The austerity package stemming from an adverse Constitutional Court ruling, Peter Bofinger writes, defies logic.

Last month the Financial Times quoted a chipmaker saying: ‘Germany is not just the sick man of Europe, it turns out it is also the dumb man of Europe.’ That sounds exaggerated, but the austerity package announced by its government a week later represents anything but a smart policy.

The package was made necessary by a ruling in mid-November by the Federal Constitutional Court. The court had ruled that the planned financing of the so-called Climate and Transformation fund with unused credit authorisations from the pandemic year 2021 was incompatible with the constitution.

The only way out would have been to invoke the emergency clause of the Schuldenbremse (debt brake) for 2024, as in the years 2020 to 2023. Enshrined in the constitution, this limits the federal budget deficit to 0.35 per cent of gross domestic product; in emergency situations, however, it can be suspended by a majority vote in the Bundestag.

But the Free Democratic Party, the junior partner in the Ampelkoalition (traffic-light coalition) with the social democrats and the Greens, was not prepared to countenance this. The resulting measures are counterproductive in every respect.

Pro-cyclical policy

The German economy has been chronically weak since the fourth quarter of 2022, GDP falling by 0.3 per cent last year. Nor is the outlook for 2024 good: in December’s ifo Business Climate Index, companies registered extreme pessimism about the current climate and expectations.

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

It would thus have been helpful if the government had stimulated the economy with expansionary measures. The austerity package instead provided a negative fiscal impulse of around €30 billion. Although not comparable in scale, it is reminiscent of the pro-cyclical policy pursued by Heinrich Brüning as chancellor between 1930 and 1932, which paved the way for National Socialism.

The measures adopted are also problematic from an anti-inflation point of view. The price per tonne of carbon dioxide has been raised from €30 to €45. A planned government subsidy of €5.5 billion for transmission-grid fees has been cancelled, leading to an increase in electricity-grid fees for residential customers of around 25 per cent. These measures are accompanied by other increases in indirect taxes in 2024: the rate of value-added tax on gas and restaurant services, which had been reduced to 7 per cent, has been raised again to 19 per cent.

All in all, fiscal policy is exerting upward pressure on inflation. In an environment of gradual disinflation, such measures are counterproductive. They prolong what Isabel Schnabel of the executive board of the European Central Bank called the ‘last mile’ on the road to price stability. Last year, the International Monetary Fund promoted the concept of ‘unconventional fiscal policy’—measures with a dampening effect on inflation. The austerity package is the opposite.

Electric cars

The subsidy for electric cars was cancelled in the package. The plan for 2024 had been that buyers of new cars (with a net list price of less than €45,000) would receive a subsidy of €3,000 from the state. A matching manufacturer’s contribution of €1,500 would have resulted in an environmental bonus of €4,500.

France shows what a smart policy looks like. From this year the government subsidy, of €5,000-7,000, is only granted to electric cars with a production footprint of less than 14.75 tonnes of CO2. As a result, six Chinese-made electric-vehicle models have lost their EV subsidies: the Dacia Spring, the Tesla Model 3 and four SAIC MG models. And premium EV models are not eligible due to a price threshold of €47,000.

In addition, the French government has started a €100-a-month leasing scheme. It is intended for the less well-off 50 per cent of households, with a taxable income per household unit (one per adult, half per child) of less than €15,400. Drivers will also need to be gros rouleurs (major users), who drive more than 8,000 kilometres per year, or live more than 15km from their workplace, to which they need to drive using their own car.

By no longer offering any incentive, the German government is not only making it more costly for consumers to buy electric cars. It is also harming the domestic automotive industry, especially Volkswagen, which is already struggling with the transition to electric mobility.

Carbon pricing

To many German economists, ending subsidies for electric vehicles is a good thing. In their view, the only adequate instrument for climate policy is the pricing of CO2 emissions.

But is the increase in the CO2 price for 2024 justified as incentivising energy savings? In 2019, when the government decided on the price path for 2021 to 2026, market prices for gas, petrol and diesel were much lower than today; today’s market prices, had they come about through raising the carbon price, would imply the latter had been hiked to €130-150 per tonne. In 2019 one of Germany’s leading climate economists, Ottmar Edenhofer, identified a CO2 price of €130 by 2030 as adequate. In other words, consumer prices for gas, petrol and diesel are today much higher than would be required from the perspective of climate policy.

