By David Milliken and William Schomberg

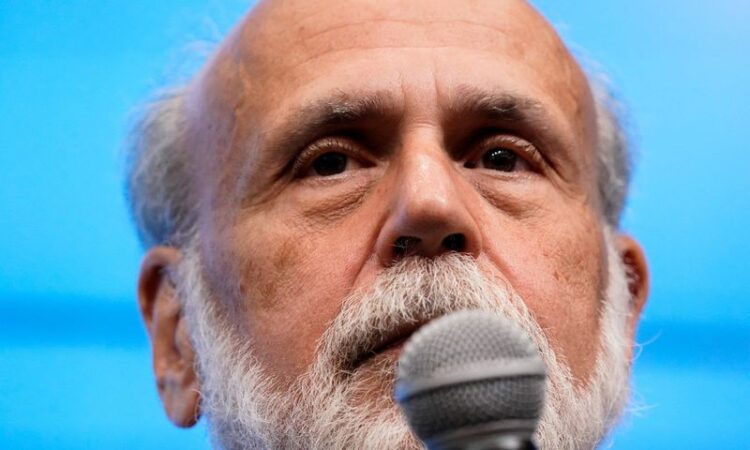

LONDON (Reuters) -The Bank of England should scrap communication tools that it has used for a generation and upgrade “seriously out of date” technology to overhaul its approach to economic forecasting, former U.S. Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke said.

After a surge in inflation to a 41-year high in 2022 which turned a spotlight on the BoE’s inner workings, Bernanke released a report on Friday which advised the UK’s central bank to publish more alternative scenarios for the economy.

The Nobel prize-winning economist proposed that the BoE should rely less on market expectations of interest rate moves, among other measures to improve its forecasting.

But he stopped short of recommending that the BoE publish its own forecast for where interest rates might head, saying this more radical option should be left for discussion.

“While the accuracy of the BoE’s forecasts has deteriorated significantly in the past few years, forecasting performance has worsened to a comparable degree in other central banks and among other UK forecasters,” Bernanke concluded in the report, which was commissioned by the BoE’s oversight body last year.

British consumer price inflation surged above 11% in October 2022 after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused a surge in European gas prices, compounding post-pandemic bottlenecks.

Some politicians and economists criticised the BoE for only starting to raise interest rates in December 2021, when inflation was already above target. The BoE has said an earlier start would have made little difference.

Bernanke described the BoE’s failure to foresee the inflation surge as “probably inevitable” due to “unique circumstances”.

The biggest failure was in the BoE’s forecasting systems which had “significant shortcomings” that made it hard for staff to produce alternative economic scenarios and needed “replacing, or, at a minimum, thoroughly revamping”.

Bernanke said the BoE should eliminate its long-standing “fan chart”, which shows a range of possible future paths for inflation and growth based on a single set of assumptions.

Instead, the BoE should give a more descriptive assessment of risks and publish alternative scenarios that show how the BoE might change interest rates if the economy did not develop as expected, and what impact these changes would have.

Governor Andrew Bailey said work was underway to improve the BoE’s data platforms over the next year or so and policymakers would set out further steps on communication by the end of 2024.

“The Bernanke Review won’t be a game-changer for how policy is conducted,” Deutsche Bank chief UK economist Sanjay Raja said. “Any external changes will be gradual, with bigger changes likely to take place behind the scenes.”

NO ‘DOT PLOT’

Bernanke, who headed the Fed from 2006 to 2014, did not recommend that the BoE move closer to the U.S. central bank’s “dot plot”, where each rate-setter anonymously publishes their own forecasts for interest rates, growth and inflation.

The BoE, unlike the Fed and the Swedish and Norwegian central banks, does not publish its own interest rate forecasts.

Bernanke said there was a case for this “more aggressive approach” but it would be “highly consequential” and should be left for future debate.

If the BoE did go down this route, it should produce a single rate projection, as Scandinavian banks do, rather than a Fed dot plot with individual policymaker views, he said.

Some senior BoE officials have previously opposed rate forecasts, worrying they would be misinterpreted as a commitment rather than a best guess which was likely to change.

Bernanke said this had not been his experience at the Fed, or a major problem for Sweden or Norway, though it did sometimes put pressure on policymakers in times of uncertainty.

“The problem with rate projections is they force you to take a stand when perhaps you don’t feel it is really appropriate,” he told reporters.

The BoE currently produces two sets of projections for inflation, growth and unemployment. One is based on interest rates staying unchanged, and the other on what financial markets think will happen to borrowing costs over the next three years – similar to the European Central Bank’s approach.

Investors often look at the BoE’s forecast for inflation two years ahead to get a sense of whether the central bank thinks the market path for interest rates is too high or too low.

Some former officials have said this can lock the central bank into making forecasts based on interest rate assumptions that policymakers sometimes themselves do not believe.

Bernanke said the BoE should reduce the emphasis on forecasts based on market rate assumptions and be “exceptionally clear” when policymakers disagreed with them.

Alternative scenarios, or explicit changes to the assumptions, could be a way to do this.

(Reporting by David Milliken and William Schomberg; Editing by Catherine Evans)