One September morning three years ago, the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations grilled Julie Chung, a deputy assistant secretary for Western Hemisphere affairs in the State Department, about what the Trump administration was doing to counter China’s rising influence in the Americas. To defend the administration, Chung mentioned an obscure regional development bank, the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI), to which the United States had pledged financing. The administration worked “in partnership” with Taiwan at the bank, she emphasized, without specifying how: “Taiwan and the United States are working together in Latin America.”

Two years later, in March 2022, Andrew Herscowitz, an executive at the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, told the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee on Western Hemisphere issues that the United States, now under President Joe Biden, had recently loaned $100 million to CABEI, and that the investment helped one-up China. Washington’s disbursements to the bank “advance U.S. foreign policy objectives,” he said.

The officials described CABEI through a U.S. lens, but the bank is an intrinsically Central American institution. It is jointly run and partially funded by a group of governments in the region, five of which—Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Costa Rica—created it in 1960 in the name of integration and reclaiming sovereignty. Those countries aimed to escape the shadow of superpowers and fund their own growth by pooling money to lend to each other. CABEI’s membership and financing capacity expanded over time, as it accrued public and private backing from the United States as well as Europe and Asia. Between 2000 and 2018, the bank approved loans totaling about $30 billion.

But in the past decade, CABEI has faced mounting criticism in both Washington and Central America. Environmentalists such as Berta Cáceres said the bank funded infrastructure projects that violated Indigenous rights and fomented violence. (Cáceres was murdered in Honduras in 2016.) Democracy watchdogs tracked member governments lending themselves money as they fell to autocrats, such as Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega and Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, who then propped themselves up on the largesse of CABEI.

Last year, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which partners with global media on cross-border investigations, obtained a trove of internal bank documents. The organization probed deeper, conducting interviews with a multitude of activists and experts who include current and former CABEI executives. The reporters submitted Freedom of Information Act requests and scraped the bank’s webpage, working with 11 Central American, U.S., and Asian outlets to report on the ground. I joined the effort early this year in El Salvador and Honduras as an independent journalist.

OCCRP and its media partners began publishing the investigation in late October, exposing a slate of problems in the bank. Above all, the journalists found, CABEI has become an easy source of cash for regional authoritarians; they labeled it with the colloquial moniker “the dictators’ bank.”

The journalists’ evidence also revealed financial mismanagement and little oversight over how countries spend CABEI funds. Reporters reviewed internal audits that showed the bank ignored red flags when investing in projects, and that its loans had been used to pay bribes and buy votes. Some members of CABEI’s leadership sounded an alarm in 2021, when they wrote an internal letter warning of the bank’s deteriorating financial health and poor transparency practices. El Salvador—whose government took CABEI money earmarked for pandemic relief and spent it instead on making bitcoin a national currency—exemplifies the bank’s issues.

When presented with OCCRP’s revelations, outgoing CABEI President Dante Mossi defended his leadership and the bank. “CABEI is not a political institution,” he told reporters. “We do not have the mandate to determine the form of government of any member country,” he said, adding that the bank’s finances are “better than ever” and denying that its practices make its funding prone to corruption. (Mossi’s successor, a Costa Rican industrial engineer named Gisela Sánchez, was elected on Nov. 17 and will begin her five-year term on Dec. 1.)

What the investigation revealed has serious implications for CABEI—but it also begs reflection from Washington, which has used the bank as a tool of statecraft for decades.

- Demonstrators protest outside the Central American Financial Integration Bank in Tegucigalpa on April 1, 2016, after the murder of Indigenous activist leader Berta Cáceres. Orlando Sierra/AFP via Getty Images

- A resident of Honduras demonstrates in front of the U.S. Embassy in Tegucigalpa, demanding that the U.S. government not support the El Tigre dam project. Hundreds of Hondurans also protested in front of the headquarters of the Central American Bank for Economic Integration. Elmer Martinez/AFP via Getty Images

It’s difficult to determine the total amount of money that the U.S. government has invested in CABEI over the years. But in leafing through federal reports, it is clear that the United States has engaged with CABEI since the bank’s founding, and that by the late 1980s, Washington had invested millions in it.

