The British hawks have descended. Last Thursday came news that caught U.K. markets off-guard and surprised even seasoned observers of the curious overlap between politics and monetary policy: The Bank of England will raise interest rates by 50 basis points.

The bank’s inflation target is 2%, while actual inflation is currently at 8.7%. On Wednesday, the Monetary Policy Committee voted to hike rates for the 13th consecutive time, with seven in favor of a 50 bps raise and two voting for no raise. But where there was some agreement at that table, outside the BoE there was rancor at its continued pursuit of a strategy that for the most part does not appear to be working.

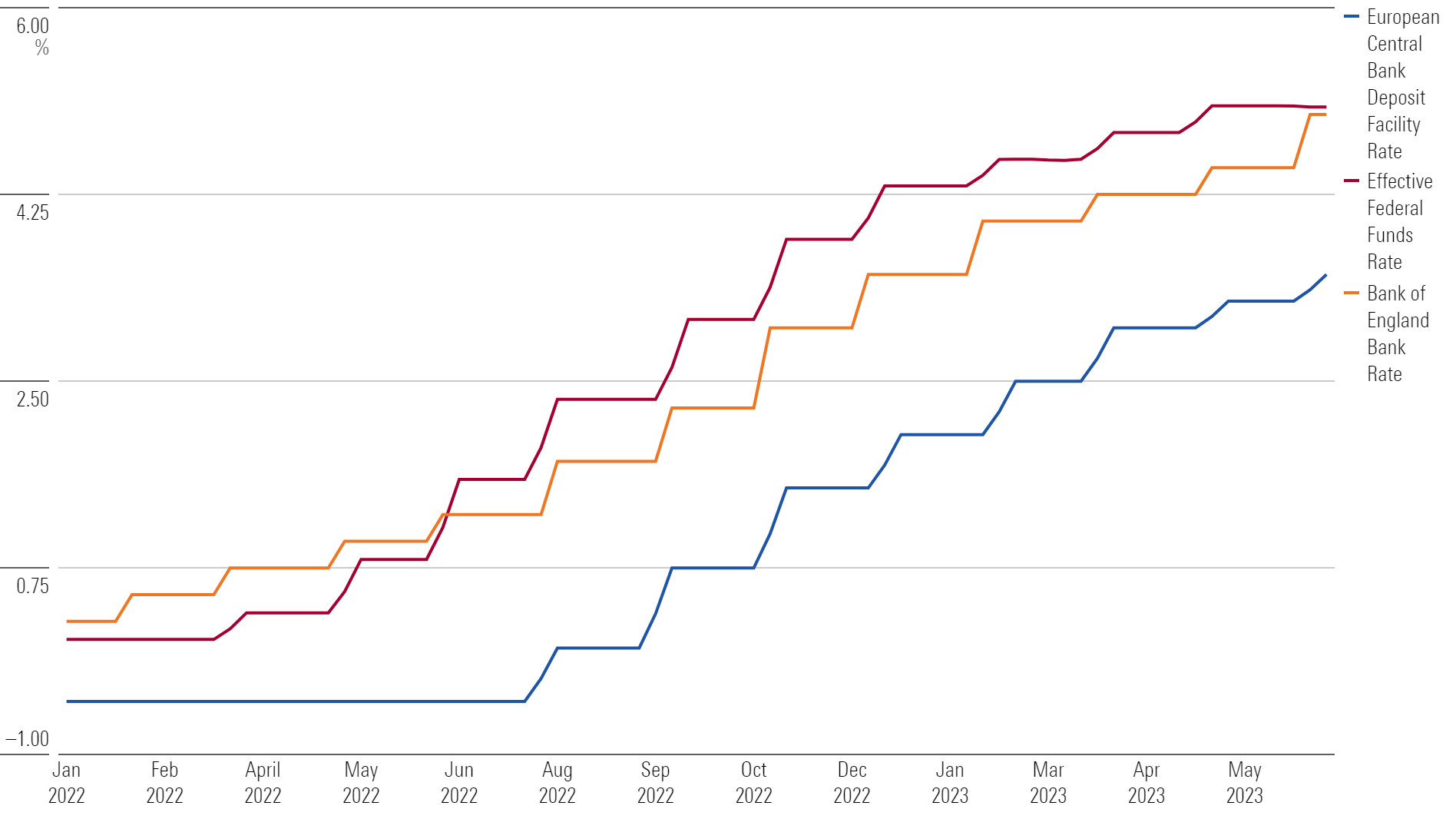

Meanwhile, Europe also continues its battle with price rises. In contrast to a recent downward trend, Germany’s inflation rose at a stronger-than-expected pace of 6.8% in June. Earlier in the month, the European Central Bank raised its key rate by a quarter of a point to 3.5%. The ECB’s deposit facility rate stood at 2% at the end of 2022 and was at zero last July.

