Published as part of the Financial Stability Review, November 2020.

Rising sovereign debt in the wake of the pandemic has renewed concerns about the euro area sovereign-bank nexus ‒ a major amplifier in the euro area sovereign debt crisis. In the early 2010s, banks in a number of euro area countries held high shares of their government’s debt at the same time that governments were providing guarantees or other support to their banking systems. In recent years, many euro area countries have observed a decline in sovereign-bank interlinkages and, in turn, in the risk of intertwined crises. However, the pandemic and the fiscal measures to support the economy that followed are likely to prompt an increase in sovereign debt, and in turn in the exposures between governments and their banking systems. In addition, the sovereign-bank nexus may develop also via indirect channels, including banks’ exposure to the state of the domestic economy; whereby direct holdings can amplify these indirect effects. This box assesses how the interlinkages, via the direct exposures of banks to sovereign debt securities[1], have increased so far and whether this has led to an increase in crisis risk.

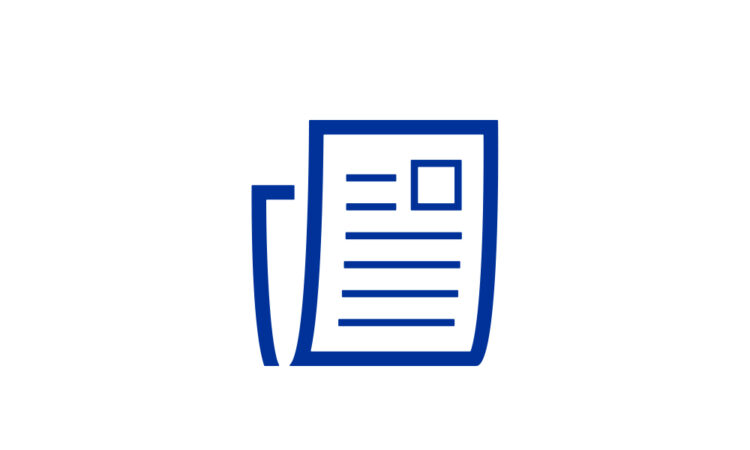

Chart A

Banks have already increased, and could further increase, their exposures to domestic sovereign debt securities, although they play a less significant role as investors in these securities

Sources: ECB (balance sheet items, government debt and sectoral securities holdings statistics, and macroeconomic projections).

Notes: Left panel: shows observed data until September 2020 and a potential forward-looking development for the end of 2022. The end-dot gives a simple projection of potential increase based on the average share of domestic sovereign debt securities held by euro area banks in the period from March to September 2020 (i.e. since the outbreak of the pandemic), and projected public debt developments from 2020 to 2022 (from the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area), other things being equal. Given the implementation dates of the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) (currently set at least until June 2021), the share applied from September 2020 to June 2021 takes into account the ongoing Eurosystem net asset purchases for the announced period. The share of domestic sovereign bonds held by euro area banks is conditional on multiple incentives for banks coming from future developments in macroeconomic conditions, monetary and prudential policies, public finances and financial markets: changes in these conditions and policies may affect banks’ incentives. Middle panel: the Eurosystem holdings considered within or outside of the outstanding amount of sovereign debt securities refer to the cumulated holdings under the PEPP, the public sector purchase programme (PSPP) and the Securities Markets Programme.

In 2020 to date, euro area banks’ exposures to domestic sovereign debt securities have risen by almost 19% in nominal amount – the largest increase since 2012.[2] This reflects banks’ role in absorbing a significant share of the higher issuance of government debt to fund fiscal support measures, as well as banks’ decision to invest the increased amount of deposits in low-risk assets including government bonds (see Chart A, left panel). But the share of total assets invested in domestic sovereign debt securities varies across countries. Since the beginning of 2020, it has increased in a range between 0 and 1.6 percentage points. It is now equal to 11.9% for Italian banks and 7.2% for Spanish banks, but close to 2% for French and German banks.[3] If banks increase their holdings in line with projected increases in fiscal debt over the next two years, these exposures could increase by a further 0.8-4.7 percentage points of total assets (1.6 percentage points for the euro area), other things being equal. However, the future path of banks’ exposures to domestic sovereign debt securities depends on multiple factors. At the country-level, these factors include the pace of increase of domestic sovereign debt in the coming months and the asset purchases by the Eurosystem (under the PSPP and the PEPP), and at the bank-level, potential carry trade incentives, regulatory compliance with capital and liquidity requirements, as well as collateral needs for the participation in the Eurosystem refinancing operations. Furthermore, before the pandemic, euro area banks were holding a declining share of the sovereign debt securities issued, even after excluding Eurosystem holdings from the outstanding domestic sovereign debt (see Chart A, middle panel).

