Elaborate descansos line highways and streets across New Mexico, honoring lives lost. Here, where the pedestrian death rate has led the nation for six years in a row, families go far beyond a simple white cross. They add photos, tend colorful flowers, hang holiday decorations – and state lawmakers have made it a criminal offense to deface them.

In New Mexico’s remote northwest corner, these memorials stand watch over the multi-lane freeways that twist their way from the Navajo Nation and other tribal lands into the small city of Gallup. It’s exactly the type of disadvantaged place the Biden administration promised would benefit from a massive influx of federal money for safer streets. McKinley County is poor and home to Native communities often left out of such programs.

But two years into the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s rollout, many places like Gallup have received little help even as millions go unused, a USA TODAY investigation found. In the $5 billion Safe Streets and Roads for All program, most of the money doled out so far has gone to more affluent counties with lower fatality rates.

That’s because the grants are structured to reward communities that already have the resources to pursue the funding: Detroit, for example, with an 18-member grant writing staff that’s raked in nearly $50 million to improve its streets. Or Montclair Township, N.J., a wealthy New York City suburb where citizens have demanded solutions from elected leaders. It got about $440,000.

Gallup, with no dedicated grant writer, where public meetings on transportation last year drew little interest, never even asked for the money.

Crash records show they could certainly use it.

Screaming train whistles punctuate life in Gallup, as milelong trains barrel along one of America’s busiest freight routes. The switchyard runs parallel to New Mexico’s primary east-west interstate, creating a half-mile-wide chasm for pedestrians between Gallup’s historic downtown and the newer stores and restaurants on the other side.

Rather than take a long walk around, some locals clamber over the tracks and dash across four lanes of 65-mph traffic. Stronger fences or a pedestrian bridge could have kept Jeremiah Begay, 23, from doing that in 2016. He was killed when two tractor-trailers struck him on the highway around sunset.

Years of underfunding mean many city sidewalks are narrow and poorly maintained, if present at all. None existed along the unlit road just outside town where silversmith Roy Johnson died in 2022. Family members say he was walking near his home on a dark night when a Gallup police officer ran him over, but police reports say he was lying in the roadway when he was hit. The family’s wrongful death lawsuit is still pending.

Center lines and crosswalks have weathered away on many city streets. A simple coat of fresh paint or flashing lights might have prevented Navajo elder Benson Daniels’ death in 2021, when a van struck him in a faded crosswalk at a busy downtown intersection. His 26-year-old niece Brandy Grenier wishes someone in Gallup had sought help from the federal government so that no one else is hurt.

“Now that I’m aware of this funding that’s available, I would definitely want McKinley County and the surrounding areas to take advantage of it,” she said.

But, they haven’t, and neither have hundreds of other counties with high fatality rates.

Triumphant press releases have heralded multimillion-dollar grants scattered across the country, most to large cities with their share of dangerous streets. A USA TODAY investigation has found persistent barriers block the neediest communities from winning grants that could save lives:

- The U.S. Department of Transportation is supposed to ensure underserved communities have access to these grants, but the law that created the Safe Streets program never specified how. So, the agency has largely relied on outside organizations, newsletters and webinars.

- The decisionmakers know the trouble spots since they’ve tracked traffic deaths nationwide for half a century. Despite this, agency staff initially told USA TODAY they had not reached out directly to hot spots to drum up interest for the federal funds. Five months after USA TODAY started asking for records of their outreach efforts, they said they have done that kind of targeted communication “in the past few weeks.”

- Department staff use three data points, including fatality rate, to grade applications but it’s unclear how much death played a role in decisions. A USA TODAY analysis shows nearly all of the money has landed in counties the department itself says have low fatality rates.

The Safe Streets program is just one of at least 20 new competitive grants that will divvy up billions of dollars in infrastructure funding over the next few years. Researchers have already pointed out the same few states routinely win this type of grant, and the Government Accountability Office testified before Congress last summer that rural, Tribal and other typically underserved communities often can’t compete.