In fact, ECB President Christine Lagarde has signaled more rate rises are on the way, including at its July policy-setting meeting. “It is unlikely that in the near future, the central bank will be able to state with full confidence that the peak rates have been reached,” she said last week.

Why Isn’t U.K. Inflation Slowing?

Observers may wonder why U.S. rate hikes have begun to tame inflation, while progress (if it can even be called that) is so much slower in the United Kingdom and Europe. The short answer is that the United States is to a degree less economically vulnerable. Supply chain constraints have eased in the country, and rate hikes are working. But other events have also benefited the Federal Reserve’s efforts.

In May, Fed Chair Jerome Powell admitted that the demises of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank led to a tightening in credit markets, negating the need for further hikes. This may seem a bizarre turn, given the vulnerability caused by a banking crisis, but it’s a case study of something being bad for one group and good for another. Some commentators now feel comfortable arguing the Fed can win its inflation fight without even tipping the U.S. into recession.

In the U.K., the narrative is suddenly very different. While before people speculated about the “risk” of a recession, there is now a sense it may be the only answer to sky-high inflation. As policymakers grapple with the knock-on effects of higher rates on the cost of U.K. debt (and, worryingly, mortgages), they are painfully aware that going too far could preclude people from paying down capital in the first place.

According to the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority, the outstanding value of all residential mortgage loans was GBP 1.7 trillion at the end of the first quarter of 2023—2.7% higher than a year earlier, but a decrease from the previous quarter for the first time since the second quarter of 2017.

The government is now intervening. Last week, meetings between Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt and major retail banks produced a swift outcome: clemency for homeowners at risk of repossession and interest-only switches for those struggling to make payments in the short term. Also encouraging is that more people in the U.K. now own their own homes outright than have a mortgage or rent. But that’s not enough to start celebrating; housing is still the U.K.’s biggest economic vulnerability.

Who’s to Blame?

Monetary orthodoxy would have investors believe rate rises are the key to conquering inflation because they dampen demand. On the one hand, people supposedly get more bang for their buck from their accounts because the rewards for saving are greater. On the other hand, they will pay more on their debt. That means less is spent, for good or ill.

Britain has enough of a savings culture for struggling families to notice the first part. And that’s without banks’ failure to properly pass rate rises on to customers. And people may well instinctively want to tighten their belts, but in some cases they already were. And where they can’t afford the basics, credit cards or loans will do the heavy lifting. Rising interest rates will hammer such people twice.

At the start of the U.K.’s cost of living crisis, the price of energy was constantly making the headlines. As summer temperatures rise, those headlines have gone quiet. Today it is the burdensome cost of food that causes concerns.

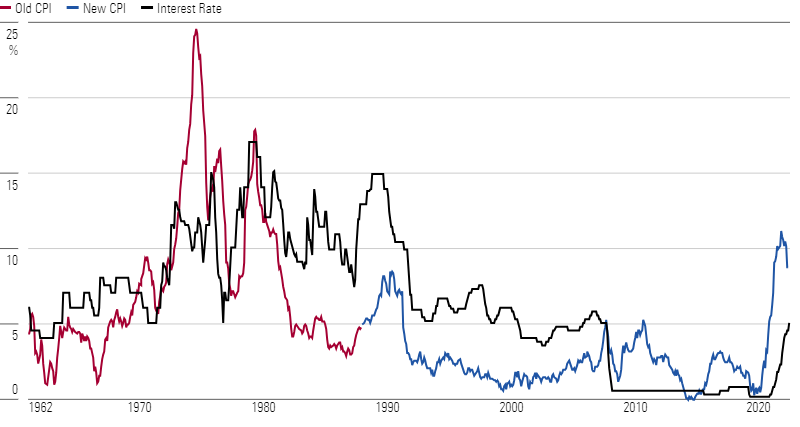

According to the Office for National Statistics, “the annual inflation rates for food in March and April [2023] were the highest seen in over 45 years.” Food prices have trended slightly downward since, but they are still stubbornly high. Everyone sees that when they go to the supermarket.

At the moment, the BoE is taking the flack. When the bank’s governor Andrew Bailey insisted in February 2022 that people shouldn’t ask for pay raises, he was accused of being out of touch.

What’s more, the BoE’s inflation modeling has been disastrously inaccurate. And Bailey’s record as former chief executive at the FCA hasn’t helped; a string of scandals there under his watch led MPs to ask whether his appointment to the Bank’s top job was even appropriate.

The hawks may have descended, then, but it’s not yet clear whether that will placate a prime minister desperate to halve inflation by the end of 2023, or voters facing another round at the ballot box in 2024. During May’s local elections, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s party was handed a drubbing.

For now, expectations are that the Bank of England’s rate increases will continue.