When Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Hungary last week, he arrived to one of the few places in the European Union where his country is considered an indispensable ally rather than a rival. By the time he left on May 10, he’d secured deals that provide fertile ground for China’s plans of economic expansion in Europe.

After meeting with nationalist Prime Minister Viktor Orbán on May 9, the leaders addressed a small group of select media in Hungary’s capital, Budapest, announcing the formation of an “all-weather partnership” that would usher in a new era of economic cooperation.

As most EU countries make efforts to “de-risk” their economies from perceived threats posed by China, Hungary has gone in the other direction, courting major Chinese investments in the belief that the world’s second-largest economy is essential for Europe’s future.

While Mr. Xi and Mr. Orbán didn’t unveil concrete agreements following their meeting, Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó later said in a video that a deal had been reached on a joint Hungarian-Chinese railway bypass around Budapest, as well as a high-speed train link between the capital and its international airport.

The two countries also agreed to expand their cooperation to the “whole spectrum” of the nuclear industry, Mr. Orbán said, and deals were reached on China helping Hungary build out its network of electric vehicle charging stations and on construction of an oil pipeline between Hungary and Serbia.

Zsuzsanna Vegh, a program assistant at the German Marshall Fund and visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said those deals were “a clear signal that China sees Hungary as a key and reliable ally” in the EU as it seeks to reverse Europe’s toughening de-risking policy.

Mr. Xi’s visit, Ms. Vegh wrote in a statement, shows that Hungary’s government “remains indifferent to its allies’ concerns and will continue to strengthen its bilateral ties with China in order to position itself favorably in what it perceives as a developing multipolar world.”

Pursuing a similar strategy is Serbia, Hungary’s neighbor to the south, which has also provided wide opportunities for Chinese companies to exploit its natural resources and carry out large infrastructure projects.

Like Mr. Orbán, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić has built a form of autocratic governance that eschews the pluralism valued in more traditional Western democracies – making both countries attractive to China as opaque direct deals help to eliminate red tape.

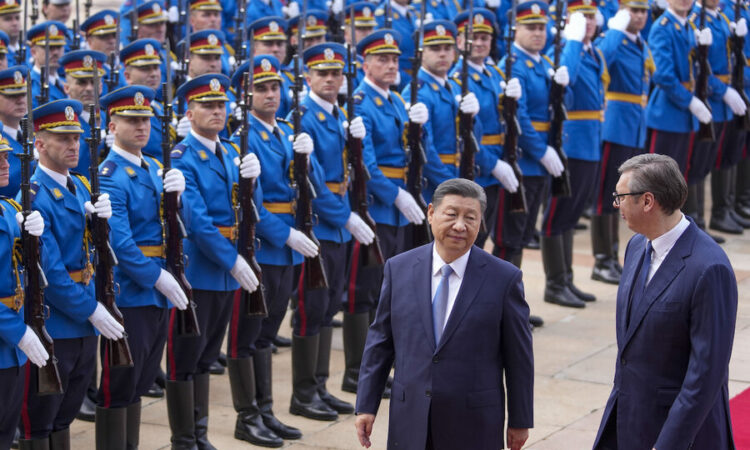

During Mr. Xi’s visit to Serbia last week, he and Mr. Vučić signed an agreement to build a “shared future,” making the Balkan country the first in Europe to agree on such a document with Beijing.

Vuk Vuksanović, a senior researcher at the Belgrade Center for Security Policy, said that Mr. Xi’s interest in Serbia reflects his strategy of appealing to countries that are less committed to a U.S.-led economic and political community.

Mr. Xi’s “shared future” agreement with Belgrade, Mr. Vuksanović said, promotes “China’s vision of the international order, the one where China is much more powerful, the one where the Western powers, primarily the U.S., no longer have the ability to dictate the agenda to others.”

China has poured billions of dollars into Serbia in investment and loans, particularly in mining and infrastructure. The two countries signed an agreement on a strategic partnership in 2016 and a free trade agreement last year.

While Serbia formally wants to join the 27-nation EU, it has been steadily drifting away from that path, and some of its agreements with China aren’t in line with rules for membership.

Mr. Vučić is friendly with Russian President Vladimir Putin, and has condemned Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine but refused to join international sanctions against Moscow.

The red-carpet treatment by Serbia and Hungary has worried some of their Western partners, which see China’s incursion into the region as both an economic and security risk. According to Gabriel Escobar, U.S. envoy for the Western Balkans, Mr. Xi chose to visit the neighboring countries because they “are open to challenging the unity of the Euro-Atlantic community.”

“We caution all of our partners and all of our interlocutors to be very aware of China’s agenda in Europe,” Mr. Escobar said last week.

In February, Hungary followed Serbia’s lead by concluding a security agreement with Beijing whereby Chinese law enforcement officers would be permitted to assist their Hungarian counterparts in police actions within Hungary.

The government has said the officers will ensure public safety among Chinese tourists and members of Hungary’s large Chinese diaspora. But critics say the officers could be used as an extension of Mr. Xi’s single-party state to exert control over the Chinese community.

As Mr. Orbán has deepened relations with Beijing, he has also been engaged in a protracted conflict with the EU that has seen billions in structural funds frozen to Budapest over concerns that he has captured democratic institutions and abused the bloc’s funds.

That money shows no sign of arriving any time soon, and Hungary’s pursuit of additional Chinese developments shows its government “does not envision the possibility of financing such strategic infrastructure projects from EU funds,” Ms. Vegh wrote.

While the inflow of Chinese capital is a boon to Hungary’s sputtering economy, having production sites on EU territory also helps Beijing to circumvent costly tariffs and Europe’s increasingly protectionist policies.

In December, Hungary announced that one of the world’s largest EV manufacturers, China’s BYD, will open its first European EV production factory in the south of the country, and has invited large direct investments in the production of EV batteries.

Such investments, Mr. Orbán said May 9, are what will keep Hungary competitive in the future, from wherever they come.

“The concept driving the Hungarians is that we want to win the 21st century, and not lose it,” he said.

This story was reported by The Associated Press.