As the third round of applications opens this week, the transportation department is expanding its outreach to places that need help with traffic safety, said Christopher Coes, assistant secretary for transportation policy, when presented with USA TODAY’s findings.

“We have designed direct outreach,” Coes said. “Each year, we’re doing this data-driven and comprehensive review of where our impact is going really well and where are things that we need to do better.”

Safe Streets Program Manager Paul Teicher said they have developed a list to target. He named Mobile, Ala., as one city they’ve encouraged to apply, along with Hartsville, S.C.

Competitive grants do have their place in rebuilding American infrastructure. Kristin Smith, who researches public finance with Montana-based nonprofit Headwaters Economics, said they can inspire innovative projects across the country.

“But when it comes to funding that is meant to save people’s lives, that’s designed to meet people’s basic needs, a competitive grant, in my opinion, isn’t the right tool,” Smith said. “It’s regressive. You have to have resources to access it.”

Why hasn’t more Safe Streets money been awarded?

Traffic deaths spiked in 2020, even with so many Americans staying home during COVID-19 lockdowns, following an upward trend that began over a decade ago. And that total leapt again in 2021, the latest available from government data, with crashes killing nearly 43,000 Americans that year and injuring roughly 2.6 million.

Our investigation:Here’s how USA TODAY analyzed federal Safe Streets for All grants accross the U.S.

Solutions:Where traffic deaths are high, how can communities get the government’s attention?

“We face a national crisis of fatalities and serious injuries on our roadways, and these tragedies are preventable,” said U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg in a press release launching the Safe Streets program, noting the grants “will help communities large and small take action to protect all Americans on our roads.”

After that announcement, federal officials waited for the applications to roll in for one of the largest competitive grants in the infrastructure law. No one from the transportation department reached out directly to disadvantaged and rural places to tell them about the money.

Gallup, for example. Or rural Robeson County, N.C., where a mostly Native American and Black population struggles with one of the state’s worst fatality rates. Or Clayton County, Ga., just outside Atlanta, where the state has identified crash hotspots where crosswalks are hard to find, spaced a half-mile apart.

Some places figured it out. The Safe Streets program has delivered funding to every state, with over 1,100 awards ranging from just a few thousand dollars for a remote Alaskan village to $51 million for New York City. For hundreds, it’s their first-ever federal grant, Coes said.

The bulk of the funding – about $1.2 billion – has been concentrated in 85 “implementation grants” – large, highly competitive awards to fix problems communities have already identified. New York City plans to use its grants to add bike lanes, elevate crosswalks and build other pedestrian safety measures along dangerous streets in Manhattan and Queens.

Only about one in five places that applied for these grants won, according to USA TODAY’s analysis. To be eligible, communities must have a safety plan that meets all the transportation department’s standards and write up to 12 pages making a compelling case for how the award would fix their safety problems.

“It took five people of our seven-member team here in this department to complete that grant,” said Tomika Monterville, former transportation director for San Antonio, Texas, which won $4.4 million to build mid-block pedestrian crossings along a dangerous, multi-lane street.

“You’ve got to have a good writer; you’ve got to have a keen understanding of all the programs that connect to tell the story of your community,” Monterville told attendees at a Safe Streets webinar hosted by a tech company last spring.

The rest of the Safe Streets money has been split into more than 1,000 smaller grants to help communities study crash hotspots and plan and test ways to address them. The department made applying for these smaller planning grants “as simple as possible” to attract underserved communities who have never gotten federal funding, said Cheryl Walker, associate administrator for safety at the Federal Highway Administration, at the same webinar.

And grant recipients told USA TODAY it wasn’t the typical federal grant, with their pages of forms to complete.

“The maximum narrative was 300 words, so it was like a paragraph. Or half a page, essentially,” said Stephanie Rossi, planning director for the Lowcountry Council of Governments, a partnership that earned nearly $300,000 to draft a safety plan for four of South Carolina’s southernmost counties, including the popular vacation destination Hilton Head Island.

