European leaders have become so annoyed with the Hungarian government’s obstruction over aid to Ukraine that they are exploring how to wage financial warfare against a fellow EU member state. Their frustration is understandable. But do they actually have the ability to inflict the kind of pain they want?

By most measures, Hungary is a hard target. Moreover, the ideas being reported in the public domain are unlikely to squeeze the Orbán regime hard enough—or fast enough—to be helpful. However, some vulnerabilities in the Hungarian financial system have recently emerged that could potentially be exploited by creative policymakers.

This is how the Financial Times describes the Europeans’ plan:

In a document drawn up by EU officials and seen by the Financial Times, Brussels has outlined a strategy to explicitly target Hungary’s economic weaknesses, imperil its currency and drive a collapse in investor confidence…The document declares that “in the case of no agreement in the February 1 [summit], other heads of state and government would publicly declare that in the light of the unconstructive behaviour of the Hungarian PM . . . they cannot imagine that” EU funds would be provided to Budapest. Without that funding, “financial markets and European and international companies might be less interested to invest in Hungary”, the document stated. Such punishment “could quickly trigger a further increase of the cost of funding of the public deficit and a drop in the currency”.

As stated, this will not work. EU funds have historically been worth about 2% of Hungary’s economic output each year. That has been helpful for Hungarians, as well as to Orbán, who has used the money to reward cronies. But losing access to those funds is not going to break the Hungarian economy. After all, Hungary has already been cut off from much of the EU funds for which it is theoretically eligible due to concerns about Orbán’s corruption and abuse of power.

More generally, the Hungarian economy and financial system were transformed after the global financial crisis in ways that make them much less vulnerable to external pressure. Some Europeans may feel nostalgiac for the bloodless coup in Italy that replaced Silvio Berlusconi with Mario Monti, but Orbán is aware of the precedent and long ago made sure that he will not meet the same fate. Like the Soviet Union under Stalin (who saw what had happened to Britain, France, and Germany after WWI), China under the CCP (who saw what had happened to Suharto in 1998), or Russia under Putin, Orbán knows that orthodox macroeconomic policy and financial self-insurance are some of the best defenses against foreign interference.

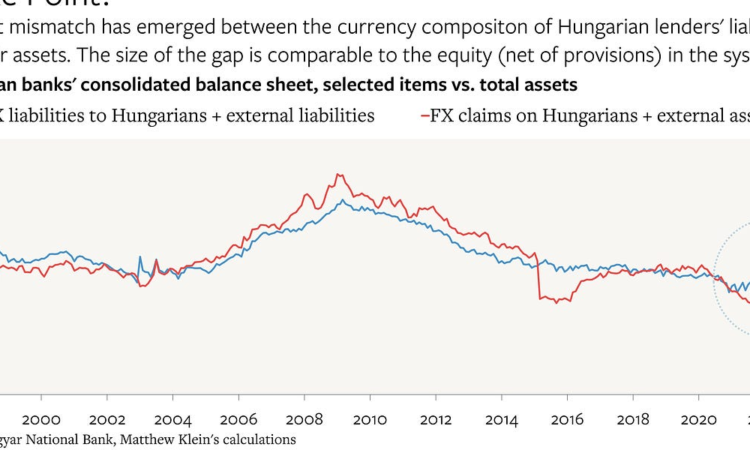

Hungary had a mortgage bubble in the 2000s, with many mortgages denominated in euros and Swiss francs that were in turn financed by borrowing from abroad. That ended badly, and like many other European crisis countries, Hungarian import volumes fell sharply and stayed low for years—the 2008 peak was not surpassed until 2014—while exports fell somewhat less and recovered slightly faster. Another way of saying the same thing: actual individual consuption stagnated for a decade even as overall GDP rose.

The result is that—with the notable exception of the 2022 energy shock—Hungary has had a persistently large current account surplus ever since the 2008 financial crisis.