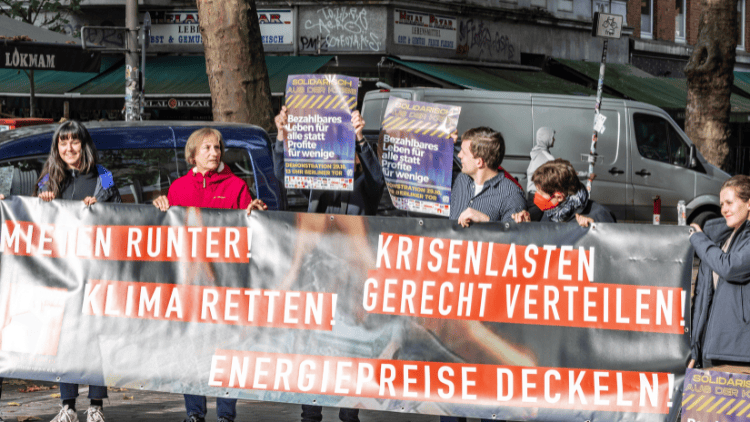

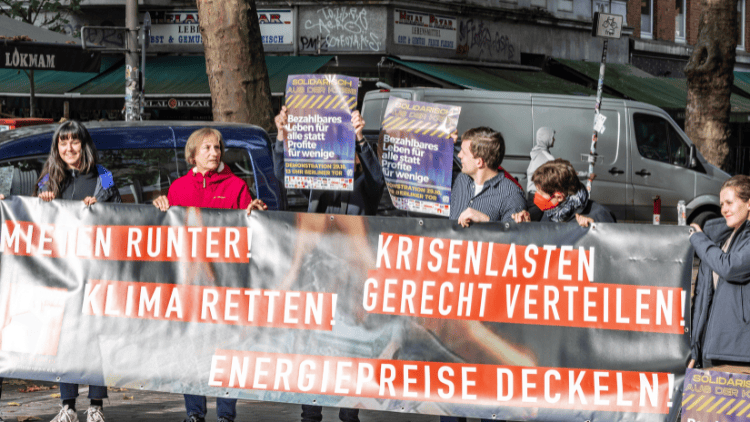

In addition, it is largely undisputed that the state should return the revenue from carbon pricing to its citizens on a per capita basis (‘climate money’). Due to the financial difficulties caused by the Schuldenbremse, this is not possible, which leads to resentment among citizens who rightly feel they have to pay too much for energy.

Relying one-dimensionally on the instrument of CO2 pricing is anyway politically dangerous, as many German citizens will be unable to substitute fossil energies by renewables. Think of low-income households living in rural areas because of high rents in cities. Because of inadequate local transport they have to commute by car but they cannot afford an electric car—the French approach shows how to design a smart solution to this problem. Too high energy prices without a return of the tax revenue to the citizens and the abolition of subsidies for electric cars is very risky, given the growing popularity of the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

Strategically important company

The Climate and Transformation fund was supposed to finance extensive, and thoroughly needed, modernisation at Deutsche Bahn, the rail network. Following the Constitutional Court’s decision, alternative funding must now be found.

One solution being discussed is sale of the highly profitable logistics group DB Schenker, a subsidiary of Deutsche Bahn. ADQ, one of the three sovereign-wealth funds of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, has been mentioned as a possible investor.

This is not without its problems: Schenker supplies the German armed forces and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, among others. Is it a wise policy for the German state, which can currently take on long-term debt at an interest rate of barely more than 2 per cent, to sell a strategically important and profitable company to foreign investors, just because it has to adhere to the ‘debt brake’?

Land of enlightenment

It is difficult to escape the constraints of the Schuldenbremse, but in view of the growing strength of the AfD one has to ask why it is not possible to shape a good economic policy for Germany enjoying a consensus among the democratic parties. As even conservative economists are now asking for a reform of the debt brake, one should not give up hope.

After all, Germany is the land of enlightenment. And what is now required in economic-policy thinking can hardly be better formulated than by Immanuel Kant in 1784, in his essay ‘What is Enlightenment?’:

Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity [Unmündigkeit]. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without another’s guidance. This immaturity is self-imposed if its cause lies not in lack of understanding but in indecision and lack of courage to use one’s own mind without another’s guidance.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal