EDITORS’ PICK

Complimentary access to top ideas and insights — curated by our editors.

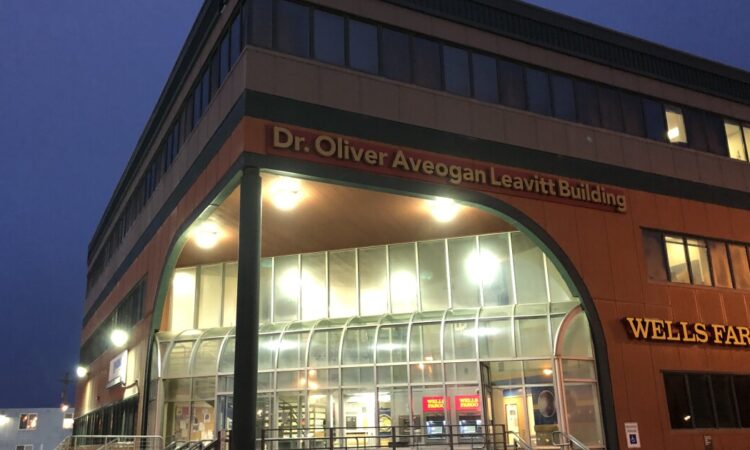

UTQIAGVIK, Alaska — The lone bank branch in town stands just one block away from the Arctic Ocean. Customers trickle into the building, rushing indoors to avoid the 17-degree weather on a breezy December day.

It’s pitch-black outside for most of the day this time of year in Utqiagvik, the northernmost U.S. city. It’s at the very top of Alaska, reachable only by planes from hundreds of miles away.

Some customers walk or drive to the branch. A few come by four-wheeler ATVs or snowmobiles that locals call “snow machines,” which drivers put in idle while they go in to deposit money. Others take a flat-rate $6 cab, visit the ATM and come right back out.

Many customers say they feel happy with Wells Fargo, the country’s fourth-largest bank and one that’s spent years trying to rehabilitate its image following a series of consumer abuse scandals. Though there are some complaints, many say they like the branch’s six employees and feel at home.

“They’re almost like family now,” Teodoro Aguilar López, 60, said in Spanish. He moved to Utqiagvik from Mazatlán, Mexico, more than two decades ago.

But a common feeling among residents is that they want more choices.

“They’re the only choice we’ve got,” said John Stoffa, 50. “They do me good. I have never had any problems with them, but it’s always good to have options.”

A desire for more banks reflects a challenge for consumers in rural parts of the United States, whether in the northern tip of Alaska or in the lower 48 states. Access is even more limited in “banking deserts” where there’s no branch nearby, such as villages across Alaska or rural areas in other states where banks have steadily shuttered branches.

Polo Rocha

Some in Utqiagvik specifically clamor for Alaska USA Federal Credit Union, which has online banking customers in Utqiagvik but lacks a physical presence here.

“Come on up, Alaska USA. We want you,” said a woman in her 40s who uses both Alaska USA and Wells Fargo, and did not want to be identified publicly. Others also requested anonymity to talk about their bank in a small community.

In a statement, Wells Fargo said it’s “committed to meeting the unique needs of the community” and that its customers “value the personal connection they have with our branch bankers.”

“Wells Fargo’s branches across Alaska continue to play an important role in the way we serve our customers in the state, including in rural communities like Utqiagvik where other financial institutions have not made the same commitment,” the company said.

Some 5,000 people live in Utqiagvik, which in 2016 narrowly voted to change its name from Barrow, and more than half of the residents are Alaska Natives.

The Wells Fargo branch displays some of the history of the Iñupiat people, whose roots in the region go back thousands of years. A mural inside includes a 1930 beachside photo of an “umiak,” the kind of boat that the Iñupiat still use to hunt whales, next to an arch made out of the bones of a bowhead whale.

Another wall by the entrance has a photo of Wells Fargo’s iconic horse-drawn carriage, and a painting of a polar bear climbing out of the water and onto an ice sheet. It’s not unheard of for polar bears to wander into town.

No change on the horizon

It doesn’t appear that Utqiagvik residents will get another bank branch anytime soon.

Alaska USA, which over the years has expanded in other states, did not respond to several requests for comment on whether the credit union would consider opening a branch in Utqiagvik.

The $12 billion-asset credit union had a branch in the city going back to at least 1975, according to a National Credit Union Administration quarterly report that included a photo of the branch. It’s not clear when the branch closed, but by 1998, the credit union’s website did not list the city among its locations, according to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

Other institutions contacted by American Banker don’t have plans to expand in Utqiagvik anytime soon. Northrim Bank has no plans for an Utqiagvik branch in 2023 but is “always considering ways we can connect with Alaskans for their banking needs,” spokesperson Kari Skinner said. In December, Northrim opened a branch in Nome, a western Alaska city that is more than 500 miles away from Utqiagvik and is also a “hub” city for nearby villages.

A top executive at First National Bank Alaska, which last year celebrated its 100th anniversary, said it’s “becoming harder and harder” to justify opening a branch in some areas as consumers’ adoption of online banking brings less foot traffic.

“I think we will continue to see challenges with bank branches in more remote locations, and I don’t think that’s unique to Alaska,” said Karl Heinz, First National Bank Alaska’s branch administration director.

Lack of options can be ‘pretty tough’

At least for some, the lack of options has been frustrating.

Wiley Contrades, a self-described “60-plus” Utqiagvik resident, said it often feels like branch decisions are made elsewhere. Although she likes the branch’s longtime employees, Contrades said they often can’t resolve issues without contacting Wells Fargo offices outside the city.

“They’re limited to what they can do,” Contrades said.

She also said Wells Fargo’s fees are “harsh,” specifically calling out a $10 fee for cashier’s checks and a $5 one for money orders.

Another resident, who is in his 30s and asked to remain anonymous, said Wells Fargo shut him out of loans when he was younger. His credit score had suffered from a small leftover fee for a canceled phone contract that went to collections, prompting Wells Fargo to reject him for a small loan as he sought to rebuild his credit, he said.

“Wells Fargo wasn’t willing to help us, but Alaska USA jumped right at the opportunity and coached us through how to build your credit,” he said, adding that he got a $300 personal loan from the credit union and a $500 credit card “all in the same sitting.”

Asked whether he likes Wells Fargo, he said, “It’s good because it gives us a local option, but it’s pretty tough because they kind of have a chokehold on us.”

In its statement, Wells Fargo said its branch bankers “provide important financial guidance and competitive products and services,” ranging from common branch activities like deposits to teaching customers how to use their mobile and online banking tools.

A long history in the city

Wells Fargo acquired the branch in the early 2000s as part of a national expansion strategy. But the branch has been operating since April 17, 1962, when it opened as a branch of Nome-based Miners and Merchants Bank.

On its opening day, the bank gave away prizes to people who walked into its doors and a gift to whoever opened accounts, according to archives of the Nome Nugget newspaper. An F-27 airplane flew in from Nome, sponsored by that city’s chamber of commerce for those who wanted to attend the grand opening.

Miners and Merchants Bank, which dated back to 1904, was acquired by Alaska National Bank of Fairbanks in the late 1960s. The merger was partly driven by staffing concerns, given that Miners and Merchants “had difficulty in attracting management because of its remote location and the severe climatic condition,” according to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s decision to approve the merger in 1969.

Polo Rocha

That bank, which later went by Alaska National Bank of the North, failed in 1987. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. moved its deposits to the National Bank of Alaska, which was the state’s largest bank after steadily growing for decades under the Rasmuson family’s leadership.

Then in 1999, Wells Fargo agreed to buy National Bank of Alaska and its 54 branches for $907 million. In the announcement, then-Wells Fargo CEO Richard Kovacevich praised the Rasmuson family for the “historic role they’ve played in the development of Alaska’s economy and culture.”