South Carolina had the fourth highest pedestrian fatality rate in the country for 2021, so Rossi said she was disappointed to see just a handful of other places in her state apply in the first round.

“I’m not trying to ding my neighbor,” she said. “Maybe folks didn’t realize the application process wasn’t really that awful.”

Applying for federal grants is typically more complex and time-consuming than state or local grants, and the news of how easy it is to get planning grants didn’t make it to many of the communities that might need them most.

Now, two years into the program, the Department of Transportation has at least $230 million for planning grants sitting unused, simply because too few places applied.

“Every complete, eligible application that came in received an award,” Walker said. “We want every entity out there, all the locals, to have these grants and these action plans in place.”

The agency knows where fatal crashes happen frequently. It’s compiled dozens of details on each crash for nearly 50 years, and last summer, department employees mapped out counties with high death rates. Only about a third of these counties have won any money. USA TODAY requested records showing how the department reached out to these places it labeled as “target areas.”

“They did not engage in reach out to potential individual applicants,” wrote Victoria Schmitt in November. She’s attorney adviser for the department’s Volpe Center, one of several offices that support the Safe Streets program.

Reaching out directly “might be overstepping what the federal government can do,” said Mariia Zimmerman, who leads technical assistance efforts within the transportation department. “If I called your mayor, and I didn’t call another mayor, is that being unfair in calling one versus another?”

But after USA TODAY began asking last fall how the department has directly reached out to needy places with high death rates, they started to do just that. Teicher, the grant program’s manager, said his team has communicated with leaders of two southern cities “in the past few weeks.” They provided a list of 16 other places that have had recent contact with Teicher’s team.

A separate agency team traveled to almost two dozen communities in the last year to encourage applications, spokesperson Sean Manning said, including the Navajo Nation, Arlington, Va., and Las Vegas.

It’s a start, but USA TODAY found over 1,000 counties with above-average fatality rates that haven’t won any money.

Zimmerman said department employees are trying to raise awareness as best they can, but they also have limited time and staff. So, potential applicants must often seek out program details for themselves – whether by asking for help directly, watching the agency’s webinars or subscribing to emailed alerts.

Tens of thousands of local governments nationwide are eligible for funding, yet agency records show three webinars last spring each drew in about 1,000 people. Attendance trickled to just a few dozen as the webinar series continued. Over 19,000 people have signed up for the program’s mailing list.

The federal government also relies heavily on trade organizations like the National League of Cities to help get the word out, according to Coes, the assistant secretary for transportation policy.

“Just because someone from Washington shows up and says, ‘Hey, I’m here to help.’ Not many people actually may trust that. And so, sometimes you have to engage trusted, valued partners,” Coes said. “We’re only halfway through this program, right? We’re recognizing that we’re going to have to marshal all of our resources. And so, for us, hopefully our data can help us fill the gaps and understand where we need to target our limited resources.”

Coes pointed out the Safe Streets program is not the only money available for traffic safety projects, listing hundreds of billions of dollars in other grants. However, Safe Streets was specifically simplified and set up so even the smallest of towns could apply directly for federal money.

Patty Holland, Gallup’s chief financial officer, said her city has several projects that would likely be eligible for Safe Streets funding, but the grant just wasn’t on their radar. Without a dedicated grant writer who can sift through thousands of options, she said they miss a lot of opportunities.

“It’s very, very overwhelming what is available,” Holland said. “We spend so much of our time pursuing all of those new (federal) requirements that change every year, we just don’t have the time to reach out and look for these. And even if they put us on the email list, we’re really not going to recognize a lot of it, because there’s just too much in our email.”

Who is winning federal Safe Streets money?

When communities apply for Safe Streets funding, the transportation department asks for three data points: total roadway deaths, average fatality rate over the past five years and percent of the population considered “underserved.”

