Over his 54 years as a financial analyst, Richard X. Bove perfected the art of grabbing attention.

Through thousands of newspaper interviews, cable news appearances and radio segments, Mr. Bove turned what can be a dull, by-the-numbers career into a more showy one. Weighing in on the economy and the inner workings of Wall Street, he often bucked conventional wisdom and made enemies along the way. By his own recollection, he never turned down a media request; American Banker once called him “the country’s most quotable bank analyst.”

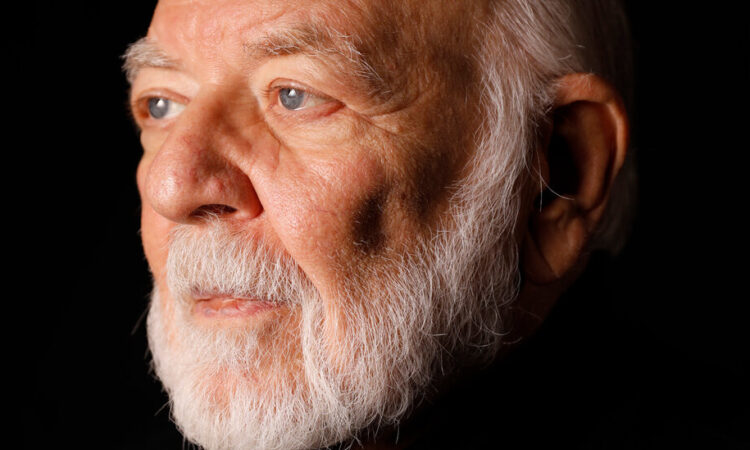

Last week, a few hours after completing a spot on Bloomberg television, the 83-year-old announced his retirement. He took that weekend off — and then jumped right back in. In an interview with The New York Times, Mr. Bove (pronounced “boe-VAY”), who goes by Dick, shared a dire outlook on the U.S. economy and his former profession.

“The dollar is finished as the world’s reserve currency,” Mr. Bove said matter-of-factly, perched in an armchair outside his home office just north of Tampa, from which he predicted that China will overtake the U.S. economy. No other analysts will say the same because they are, as he put it, “monks praying to money,” unwilling to speak out on the mainstream financial system that employs them.

Many analysts are rewarded for coming up with unique but inconsequential and “arcane” ideas, he said, peppering his criticism with profanities. Mr. Bove worked at 17 brokerage firms during his career.

As he spoke, a technician was trying to restore his home internet after his final employer, the boutique brokerage Odeon Capital, pulled the plug on his last day.

Mr. Bove, who began his career before A.T.M.s were commonplace, began appearing in the media in the late 1970s, when he was a construction industry analyst with pessimistic views on homes that didn’t always pan out.

He quickly shifted to weighing in on high finance, giving him a front-row seat to the savings and loan crisis that felled more than a thousand banks in the 1980s and 1990s. He later chronicled how the surviving banks bulked up with big bets that would lead to the 2008 financial crisis and a series of new regulations.

Among Mr. Bove’s more famous calls: identifying a “powder keg” in the housing market as early as 2005 (correct) and predicting that some major banks would quickly bounce back afterward (wrong). His 2013 book, “Guardians of Prosperity: Why America Needs Big Banks,” argued that crackdowns on the industry would crimp lending to small businesses.

He has now changed his tune on the primacy of U.S. banks, particularly after last spring’s regional banking crisis. He sees the offshoring of American manufacturing as the ultimate threat to the financial sector and the dollar, because “the people making the goods elsewhere are getting greater and greater control of the means of production and therefore greater and greater control of the world economy and therefore greater and greater control of money.”

Mr. Bove was fired twice from big firms, Dean Witter Reynolds and Raymond James, in the former instance for being too bullish on bank stocks. BankAtlantic, now defunct, unsuccessfully sued him over a critical 2008 research report.

The headline on a Times article about that episode called him “The Loneliest Analyst.” One way that’s still true is that he endorses cryptocurrency — an area that few other financial analysts will touch — which he sees as a natural beneficiary of the decline of the dollar.

Plenty on Wall Street viewed Mr. Bove as a crank or an attention seeker — but plenty of others listened. Those who paid attention included Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, whom Mr. Bove generally praises. Mr. Dimon, through a spokesman, said he had read Mr. Bove’s work to the end and found it “insightful.”

One who evidently isn’t a fan: Brian Moynihan, the head of Bank of America, who hasn’t spoken to the analyst in a decade, ever since Mr. Bove visited the bank’s Manhattan headquarters and told executives that they were foolish to expand their investment banking operation. (A spokesman for the bank said its head of investor relations didn’t recall the conversation.)

Mr. Bove now says he was wrong, and counts himself amused that he wasn’t invited back.

“I’ve liked to be a pain in the ass at times,” he said, pausing for effect. “A lot of the time.”

A Queens native who never quite shook his New York accent despite 30 years living in Florida, Mr. Bove attributes the longevity of his career to an independent streak that includes an unwillingness to read the work of any rival analyst. He readily admits that luck has played a part, too, marveling at his good health despite no regular exercise and a tendency to drink top-shelf tequila, neat.

He said he had earned more than $1 million one year but otherwise averaged $700,000 in annual pay. (Chief executives of major banks he covered can be paid more than $30 million a year.) That helped him buy a string of timeshares and invest in a handful of mostly unsuccessful business ventures, including four now-shuttered pizza parlors in the Tampa area.

Did he ever try his hand at making a pie?

“No, I never did,” he said. “That was the problem.”

Alain Delaquérière contributed research.