In the next mandate, the EU needs to set clear rules for private investment in the green transition, to avoid past mistakes.

The financing of a just green transition requires both private and public capital—on that there is consensus. There is, however, less agreement on the regulatory framework.

The capital-markets union pursued by the previous European Commission sought mainly to mobilise private capital via financial deregulation, while paying little attention to the outworking of the deregulation agenda across Europe. Rolling out the red carpet for private capital risks handing out windfall profits without contributing to sustainable-investment goals, while simultaneously increasing inequality. Instead of continuing down this path, the next commission, emerging after the June elections to the European Parliament, needs to reset the rules for private investment to guarantee the social-ecological transition.

Short-term focus

Deeper European capital markets, while certainly desirable, do not address the short-term focus of publicly traded companies. At a time when investments in sustainable and digital business models are of high urgency, capital is often distributed to shareholders instead.

In the Netherlands, dividends of public companies rose by almost 60 per cent between 2019 and 2022, although profits only increased by 36 per cent. The same pattern can be seen in Germany and France—profit distribution rising at the expense of investment. If the French companies listed in the CAC 40 had distributed only 30 per cent of their profits in 2018, the retained earnings would have covered the sustainable-investment needs for that year, according to the climate disclosure project. Share buybacks also prioritise ‘shareholder value’: this year German DAX companies are planning to repurchase more shares than ever before.

In recent decades, in line with orthodox economics, restrictive fiscal rules and faith in ‘efficient’ private enterprise have led to substantial privatisations in systemically important areas. The argument has been that private finance can bridge the funding gap and manage the offloaded enterprises more efficiently. This is the orthodoxy evoked today to mobilise private capital for the green transition. So how has it worked out in practice?

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

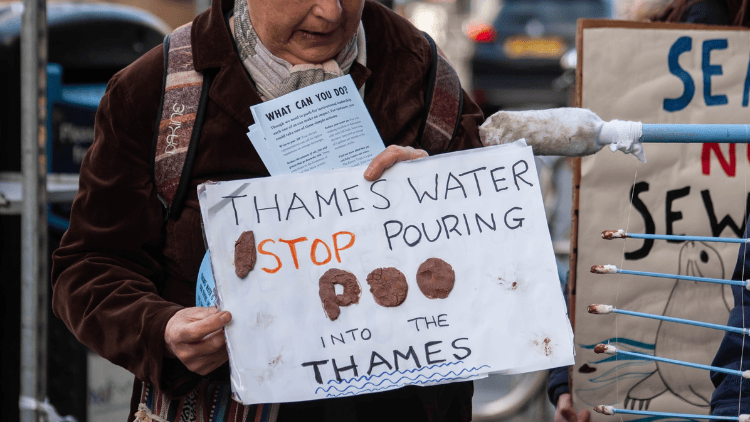

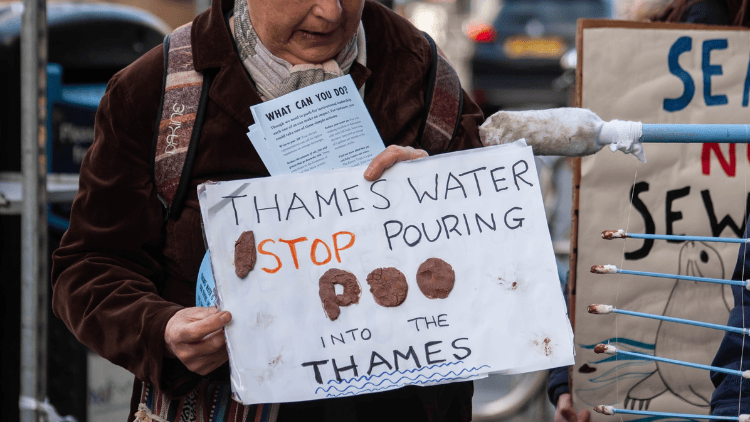

Water companies in the United Kingdom represent an excellent example of misguided financialisation. Privatised in the late 1980s when Margaret Thatcher was prime minister, they have since been restructured by various financial investors and loaded up with debt. While enormous profits were distributed in the past, instead of investing in physical infrastructure, the companies now make headlines with concerns ranging from excessive water losses to devastating environmental pollution.

