In the years that followed, tech giants including Facebook, now known as Meta, LinkedIn and Twitter all set up in Dublin’s redeveloped docklands.

More than 100,000 people are now employed by multinational technology companies in Ireland. Around 16pc of Ireland’s gross domestic product now rests on Big Tech’s revenues and taxes, meaning Silicon Valley is arguably more important to the country than Brussels.

There are fears the economic miracle of the “Celtic Tiger” could now be under threat.

One source close to Ireland’s tech sector says divergence from the bloc was “tolerated when Ireland was a poor country” but “once tech companies started to use Ireland, in Europe there was a perception of a ‘beggar thy neighbour’ effect.”

The rift spilled out into the open in the middle of the last decade after the European Commission sued Apple over its tax affairs in Ireland.

Ireland’s tax treatment of US multinationals has been particularly disliked. With a rate of 12.5pc, Dublin has one of Europe’s lowest corporation tax burdens.

iPhone giant Apple secured a bespoke deal on taxes that triggered a backlash from the European Commission. Brussels ordered the company to pay $13bn extra to Dublin in 2016, saying the tax breaks were unfair state aid that distorted the market.

The decision was overruled by a court in Luxembourg. An appeal is expected to be heard this year as the world’s biggest company and the world’s would-be biggest regulator duke it out, with Ireland caught between the two.

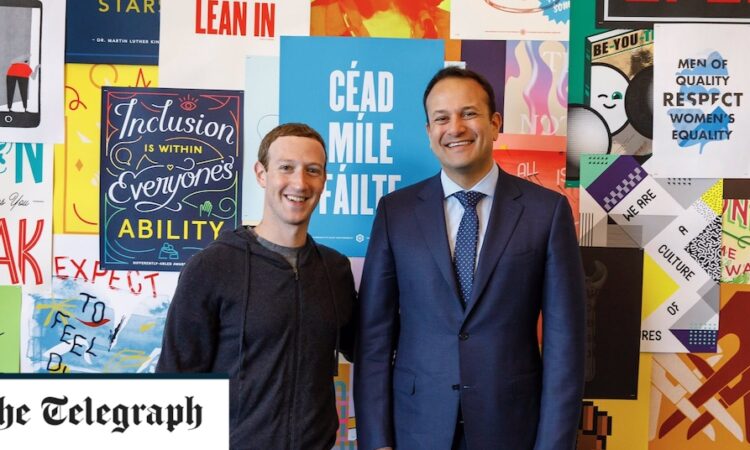

The latest split has emerged after an investigation into how Facebook’s parent company Meta handles data.

The Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) plans to take its EU counterpart to court over claims the bloc tried to pressure it into launching a wide ranging investigation into Facebook’s parent company Meta.

Privacy advocates have accused Ireland’s data regulator of going soft on tech companies.

Max Schrems, the Austrian campaigner who triggered the DPC’s investigation, alleges the Irish regulator “dragged out its decision for four years” and held up to 10 meetings with Facebook in order to “bypass” EU data laws.

Schrems points to documents revealing backroom rows between the two regulators over how to treat Meta after investigators concluded Facebook had broken EU data protection laws.