Government budgets across Europe are in shambles. They took a beating during the pandemic-related artificial economic shutdown, and they have not recovered since then. The only reason why things are not even worse than they are is that high inflation boosted tax revenue for two years.

Now that inflation is basically gone, there is no way for the governments in the European Union to buy themselves more time. Either they own up to unending budget deficits and engage in structural spending reductions, or they will face a public finance meltdown that will dwarf the austerity crisis of 2010-2014.

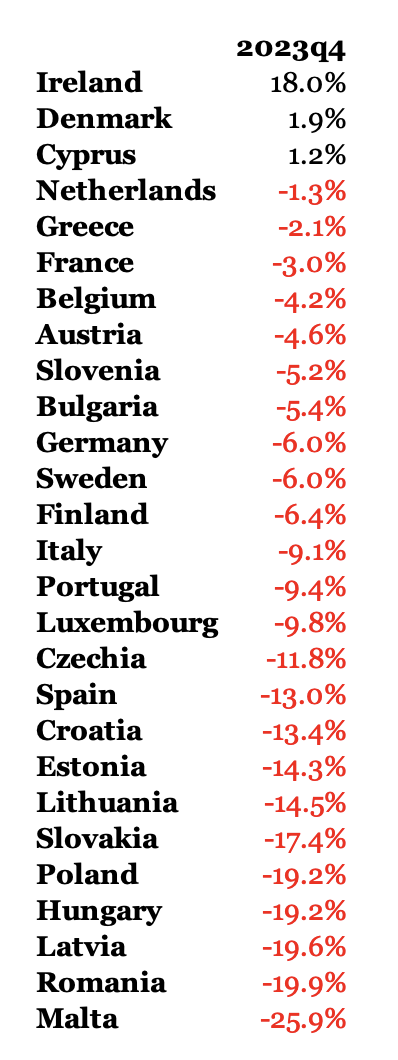

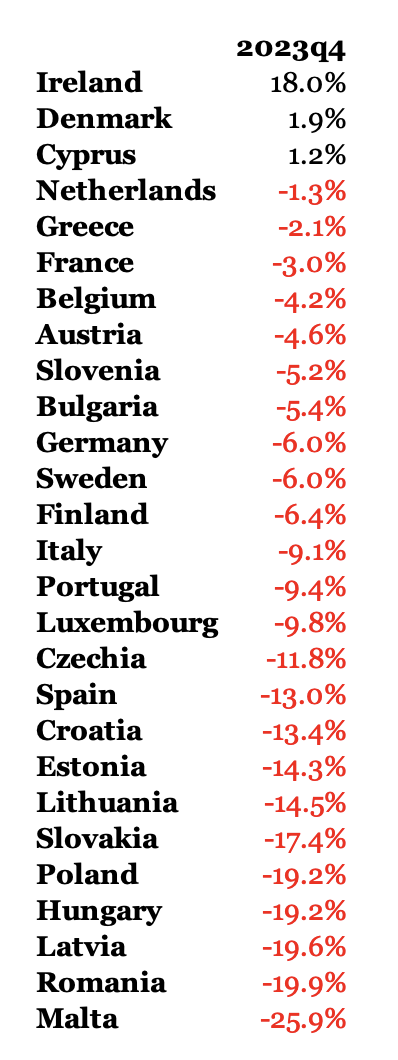

Let us start with budget deficits, of which there are plenty around the EU. In the fourth quarter of 2023, only three countries ran a budget surplus: Cyprus, Denmark, and Ireland. All the other EU members ran deficits, of which 11 had deficits in excess of 10% of government spending:

Table 1

These numbers tell us that Danish taxpayers paid DKK101.90 in taxes for every DKK100 they got in cash and in-kind services from their government. By contrast, taxpayers in Malta delivered only €74.10 in taxes for every €100 they got in goods, services, and cash from their public sector.