Thames Water, a provider of services to 15 million households, has been facing insolvency due to over-indebtedness since mid-2023. Renationalisation of the company appears the only solution. This would however mean taxpayers carrying the can for the private investors who previously siphoned off high profits.

Severe consequences

The pandemic highlighted an urgent need for investments in health and social care. For many years, government has withdrawn from this arena, paving the way for the entry of private finance. Far from this leading to increased investment, however, studies of care homes for the elderly across Europe have found profit extraction and accumulated debt. This has increased the risk of bankruptcies, while profits have been channelled to investors via offshore financial centres to avoid taxation.

This has severe consequences for the quality of services provided: a Harvard Medical School study revealed serious health consequences for patients treated in hospitals in the United States owned by private-equity firms. A Swedish study showed that financialised nursing homes provided lower-quality services than homes with other forms of ownership. Vulnerable groups have been directly affected, as evidenced by numerous care scandals in Spain, Germany, France and the UK. These encompass inflated billing costs with substandard care, malnutrition among residents and even elevated mortality in nursing homes with private-equity owners.

Similarly, while government and other non-profit providers have withdrawn from housing over the years, publicly listed companies and financial investors, such as private-equity firms, have moved in and exacerbated social problems. Between 2009 and 2020, the volume of capital invested annually in European residential property rose by more than 700 per cent, to over €60 billion. Yet the deficit in housing supply has increased massively: rents in urban centres have continued to rise, reaching records in some areas. This trend is exacerbated by financial investors, as shown in a recent study by the European Central Bank.

Once again the financialised companies’ focus is on the short-term—not housing development. The latter could actually decrease the share price of housing companies, as mentioned by the German housing giant Vonovia in its 2019 annual report. Investments in maintenance and energy-related renovations likewise represent short-term costs. And again profits are distributed rather than invested: in 2021, 41 per cent of the rent paid to listed housing companies in Germany went directly to shareholders as dividends.

Increased inequality

A system favouring distribution of profits while depressing investment will foster increased inequality: according to Oxfam, global billionaires are already $3.3 trillion richer than they were in 2020, while the poorest 60 per cent of humanity are $20 billion poorer. This is a problem for the green transition, as research suggests higher inequality is linked to lower support for climate policies.

The increase in inequality has been particularly visible in the most recent crises and policy responses. In the Global Financial Crisis, banks were rescued with public money: previous profits had been private, yet their losses were socialised. Increased public debt was then held to merit severe austerity throughout Europe.

During the pandemic, the corporate and financial sector once again benefited from generous crisis policies, such as central-bank asset-purchase programmes. While profits for hedge funds and banks increased, myriad workers across Europe were forced to reduce their working hours and suffered wage losses.

The record of unregulated private-finance involvement in public services is thus rather bleak, tending as it does to prioritise value extraction over value creation in essential sectors. Relying on private finance to foster the green transition is likely to increase inequality further, which in turn could jeopardise social backing for climate policies and even enhance support for populist movements.

Regulation essential

There is no question that private capital will have to play a significant role in the transition. But effective regulation is essential—not just in regulating financial markets directly but also touching on other elements of economic policy.

Industrial policy needs to be subject to conditionality, ensuring that government subsidies are not spent on dividends or share buybacks. To restrict the extraction of profits from public services by financial investors, a payout distribution cap could be introduced for specific sectors, on a European level. This could prevent extractive practices while allowing companies to realise appropriate returns over the long term.

The EU regulation covering alternative investment funds (AIFMD), such as private equity, focuses mainly on the protection of investors while neglecting to protect the real economy. A fundamental revision of the directive could hold financial investors accountable for their risky business models, for instance by introducing liability rules for portfolio companies.

Last but not least, financial stability will be crucial for a successful social-ecological transition. The March 2023 financial crisis showed how unstable the sector remains. Future rescue efforts could divert much needed attention from the transition. There are plenty of reasons for a financial reset.

This is part of our series on a progressive ‘manifesto’ for the European Parliament elections