The bank’s former chairman, Edward Rasmuson, said at the time that “the decision to sell was not easy.” His grandfather had become the bank’s president in 1919, shortly after its founding. But the financial services industry’s continued consolidation highlighted “the challenge of a regional bank surviving with the changing financial climate that is upon us,” he said.

“To adequately compete, I have always said that we need to be part of a large financial company,” Rasmuson said, while assuring customers that the bank’s commitment to Alaskans “would continue to grow under the new Wells Fargo.”

At the time of the merger, a few community groups warned regulators that Wells Fargo might decide to shut down branches in rural Alaska.

In the two decades since, Wells Fargo has fully only exited one Alaska community: Metlakatla, an island community that is a 45-minute ferry ride away from a Wells branch in Ketchikan. The bank has also trimmed its branch footprint in Anchorage, Fairbanks, Juneau and a couple of other cities.

“I work out in all these remote places around the state, and they always seem to have a Wells Fargo,” said Charles Mullen, who just moved back to Utqiagvik to work at the school district. “So that’s really why I’ve stuck with them.”

Credit questions

Robyn Burke, 31, the executive director of human resources at Iḷisaġvik College in Utqiagvik, has been a Wells Fargo customer her entire adult life and said the branch staff is “really great.”

“When you walk in the door, they greet you by your name,” she said.

But when she bought her first car, she applied for a loan with Alaska USA based on recommendations from others that it’s easier to get approved for credit there.

Data on that question is only available for mortgages, which shows Alaska USA and its mortgage subsidiary approved roughly 71% of applicants in the region who sought to buy a home between 2010 and 2021. Wells Fargo’s rate for approving loans was lower at 64%, according to Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data. The fair lending analytics company FairPlay AI conducted the analysis on behalf of American Banker.

The data is hard to draw conclusions from, given the limited amount of homes available to purchase and overall small amount of loans. But the figures showed Wells Fargo had virtually no disparities in its loan origination rates for Native and white applicants, while Alaska USA was slightly more likely to approve white applicants.

The credit union had more significant disparities for the 60 applicants who sought to refinance their home during that time period. Alaska USA approved 43% of Native borrowers who sought to refinance, compared with 69% of white ones. Wells Fargo had virtually no such disparities in originations among its 84 refinance applicants.

Alaska USA did not respond to requests for comment on its mortgage lending record.

Wells Fargo said it’s engaged with government officials, Alaska Native organizations and community groups to tackle the various housing-related challenges residents face. Those challenges include “a very low inventory of single-family, owner-occupied homes, limited access to building materials, short building seasons, and few incentives for developers to build more homes,” the bank said.

Wells Fargo ‘done just fine for us’

But even if Alaska USA comes to town, some local residents probably wouldn’t make the switch.

Jennie Elavgak, who switched to Wells Fargo last year, likes the bank because her direct deposit lands quicker than it used to at Alaska USA. She said the credit union’s slower service caused her to miss a couple of bill payments. Alaska USA did not respond to questions about her issue.

Elavgak, who is graduating from high school this year, described Wells Fargo as a family-oriented bank that helps parents save for their kids’ college education and open up bank accounts for them.

“It’s just a welcoming branch,” Elavgak said before hopping back on her snow machine and leaving the parking lot.

Geoff Carroll, a retired fish and game biologist, brought up Wells Fargo’s ongoing regulatory troubles, stemming from the fake-accounts scandal that exploded in 2016.

“It’s kind of scary when you hear the national news,” Carroll said. “Seems like Wells Fargo is always in trouble for something or other. It makes you kind of wonder.”

But he said Wells Fargo has “always done just fine for us.”

Stoffa, meanwhile, said he likes Wells Fargo because it’s “right here in town” and provides “excellent” customer service. Stoffa used to bank with Alaska USA, but he said he got tired of “having to deal with them over the phone all the time.”

The banking industry is increasingly relying on phone support and mobile apps to help customers. But those actions risk losing customers like Stoffa, who said he prefers working out any issues in person.

“Having that face-to-face communication with a banker is always good,” Stoffa said.