Ideally, grants should end up in counties that score highly in all three. However, USA TODAY’s analysis found little correlation between a county’s total funding and those statistics. What most recipients of Safe Streets money do share is a larger population and a strong capacity to apply for grants.

They often have experienced government employees, colleges or universities and an engaged community with high voter turnout, stable incomes and health insurance, said Kristin Smith of Headwaters Economics. Her team developed a tool it calls a “capacity index” to help understand why some communities struggle to access federal funding.

The transportation department has announced about $1.7 billion overall in Safe Streets grants as of December, and 82% of that has gone to counties the index defines as “high capacity,” according to USA TODAY’s analysis. Meanwhile, low-capacity counties have received less than 2% of the money.

“For the rural communities where I work (in Montana), they can barely keep up with day-to-day operations,” Smith said, describing a county without a single engineer, planner or grant writer on staff. “If you add in a federal grant with just one more task, it’s actually a big ask.”

Many of the places least able to compete for grants are those most in need of this funding. The rural fatality rate is about two times higher than the urban rate, according to the 2022 National Roadway Safety Strategy, disproportionately impacting people who are Black and Native American.

Transportation department officials point to data showing they’ve sent about half the grants to rural areas, which the agency defines as any urban area with fewer than 200,000 residents. That means even mid-sized cities like Amarillo, Texas, and Gainesville, Florida, would be lumped in with the tiny Montana county Smith described.

However, that same data shows just one in five dollars has gone to rural places.

Many of these rural grants have gone to affluent small towns, including dozens that reported few or no traffic deaths. They include places that serve as vacation gateways, such as Boulder, Colo. (which won $23 million); Missoula, Mont. ($9.3 million); Burlington, Vt. ($1.2 million); Nantucket, Mass. ($460,000) and Key West, Fla. ($400,000).

Just one low-capacity rural county has managed to win an implementation grant: Modoc County, in the far northeast corner of California. The transportation department awarded nearly $13 million there to add bicycle lanes, crosswalks and speed controls around tribal areas.

That leaves hundreds of low- and medium-capacity counties without a cent of Safe Streets funding – even in places whose data would put them at the top of DOT’s scorecard – places like Gallup.

“If this was a white community, there would be so much protection of the people. But we are disposable,” said Anna Rondon, who frequently drives her pickup truck the 30 miles between Gallup and her home on Navajo land.

Her fiancé died and she escaped with crushed vertebrae when they crashed years ago on a narrow Navajo road. She said people around Gallup just don’t have the mental space to push for change.

“Our people are living in shacks … if you ask any of the folks here, they’re just wanting to live. To survive,” Rondon said, noting how many families in her county go hungry. Food insecurity here is the worst in New Mexico, state data show, with more than one in five people lacking consistent access to food.

“When you have a society like that, it’s hard to get people motivated.”

Why are so many dying in crashes near Gallup?

The average American county sees slightly more than one pedestrian killed per 100,000 residents each year, according to USA TODAY’s analysis of five years of federal data. For McKinley County, New Mexico, where Benson Daniels was hit in a crosswalk in downtown Gallup, it’s nearly 11 per 100,000.

Daniels knew all the shortcuts through Gallup’s streets and alleys. He never owned a car in his 73 years, so he walked everywhere, even delivering copies of a local newspaper on foot after retiring from his job cooking at a café off historic Route 66.

But cataracts had started to blur his vision, so he’d been asking for more rides from his sister’s granddaughter. One of the last things Brandy Grenier remembers doing with the man she called Grandpa Benson was taking him for a haircut in late 2021.

“And he was going on and on about how good he looks now, and that he was going to look good for the ladies at church. And that maybe now they’ll sit next to him,” Grenier said, chuckling softly.

A few days later, Grenier couldn’t help when Daniels asked her to run some errands on a cold December morning. She’d just tested positive for COVID-19.