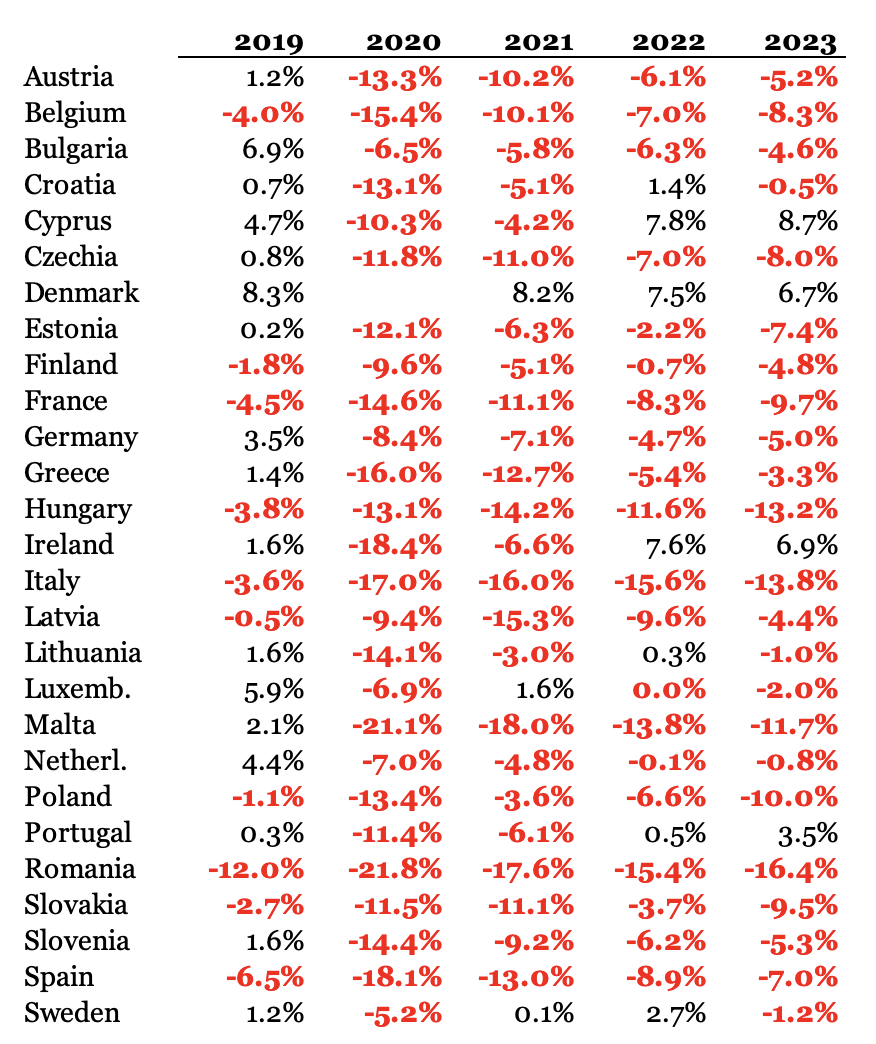

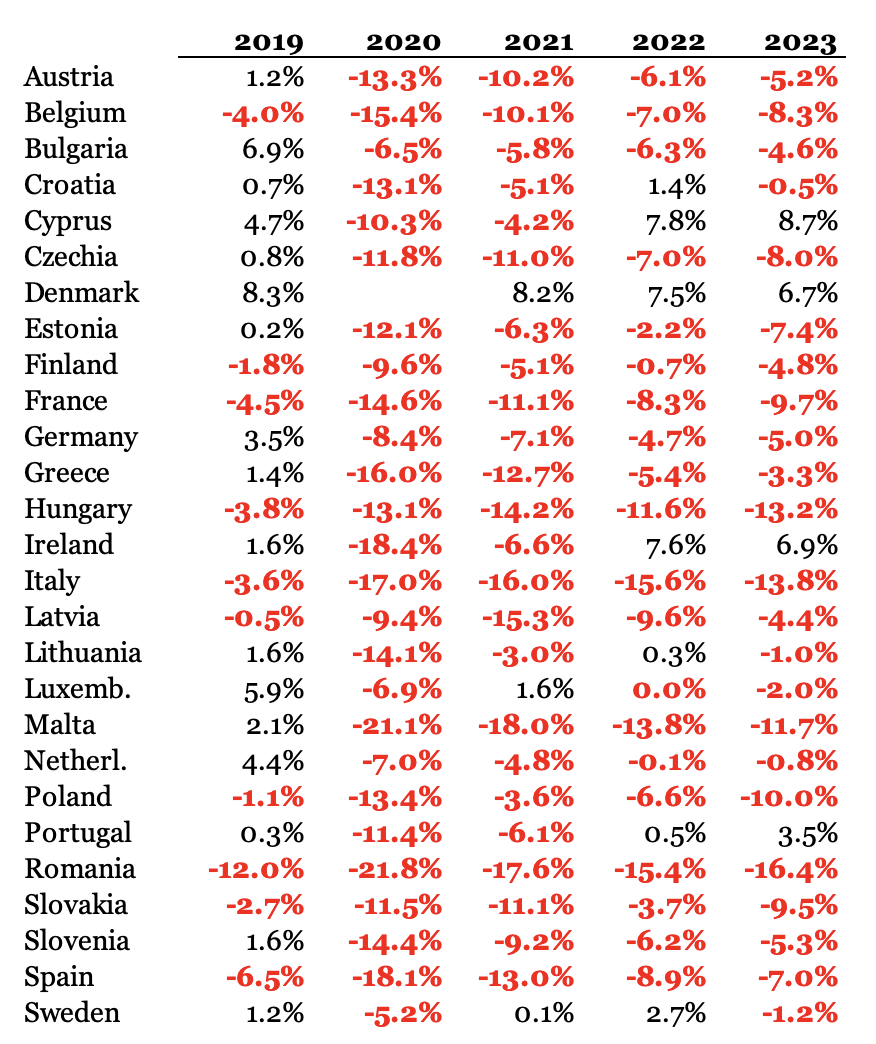

The deficits would not have been such a problem if they were aberrations from an otherwise positive trend. Unfortunately, they are not. Table 2 reports full-year averages for the same numbers as in Table 1, for the last five years. In 2019, there were 10 countries with consolidated budget deficits, but only Romania had an outlandish fiscal shortfall of 12% of total government spending. Starting in 2020, finding countries with a deficit below 5% is a challenge; finding one with a surplus is even tougher:

Table 2

In fairness, the average full-year deficit is declining: after having been only 4% in 2019 among the 10 ‘deficit nations’ and having risen to 12.8% in 2020, the average fell to 9.5% in 2021 (24 states), 7% in 2022 (20 states), and 6.7% in 2023 (23 states).

This downward trend in deficits would be something to celebrate if it was driven by consistent restraint in government spending. In 20 of the 27 EU member states, annual government spending was at least 25% higher, on average, in 2022 and 2023—when the pandemic effect is gone—than it was in 2019.

In Italy, where the government exercised laudable restraint in 2019 and only grew spending by 1.6%, the growth numbers for 2022 and 2023 were 7.6% and 4.2%, respectively. This means that the Italian government increased spending in those two years by €2.66 for every €1.00 that it grew spending in 2019.

Latvian government spending grew twice as fast in 2022 and 2023 as it did in 2019. The same happened in Belgium, Luxembourg, and Poland.

Only four countries had a more modest spending growth in the last two years than in 2019: Germany, Ireland, Malta, and Romania. However, it is worth noting that in Romania back in 2019, government outlays expanded by nearly 16.9%; the annual growth rate fell to 16.5% on average for 2022 and 2023. In other words, what looks like fiscal restraint is in reality only a continuation of a massive expansion of the public sector.

With these expansionist numbers for the outlays side of the government budget, it is nothing short of a miracle that budget deficits are not bigger than they are. That miracle—cynically speaking—is called inflation; thanks to