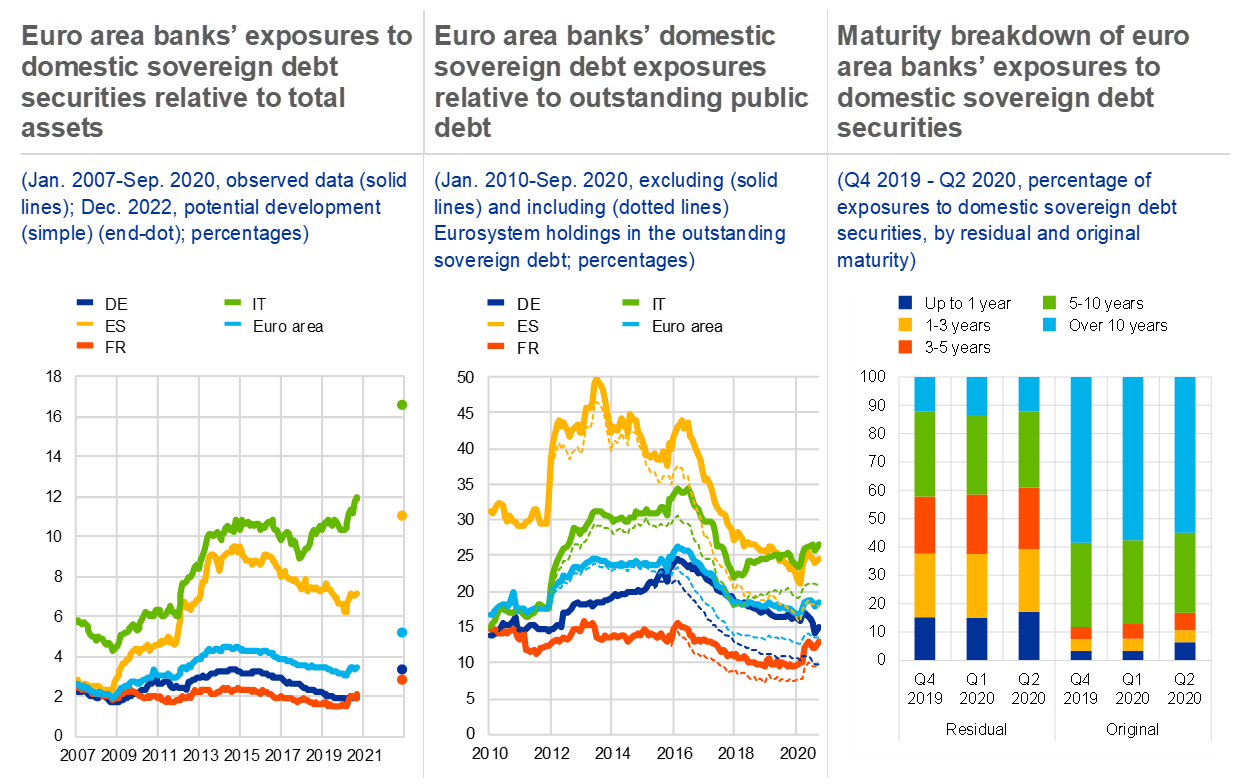

Chart B

So far, valuation changes in banks’ portfolios of sovereign debt securities have had only modest effects on capital positions

Sources: ECB securities holdings statistics, ECB supervisory data and Bloomberg Finance L.P.

Notes: The charts refer to the sample of euro area significant banking groups reporting security-level holdings data. Left panel: weekly valuations of the portfolios of sovereign debt securities held at fair value for banks in selected countries. The composition of the portfolios of sovereign debt securities is determined based on the holdings as at the end of the fourth quarter of 2019 for the first quarter of 2020, but it accounts for the changes in holding amounts at the end of the first quarter of 2020 for the second quarter of 2020, and at the end of the second quarter of 2020 for the developments in the third quarter of 2020. Right panel: the stacked bars distinguish the changes due to the exposures to sovereign debt securities held at fair value through profit or loss under the application of prudential filters, and the changes due to the exposures to sovereign debt securities held at fair value via other comprehensive income in the absence of prudential filters.

So far, the vulnerability of banks to higher holdings of sovereign debt securities has been contained because valuation changes have been modest. Monetary policy measures and the proposal for the EU recovery fund in May, reversed initial valuation losses in portfolios of sovereign debt securities (see Chart B, left panel). In addition, less than half (47%) of banks’ exposures to sovereign debt is currently subject to fair value accounting, and in response to the pandemic authorities temporarily reintroduced prudential filters for sovereign debt securities held at fair value through other comprehensive income,[4] which mitigates the impact of valuation changes on CET1 ratios (see Chart B, right panel).

But with sovereign debt positions expected to remain elevated for some time, vulnerability to valuation changes will persist and other sovereign-bank linkages could also increase. The rise in public debt could be more sizeable in the future if the contingent liabilities from loan guarantee schemes were to materialise, resulting in additional public debt. Domestic banks, especially in countries where governments have higher credit risk and/or banks are less capitalised, could face pressure to support governments under fiscal pressure. Furthermore, independently from direct exposures, an increase in public debt may affect domestic banks also via indirect channels, including a negative impact on their debt financing conditions.