts of slowing demand.

It seems to us that the US is currently in a recession based on the collapsed consumer confidence measures. Also of note is that US GDP figures for Q1 and Q2 of 2022 were both negative; based on the NBER’s prior three calls, this is also likely to be called as a recession, especially if there are downward revisions, which seem likely. We fully expect output to be negative in Q32022 as well. The euro area and the UK are probably also in recessions. China currently has the slowest growth rate in 40 years. Oil and other commodity prices are tumbling, and the costs of shipping goods have also slowed globally. A new survey from Grant Thornton reveals a sharp and continual decline in the optimism of chief financial officers (CFOs). In September 2021, 69 percent of CFOs had a positive outlook regarding the US economy over the next six months. In September 2022, that figure stood at 39 percent.

In 2022, consumer confidence has collapsed not only in the United States but around the world. In the UK, for example, the GfK consumer confidence measure is at its lowest point since the survey started in 1974. Similarly, consumer confidence in the eurozone has crumbled. These economies now appear to be in recessions. The World Bank is warning of a global recession (Guénette, Kose and Sugawara, 2022)4.

Raising interest rates in a recession is a bad idea. Inflation hurts, but a recession hurts much more. A new paper by Lina El-Jahel et al. (2022)5 has shown that a one-percentage-point rise in the unemployment rate increases pain 10 times more than a one-percentage-point rise in inflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) was 5.6 percent in July 2008 and -2.1 percent a year later. The unemployment rate in the US was 5.9 percent in July 2008, at the start of the Great Recession. It didn’t return to that level until September 2014. The Federal Reserve has claimed it will produce a “soft-landing” without a big recession. The chances of that seem slim. In 2008, central bankers didn’t have the precedent of 2008, but this time around, they do. There has been no learning, and as a result, ordinary people will lose their jobs.

Recessions hurt.

References

1 Bank of England: “Inflation, Expectations and Monetary Policy,” speech given by Professor David G. Blanchflower at the Royal Society, Edinburgh, April 29, 2008.

2 National Institute Economic Review (NIER)/Cambridge University Press: “The Economics of Walking About and Predicting Unemployment in the USA,” David G. Blanchflower (Dartmouth and NBER) and Alex J. Bryson (University College London and IZA – Institute of Labor Economics), August 19, 2022, 1-24, (2022b).

3 National Institute Economic Review (NIER)/Cambridge University Press: “The Sahm Rule and Predicting the Great Recession Across OECD Countries,” David G. Blanchflower and Alex J. Bryson, March 14, 2022, 1–51, (2022a).

4 World Bank: “Is a Global Recession Imminent?”, Justin Damien Guénette, M. Ayhan Kose and Naotaka Sugawara, EFI Policy Note 4, September 2022.

5 Journal of Money, Credit and Banking (JMCB): “How Does Monetary Policy Affect Welfare? Some New Estimates Using Data on Life Evaluation and Emotional Well-Being,” Lina El-Jahel, Robert MacCulloch and Hamed Shafiee, forthcoming2022.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Alex Bryson is a Professor of Quantitative Social Science at University College London (UCL) Social Research Institute. His research focuses on labour economics. He is a Research Fellow at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research and the Institute of Labor Economics. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society.