“If you could wait a couple of days, let me see if I can get someone to take you,” Grenier remembers telling him. “But, of course, he did not wait.”

Later that afternoon, as Daniels slowly made his way across Aztec Avenue, an elderly driver didn’t see Daniels over the hood of his Chevy van until it was too late. Daniels was knocked to the faded crosswalk, smashing his head on the pavement. The Navajo elder suffered a traumatic brain injury and died in a hospital 10 days later.

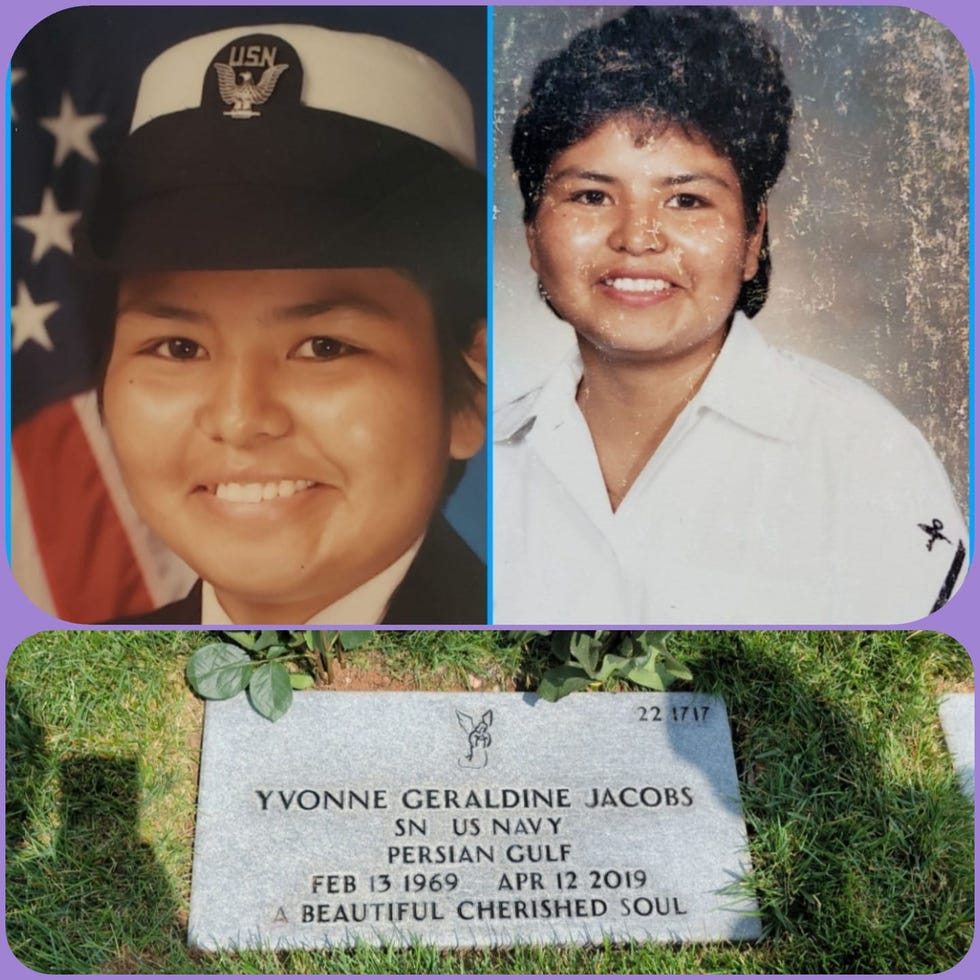

Daniels is just one of at least 40 pedestrians and more than 150 people overall killed in crashes across McKinley County in the last five years, according to DOT data. That list includes motorcyclist Janella Bryant, killed in 2020 as a drunken driver tore out of a liquor store parking lot, and Navy veteran Yvonne Jacobs, left to die on a dark bridge in 2019 when an intoxicated man drove away after hitting her. Multiple people were injured when a drunken man careened through a parade full of children performing traditional dances in 2022.

