Can we really expect British banks to police rogue states? It’s unrealistic and an outsourcing of responsibility, says the City after claims Iran used four of the UK’s biggest lenders

Money, in the hands of rogue states and terrorists, is a deadly weapon. Banks and financial regulators go to enormous lengths to ensure that dirty cash is not sluicing around in their accounts and making its way to criminals or hostile nations.

So hearts sank across the City when allegations emerged that Iran has used three of the UK’s biggest high street banks as part of a vast plot to elude US sanctions.

The finger was also pointed at international bank Standard Chartered, which does not have branches here, but is headquartered in the City.

The allegations (see box below) were aired in the Financial Times and The Times. Each differs in detail. The common thread is that the banks actually did not provide services to sanctioned companies. The accusation is that the seemingly innocent firms in question were controlled by entities that were sanctioned – in particular by the state-controlled Iranian national oil company.

Their alleged true ownership was concealed through a chain of hidden and complex mechanisms. No one is happy at the thought of some of our most important lenders being used as stooges by Iran – least of all their chief executives who are horrified at the reports.

Iranian protesters burn a British flag during a demonstration against the US-led war, in Tehran in 2003

The allegations of Iranian sanctions evasion in the heart of the City came as the Royal Air Force joined US strikes against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen.

The immediate issue for the banks is whether they are culpable for their apparent failure to unmask some highly sophisticated and heavily disguised front companies.

The lenders are not helped by lax regulation that allows virtually anyone to set up a firm with minimal checks. Pariah states such as Iran, along with criminal gangs and fraudsters, are aware of this and they are able to exploit the system. There is little the banks can do.

The broader question is whether it is reasonable to expect banks to police the financial dealings of rogue nations.

One senior banking executive said: ‘Governments are outsourcing too much of their responsibilities for investigating hostile powers on to us.

‘But we don’t have access to the same information as the security services. It’s unrealistic. And at the same time we have to take care not to debank customers unfairly.’

The Iran reports could not have come at a worse time for the banks, the Government and the country. Lenders are only just emerging from the global financial crisis of 15 years ago and the consequences of the pandemic. The UK depends on a strong banking system to finance economic recovery.

The executive added: ‘There needs to be a serious conversation about these rules because if you want a strong economy, you need strong banks.’

A big scandal in an election year could hurt the Tories, who want to reprivatise NatWest in the biggest shareholder democracy drive since the 1980s. It could also fuel anti-capitalism more broadly.

The stakes are high. But no investigations are believed to be underway on either side of the Atlantic.

Lloyds has negligible business in the US – where the real threat of punishment lies. It is believed that no dollar transactions took place in the account in question.

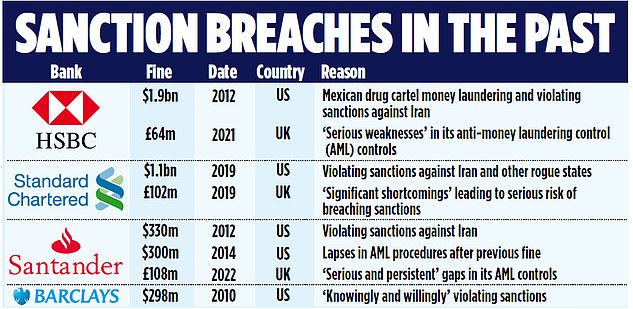

The US authorities have a history of imposing very heavy financial penalties when banks are found to have busted sanctions (see table).

There is also a history of UK companies and individuals being caught up in grandstanding by politicians and officials in the US. These include Eliot Spitzer, dubbed the Sheriff of Wall Street for taking on the banks when he was New York Attorney General between 1999 and 2006.

He went on to become New York Governor before resigning over links to a prostitution ring.

The Governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, and Chancellor Jeremy Hunt are concerned about the low level of valuations the stock market is putting on UK banks. Bailey last week described it as a ‘puzzle’ that they are valued so poorly, despite being much safer investments than before the financial crisis.

Hunt has even summoned bank bosses to Number 11 to inquire why they are so lowly valued compared with global rivals.

Bank shares have been doing badly even though their profits have had a huge boost as they cashed in on higher interest rates.

Reforms to boost the City have also had little impact on their share prices.

Over the past year, Lloyds is down 18 per cent, Barclays has dropped 16 per cent, NatWest is 25 per cent lower and Standard Chartered has lost 22 per cent.

Spanish-headquartered Santander and international giant HSBC are broadly flat.