In 1984, a congressional commission chaired by former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger recommended—unsuccessfully—that the United States become a CABEI member. This would have entailed a more significant financial commitment on Washington’s part—making it a shareholder so that, in the commission’s vision, the funds would fortify the bank’s power to reinvigorate the Central American private sector, a perpetual U.S. foreign-policy goal.

In 2004, the bank’s chief economist suggested the same, citing potential financial benefit to CABEI, to no avail. Three years later, the bank’s president, who is its administrative authority and legal representative, again petitioned the United States to join—this time because, he claimed, internal CABEI sympathies were tipping toward Venezuela, an antagonist of Washington.

But the United States never joined CABEI. Instead, for half a century, it has seen the bank as a small geopolitical chessboard. Washington doesn’t play directly but it helps fund the game through means such as loaning CABEI money as humanitarian and development relief; connecting the bank with the U.S. private sector; and partnering with the bank to cost-share aid works, including housing and highways.

Some in Washington increasingly believe that game is about thwarting Beijing. They point to China’s growing presence in Central America. Once home to many Taiwan-friendly governments, the majority of the region’s administrations now recognize Beijing over Taipei; only Belize and Guatemala retain diplomatic relations with the latter. Most Central American countries have, or are negotiating, free trade agreements with China, and most have joined its Belt and Road Initiative.

Beginning in the early 1990s, CABEI inducted 10 additional members whose economies largely dwarfed those of the five founders. Taiwan, South Korea, Spain, and Mexico were among the new shareholders that made millions of dollars in capital contributions, boosting the bank’s credit rating and thereby ensuring it access to cheaper money when it sought outside financing.

Like the United States, China has never been a CABEI member—but Taiwan is crucial to the bank, turning it into a venue for proxy competition between Washington and Beijing. The island’s decision to join in 1992 enabled CABEI to issue its first bonds on the international market, and Taipei now holds nearly 11 percent of the bank’s shares. (In response to the OCCRP investigation, Taiwan’s Finance Ministry issued a statement calling for reforms to CABEI.)

In March 2020, CABEI was set to hold an internal referendum on whether to establish an office in Taiwan. (The bank has offices in two-thirds of its member countries, mostly in Central America.) The Costa Rican representative to the bank, economist Ottón Solís, opposed the initiative. He told me that it would be expensive and unnecessary; in his words, CABEI was already throwing money around “as if it were a Saudi Arabian petro bank.”

Solís received an email from the U.S. State Department that lobbied him to vote for opening the office. The email argued that the bank had issued more than a fifth of its debt—nearly $2.3 billion—on the Taiwan capital market. The State Department’s message complained that the People’s Republic of China was trying to sway countries to vote against the office. “Taiwan is a reliable partner, a democratic success story, and a force for good in our hemisphere,” the email read, continuing: “The United States stands in firm opposition to the PRC’s bullying tactics.”

The vote was ultimately successful. As Taiwan lost diplomatic ground elsewhere, it solidified its foothold in CABEI—just as the United States had hoped. The State Department did not return a request for comment.

For many bank insiders, Solís among them, CABEI reinforces the sovereignty of Central American countries. He believes the United States should not join the bank because CABEI is one of the few financiers available to the region whose money is not conditioned by U.S. economic and political ideology. Solís thus sees lobbying by hegemons, whether the United States or China, as undue intervention.

But Solís and many of his colleagues are also worried about CABEI’s weaknesses.

A man walks past a wall painted with an anti-bitcoin symbol in San Salvador on Oct. 18, 2022. Marvin Recinos/AFP via Getty Images

One country in particular—El Salvador—exemplifies what happens when CABEI’s problems meet a contest between superpowers. There, the bank is helping to fund democracy’s demise.