- Rising prices on goods and services that are taxed with the VAT and with assorted excise taxes; and

- Rising wages to compensate for inflation,

European governments have seen their revenue increase by 10.3% per year in 2022 and 2023, compared to 5.6% in 2019.

In 2019, only one country saw its tax revenue grow by double digits: Romania, at 12%. By contrast, in 2022, there were 14 countries in the 10%+ revenue-growth group, with Bulgaria and Hungary reporting 20%+ increases. In Greece, the revenue increase in the last two years has been 16 times bigger than in 2019; Belgian tax revenue is growing seven times quicker now than before the pandemic.

These numbers are problematic because they have helped conceal the underlying problem with structurally unsustainable growth rates in government spending. Once inflation is weeded out of tax revenue, a grim fiscal reality will set in: the EU member states will have to come to grips with the fact that growing spending by an average of 9.6% per year—as they did in 2023—is downright reckless.

The situation looks even more hopeless when we turn to government debt. The ratio of debt to GDP is rising—even as GDP and, as mentioned, tax revenue is propped up by inflation. Five EU member states have a debt-to-GDP ratio that was at least 10 percentage points higher in 2023 than in 2019; in another 16 states, the debt-to-GDP ratio increased by 5-10 percentage points.

Only Ireland experienced a decline in the ratio.

In 2019, the unweighted average debt ratio among the 27 EU states was 64.8%; in 2023 it had risen to 71.7%. Consistently, 13-14 member states exceed 60% of GDP in debt—which means that half the union is in ongoing breach of one of the fiscal criteria in the stability and growth pact.

On top of that, 7 countries had debt above 100% of GDP in 2023; four years earlier, that number was 5 countries.

The underlying problem for the European Union is that its member state economies for the most part are not growing. Economic stagnation, which is supposed to be exceptional and rare, has become the norm of the day for Europe. The longer stagnation rules the economy, the more difficult it will be to break its shackles—and the easier it will be to run your government finances into the ground.

Which, sadly, with very few exceptions is precisely what is happening right now.