Some diehard Remainers blame Brexit, but senior bank insiders say investors are put off by so-called ‘conduct risk’ – in other words the fear that lenders may be hit with huge fines and damage to their reputations regardless of whether they deserve it.

This worry is not confined to lurid allegations about terrorism and renegade nations, but more mundane issues such as the potential mis-selling of car loans, which has resulted in hundreds of millions of pounds being wiped off the value of one of Britain’s oldest banks, Close Brothers.

Banking insiders suggest that car finance – which consumer champion Martin Lewis has said could be similar in scale to the PPI scandal – could prove a bigger problem than Iran, which many believe to be a storm in a teacup.

One reason the UK financial system is vulnerable to being infiltrated by pariah states, terrorists and criminals is the ease with which it is possible to set up a ‘shell’ company. So-called shells can be useful vehicles for bad actors. Shell companies usually have financial assets and hold funds, but do not trade and have no employees.

Registering a shell UK company takes little time and costs £12. Almost anyone can own and manage a limited company as long as someone aged over 16 is listed as a director and their address is not a box number.

The Treasury is looking at the role of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) – the City watchdog which is responsible for policing money laundering and terrorist financing

Anyone from anywhere in the world can set up a company in the UK. Companies House, where all firms must be registered, does not verify names and addresses.

MPs this month asked the Government to set out how it is tackling the use of UK-registered companies by Iran and other states, which exploit the laxity of our system to circumvent sanctions.

Liam Byrne, who chairs the all-party Business and Trade Select Committee, wants Ministers to publish an estimate of the scale of the problem.

A recent report from data research agency Moody’s Analytics found that UK shell companies triggered almost 5 million ‘red flag’ alerts that they may be being used as funnels for dirty money. This is more than any other country.

In the most extreme case, one individual had 5,751 roles at 2,883 different companies, while another firm had 292 directors.

‘We want to be open to business, but we are also open to abuse,’ said Ted Datta, head of financial compliance at Moody’s. ‘Like any system there are bad actors.’

The UK has also faced criticism for failing to target financial criminals, bringing just 23 cases against bankers and financial insiders for failing to report money laundering suspicions between 2012 and 2021.

Companies House is currently implementing a new identity verification process.

Banking expert Philip Augur believes there is a two-speed system at work.

He said: ‘I have always been struck by the anti-money laundering bureaucracy faced by people wishing to, for example, become a new client of a bank and the apparent ease with which large corporations and high net worth individuals are able to glide round sanctions.’

So what can be done?

The Treasury is looking at the role of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) – the City watchdog which is responsible for policing money laundering and terrorist financing.

It is a role the FCA undertakes along with a patchwork of other bodies, but an entirely new organisation may be formed to cover end-to-end transactions. A decision is due in the summer.

In the meantime, experts say the banks need to dig much deeper to unearth what really lies behind shell companies.

‘They need to go beyond “the list’’ on sanctions evasion given the heightened geopolitical risk landscape and their continued exposure to Iran via proxy companies,’ said Moody’s Ted Datta.

But there are limits to how far they can reasonably go. Datta said: ‘It’s a tough ask for banks.’

How Brexit helps clean up dirty cash

The Mail on Sunday has led the way in highlighting how the European Union has pandered to financial crime since Brexit.

A controversial ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in 2022 decreed that an individual’s right to privacy trumped the public’s right to know who owns a business.

But the British Government believes access to ownership documents helps in the fight against dirty money and hostile powers.

And the UK was able to ignore the ruling because we are no longer obliged to go along with ECJ decisions following Brexit.

The Mail on Sunday unmasked the shadowy Luxembourg-based businessman who brought the initially successful case to the ECJ to protect the interests of secretive corporations and their owners.

Patrick Hansen runs a private jet firm which has counted wealthy Russians among its clients. Several of its planes were grounded after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine triggered sanctions against oligarchs.

The original ruling by the EU’s highest court played into the hands of sanctions-busters, kleptocrats and other tax evaders by limiting public scrutiny of who really controls companies.

This newspaper alerted the Department for Business to the controversial judgment.

Our warning prompted the Government to confirm the British public’s right to continued free access to ownership files at Companies House, which would have been under threat had we accepted the ECJ verdict.

Now, in a major climbdown, the EU has also allowed general access to ownership registers, including by journalists.

‘This will make it significantly harder for criminals to hide their ill-gotten gains,’ said Roland Papp of the Transparency International campaign group.

EU members, including Ireland and the Netherlands, rushed to limit access to ownership records after the ECJ ruling.

They are now under growing pressure to open up their files again.

‘It is now critical that member states implement these rules without delay,’ Papp added.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.