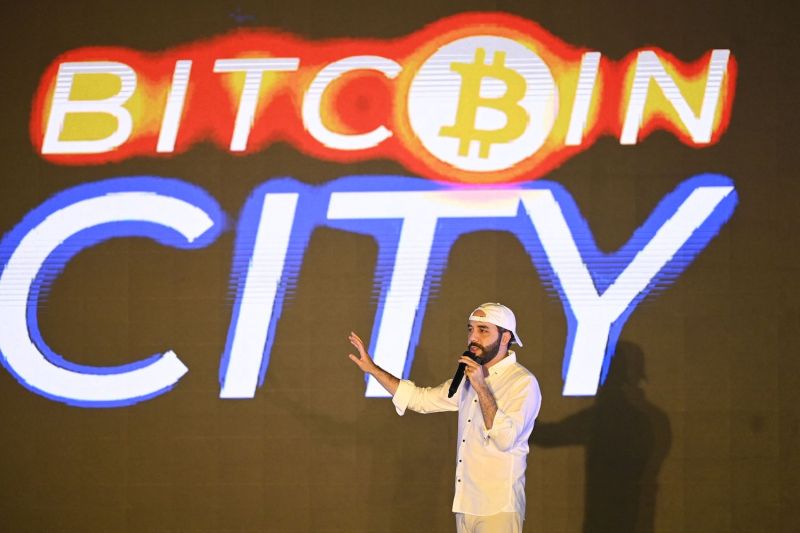

In April 2021, CABEI lent $600 million dollars to El Salvador to fund a COVID-19 relief program for small- and medium-sized businesses. It was then the largest loan in the bank’s history. But the Salvadoran Congress, controlled by Bukele’s party, instead voted to divert one-third of the $600 million to the president’s vanity project: making bitcoin a national currency.

The legislature sent $160 million to a state bank, BANDESAL, to form a national bitcoin trust, which would reimburse Salvadoran companies receiving payment in bitcoin with dollars—the country’s other official currency. The Congress then destined $23 million for “the implementation of the bitcoin law” and gifted a total of $30 million to 1 million Salvadorans—$30-worth of bitcoin each—delivered via the government’s digital wallet app and meant to incentivize a widespread leap to crypto in a country that was skeptical of it. (The ploy failed.) The Salvadoran legislature scattered the remaining $400 million that didn’t go to bitcoin among a few government ministries; only about $20 million ended up helping entrepreneurs recover from the pandemic.

El Salvador appears to have faced no consequences from CABEI. Mossi told OCCRP that CABEI money wasn’t supposed to be spent on bitcoin-related purposes, but that “the government can use the money as they wish.” The Salvadoran government did not respond to a request for comment.

Economist César Villalona said the CABEI-funded bitcoin installation remains unpopular among Salvadorans and “stoked concerns of corruption and money laundering.” The administration has kept most details about how crypto circulates in the country secret. This includes exactly how much public money Bukele has gambled away by buying bitcoin.

The likelihood that CABEI would demand accountability from El Salvador is low. That’s because of the design of the bank, former Director of the Salvadoran Central Bank Carlos Acevedo told me: CABEI is run by a board of directors composed of political appointees from each member government. This renders the leadership little more than “a club of friends” who perfunctorily rubber-stamp each other’s requests, which Acevedo called “influence trafficking.”

Bukele’s affinity for CABEI became clear in February 2020, when he invaded the Salvadoran Congress with the military to try to force a vote on whether to accept a CABEI loan meant for the police and army. Once inside, Bukele sat in the chair belonging to the congressional president and prayed, surrounded by camouflaged men with rifles—a quintessential snapshot of a dictator. His coercion to vote was unsuccessful, but Bukele’s party swept the subsequent legislative elections, winning a supermajority. Several months later, Congress voted to approve the loan.

Before long, Bukele had deconstructed El Salvador’s justice system to make it friendly to him—overhauling the Supreme Court and the attorney general’s office and forcing the retirement of one-third of the country’s judges. A growing cohort of Salvadoran jurists, journalists, and democracy and human rights activists have been forced into exile.

In late October, Bukele violated the constitution by launching his candidacy for a second consecutive term as president; while the judges that Bukele placed on the Supreme Court invented a legal carve-out that they say renders his reelection legal, most experts disagree.

