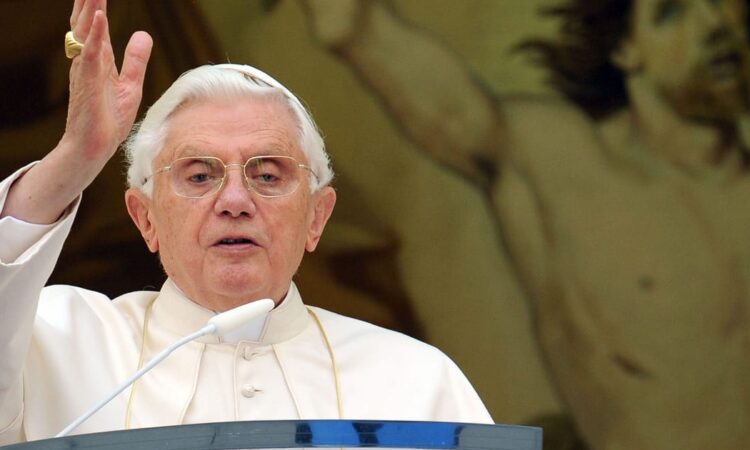

When Pope Benedict XVI in 2013 became the first pope in six centuries to resign, he promised to remain hidden from the world in silence and prayer.

In the tiny Vatican City, surely not big enough for two popes, this would give his successor the best chance of stamping his authority on the papal post.

Benedict XVI’s professed physical frailty meant that he was not expected to live long. But cared for by a quartet of devoted nuns, Benedict remained a presence in the Vatican and the Catholic Church for almost another decade, dying on Saturday aged 95.

For the first few years after his resignation, Benedict XVI made few appearances and published little in writing. But later he more freely expressed opinions on reforms, becoming a focal point for conservatives who wanted to create a parallel court and challenge the legitimacy of Pope Francis. Francis biographer Austen Ivereigh has suggested that Benedict had been manipulated by conservative clerics.

Despite the divisions caused by the enduring presence of a second pope in the Vatican, Benedict XVI will be remembered for the humility of his gesture to resign, stepping back to allow the efforts at reform of the church that he himself was incapable of accomplishing.

Joseph Ratzinger, who became Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, was born in 1927 in Germany’s Catholic heartland of Bavaria. The Ratzingers had been a poor farming clan, but Joseph’s father was a police commissioner and his mother a hotel cook. Ratzinger joined the Hitler Youth as a 14-year-old and later served in the German armed forces, but an investigation by the Simon Wiesenthal Center found the Ratzingers came from a family of anti-Nazis, with no hint of anti-Semitism.

After World War II, he entered a seminary with his older brother Georg, with whom he remained exceptionally close until Georg’s death two years ago. When Joseph was made pope, Georg was concerned about his brother’s strength holding up under the pressures of office. Georg, who had been looking forward to retiring together with Joseph to Germany, said he was “not very happy.”

Ratzinger earned a doctorate in theology at the University of Munich and then became a teaching academic. While as pope he did not have the renowned charisma of his predecessor, John Paul II, his students described an inspiring teacher, and his formidable intellect made him one of the leading theologians of his time in the eyes of many conservatives.

He was selected as expert assistant by the archbishop of Cologne for the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council, which brought sweeping reforms to the Church. At the council, he was among the reformers, but the student protests and denunciations of Christianity he witnessed in the late 1960s reminded him of the Nazis and he became more conservative.

Pope Paul VI elevated him to cardinal. And his friend Pope John Paul II appointed him as head of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, the Vatican ministry for doctrine and discipline. In this role, he was responsible for dealing with clerical abuse, which led to criticism of his conduct when the crisis emerged, and this reproval followed him into his papacy.

‘God’s Rottweiler’

When he was elected pope in 2005 in an unusually short two-day conclave, it was as a continuity candidate who would maintain John Paul II’s traditionalist line on celibacy, contraception and sexuality.

As pope, Benedict XVI was deeply conservative, seeing the church as a barricade against secular trends in Western society, particularly what he called the “dictatorship of relativism.” His view was that Catholics should foster a fortress mentality, holding that perhaps a smaller, “purer” church would better guard Catholicism’s traditions and teachings.

Critics called him “God’s Rottweiler” for his staunch adherence to doctrine and his intolerance of dissent.

His papacy was noteworthy for his outreach to other religions, even offering Anglicans a chance to convert while maintaining some of their traditions, which however was seen as an act of war by the Church of England.

By the end of Benedict’s papacy, the Curia, or Vatican civil service, divided by rivalries and suffering from mismanagement, had become “a nest of crows and vipers,” according to Benedict’s number two, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone.

In what became known as the “Vatileaks” scandal, Benedict’s personal butler leaked thousands of documents claiming that the Curia was permeated by powerful gay lobbies and that the Vatican bank was corrupt, a tool for money-laundering and used by terrorist organizations.

Lacking the strength and energy to tackle the charges of corruption, Benedict renounced power, permitting the election of an outsider who it was hoped could clean up the Vatican.

For the last 10 years of his life, Benedict lived in the Mater Ecclesiae monastery inside the Vatican, spending most summers in the papal summer palace of Castel Gandolfo.

The adoption by his successor, Francis, of a humble lifestyle in a priest’s guesthouse was an implicit criticism of Benedict XVI and his regime.

While expressing respect for one another, the two pontiffs continued to jar on reforms. Benedict condemned the lifting of priestly celibacy when Francis was considering a partial relaxation of the rules. While Francis has accepted the church’s responsibility for the clerical abuse scandal, Benedict has blamed external forces such as the 1960s sexual revolution, and lamented that the revelations have contributed to the crisis in priestly vocations.

In an authorized 1,000-page biography by Peter Seewald titled “Last Questions to Benedict XVI,” Benedict denied meddling. “The claim that I regularly interfere in public debates is a malicious distortion of the truth,” he said.

Some of the fiercest criticism of Benedict XVI came from his home country of Germany, where reformers have been attempting to repair the church’s reputation and open discussions on celibacy, the role of women and church power structures. Benedict, had he lived, was due to face a civil trial in 2023 in Bavaria for mishandling of abuse allegations in the 1970s and 80s when he was archbishop of Munich and Freising. Benedict denied wrongdoing in that case but asked for forgiveness for mistakes.

Benedict XVI leaves a mixed legacy, but he will be remembered for charting new territory as the first modern pope to resign from St. Peter’s Throne — a precedent that may serve to normalize the resignation of future popes.