McKinley County checks the boxes for Safe Streets’ criteria of death count, death rate and an underserved population, yet its only funding so far covers tribal land an hour’s drive from Gallup and its crash hotspots. It’s getting a fraction of the $1.4-million planning grant the Navajo Nation is spreading across parts of several counties in Arizona and New Mexico.

Several things explain McKinley’s high fatality rate: Some 21,000 people live in its county seat of Gallup, but it’s the only place with a 24-hour hospital or Walmart in a county larger than Connecticut. The population balloons on weekends when people from outlying areas rumble into town in heavy-duty trucks to stock up on supplies or eat at a chain restaurant. Hitchhiking is still common, with people leaning across the shoulder of highways at all hours to wave a dollar or two, hoping someone might give them a lift. And dozens of trains roar through town each day, mere feet from pedestrians walking along Route 66.

State records show alcohol played a role in over half the county’s fatal crashes over the past decade. A local paper prominently features a “DWI Report,” noting that dozens of offenders have earned a second, third or even eighth charge for driving while intoxicated. But it’s not just the drivers.

“Most of our pedestrian-related incidents are involving inebriated, intoxicated individuals that are crossing the street in an unsafe manner,” said McKinley County Sheriff James Maiorano III, describing what he called “a generalized civil disobedience.”

“And it seems like it’s been a problem here forever,” he added.

Police reports say Yvonne Jacobs was intoxicated, walking home from a Gallup bar when a drunken man’s pickup truck slammed into her so hard it knocked her shoes off. Jacobs, a Gulf War veteran and single mother to a teenage son, died at the hospital less than an hour later.

The driver took a plea deal and never served time for Jacobs’ death, a common refrain among victims’ families seeking justice. Jacobs’ little sister, Cora Owens, took in her orphaned nephew and moved away, sickened every time she ran into the driver around their small town.

“I’ve never felt the word ‘hate’ in my life until I lost my sister, and I seen that person sit across from me in a courtroom. I have never felt so much darkness in my heart,” Owens said. “I don’t know if my sister was drinking. Whether she was, whether she wasn’t, she didn’t deserve to get hit either way.”

Recent road safety audits from the state have proposed ways to prevent Gallup’s deaths, from installing iron fencing along the interstate for $450,000 to constructing a pedestrian walkway under the railroad for $10 million.

A Safe Streets and Roads for All grant could fund these fixes or find other options. Pinellas County, Florida – home to vacation destinations like Clearwater and St. Pete Beach – won $2.5 million to cut deaths among drunken pedestrians and cyclists through education and enforcement campaigns, as well as more lights and physical barriers. Gallup, struggling with the same problem, didn’t even apply.

What blocks small places like Gallup from winning grants?

Competing for grants takes resources small towns often just don’t have, said Evan Williams. He leads the six-member staff of the Northwest New Mexico Council of Governments, which helps McKinley County and two neighboring counties coordinate on transportation, economic development and environmental issues.

Williams’ staff points out grant opportunities to the tiny tribal communities around Gallup and helps review applications, but most of these places can’t keep grant writers on staff. It’s often the village clerk or manager who might squeeze a grant application between typing up local meeting notices or driving the school bus, Williams said, leaving them little time to decipher complex federal guidelines.

And then there’s all the accounting paperwork to be done after winning a grant. That’s why Williams said they gravitate toward state dollars, which often require a smaller local investment and less-stringent reporting requirements.

“If you barely have time to write the grant, you’re never going to have time to manage the grant,” Williams said. “They could use all the grants in the world, but they don’t really have the capacity to manage them.”

The small city of Farmington, New Mexico, one county north of Gallup, is the only place in the state outside the capital of Albuquerque that’s applied for an implementation grant. It also struggles with above-average rates of alcohol-involved crashes and poverty, so traffic engineer Mark Hathcock tackled his first grant ever – by himself.

Hathcock requested $2.4 million to upgrade Farmington’s busy downtown intersections, but he said it was rejected because he didn’t supply enough data to justify the project.

“I felt like I’d covered everything they had asked for, but it wasn’t quite there. It was a huge learning curve,” he added.

Most federal grants set aside a small amount to help less-experienced applicants like Hathcock navigate the process, and the transportation department uses that to fund initiatives aimed at rural and tribal applicants. But, to get more funding into the hands of places like Farmington and Gallup, experts say agencies should push beyond hourlong webinars and invest in teaching fundamental grant writing skills that could level the playing field for underserved communities.

Without advocates, who demands change from leaders?

Hundreds of miles south of Gallup, past dozens of roadside descansos and a U.S. Border Patrol checkpoint, lies New Mexico’s second largest city, Las Cruces. There, in November, flickering candles cast shadows across photos of local pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists killed in what piano teacher Barbara Toth is calling the county’s “Deadliest Decade.”

Toth founded her advocacy group, Vulnerable Road Users New Mexico, after a teen driver in a pickup truck sent her husband Jim flying off his bicycle just blocks from their home in 2020. He survived, but the crash left him with debilitating spinal injuries.

It’s World Day of Remembrance for Road Traffic Victims, and Toth circulates through 70 people gathered for a memorial vigil, leaning over to share her flame.

“As we light the candles, we’re reminded that the victims we’re here to honor tonight were brothers. Fathers. Sons. Daughters,” she intones. “May who they are, and who they could have been, empower each and every one of us to make a difference.”

Las Cruces has done well for itself in the race for Safe Streets funding. The surrounding county, Doña Ana County, earned $400,000 to study its roads and create safety plans in the program’s first year, and the city won an additional $400,000 planning award in December 2023.

The death rate in Dona Aña County is four times lower – about 10 deaths a year per 100,000 residents, compared to 42 in McKinley County – but Dona Aña has gotten far more funding.

Headwaters Economics’ capacity index shows Doña Ana has significantly higher capacity than McKinley, which leaves room for more community engagement. Las Cruces has passionate advocates like Toth who raise awareness and petition leaders for change on traffic safety. Gallup does not.

Earlier this year, planning sessions for Gallup’s Master Transportation Plan lacked the impassioned speeches of Toth’s candlelight vigil. Several open houses and workshops sought public input last summer, but drew just eight people in all, according to the city’s website.

“There’s just like this ho-hum shrug of the shoulders all the time, like, ‘Hey man, that’s Gallup. People just get hit, you know,’” said Scott Nydam, a former professional cyclist who founded Gallup’s Silver Stallion Bicycles and Coffee. He says it’s the only bike shop serving the Navajo Nation, and his staff partners with local schools to get Navajo kids on mountain bikes.

In Las Cruces, Ashleigh Curry organizes walks to demonstrate road safety for elementary school students and their parents as the city’s Safe Routes to School coordinator. She and other local advocates pointed out that several cities across New Mexico already have road safety plans, often gathering dust on shelves.

Those plans won’t save lives, they say, if they never advance into additional projects to fix dangerous streets.

“If we truly, as a state and as a city, want to see a difference, we need to have a whole team of people who are working on this,” Curry said. “But we also need to follow the plans that we have.”

Over the next three years, the transportation department will award the remaining $3.3 billion in Safe Streets funding. That means more opportunities for hard-hit communities to turn their plans into action.

Kristin Smith, the Headwaters Economics researcher, said she’s encouraged that more federal grants have been earmarking money for rural and tribal communities. She said doing so disrupts patterns built through years of systemic disinvestment, improving people’s lives.

Safe Streets, though, has no such quotas – putting the have-nots at risk of falling further behind.

“Not only are those places missing out on really critical funding to improve the safety of their residents, but they’re also missing out on economic development,” Smith said. “If we keep this cycle going and keep repeating these patterns, we just polarize the country even more.”