- Gerson Snayder, a former Nicaraguan political prisoner who now lives in exile in Costa Rica, chains himself to the entrance of the Central American Bank for Economic Integration building to protest against the loan that CABEI would deliver to the Nicaraguan government in San Jose, on Feb. 28. Ezequiel Becerra/AFP via Getty Images

- Nicaraguan citizens exiled in Costa Rica demonstrate in front of the CABEI building in San Jose on Nov. 19, 2021, to demand that the bank stop providing loans to the Nicaraguan government. Ezequiel Becerra/AFP via Getty Images

At first, the Biden administration reacted to Bukele’s autocratic moves with blunt condemnation—though, for unclear reasons, Washington has since softened. In 2021, the administration named the five Bukele-appointed Supreme Court judges to its Engel List, which denounces “anti-democratic and corrupt” actors in Central America. The U.S. chargé d’affaires in San Salvador, Jean Manes, went on a popular Salvadoran morning show and, visibly angry, accused the justices of making undemocratic decisions such as “allowing the reelection of their president, which is clearly not allowed by their constitution.” But by October 2023, the Biden administration was blandly calling Bukele’s reelection a subject of “debate.”

Some bankers retreated. In mid-2021, global credit rating agencies were warning about the democratic decline, and the Bukele administration began hitting barriers from financial markets and the International Monetary Fund. In November 2022, when more than $600 million in bond payments were nearly due, Salvadoran Vice President Félix Ulloa told Bloomberg that China had offered to buy the country’s debt. He said the administration would “tread carefully” and was considering the sale.

Then China denied having made the offer, and Salvadoran officials began claiming—unconvincingly—that Ulloa’s quote was taken out of context.

It seemed clear to analysts that Ulloa’s statement was a stunt meant to warn the United States, traditional financiers, or both that if they didn’t cough up the cash, El Salvador would get it elsewhere. It didn’t sway them—but it did move CABEI, which channeled a $450 million loan to the Bukele administration to spend on buying back its own debt. (A portion of the loan had been previously approved, but more than half of it was first announced days after Ulloa’s comments.)

The buyback improved El Salvador’s bond performance, but that ultimately doesn’t mean much, Salvadoran economist Tatiana Marroquín told me. “Yes, there was now a ‘someone’ who wanted to buy them [the bonds], but that was the state of El Salvador. And in a dynamic of supply and demand, that makes the price go up … but that is not actually an indicator of an improvement in Salvadoran public finances,” she said. “The reality is that El Salvador is in serious trouble.”

A man wearing a cloth face mask with the image of Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s face on it poses for a photo at a bitcoin ATM in San Salvador on Sept. 7, 2021. Marvin Recinos/AFP via Getty Images

Nevertheless, when Bloomberg reported on the bond rally in September, Bukele retweeted the article along with the message, “I will not say ‘I told you so,’” in English, along with a cry-laugh emoji.

CABEI had already been extraordinarily generous to Bukele: In 2021, the country that received the most money from the bank, more than $1 billion, was El Salvador. That was more than twice the amount awarded to the next-highest recipient, Nicaragua—a country also run by an authoritarian leader.

The bank’s money and legitimacy come from its backers, including the United States—which has one eye eastward. “China and the United States have the same objectives. Both are imperialists,” Marroquín said. “What they’re fighting over is who will be considered the ambassador,” she said—the top diplomat in San Salvador.

China’s growing interests in Latin America are about economics and, according to Ana María Méndez Dardón, the director for Central America at the Washington Office on Latin America, it’s probable that one reason that the Biden administration has gone mum on Bukele is the fear that he will give Beijing what it wants. “Bukele has made threats in public, and the U.S. is scared that El Salvador and the other countries of the region could build stronger ties with China,” she said.

New to the statesmanship game, the Salvadoran president is pinballing off the insecurities of superpowers and knocking loose what he can. In March 2023, two U.S. congressional committees, Senate Foreign Relations and House Foreign Affairs, asked CABEI’s members in an open letter to stop funding the dictatorship in Nicaragua.

The letter said nothing about El Salvador.