Public investment has been skewed towards the military in the last decade when a much wider array of threats are in evidence.

The concept of security has been transformed over time, from a narrow focus on military aspects to a broader perspective encompassing various dimensions. Mary Kaldor pioneered the idea of ‘human security’, placing individuals and their needs at the core. This holistic approach takes in environmental, health and economic security as interconnected facets.

The multidimensional understanding of security gained global recognition from the United Nations in 2012 and it has been adopted by scholars of European Union foreign policy. Today, numerous states (including Spain and Germany) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization have incorporated non-military threats, such as pandemics and climate change, into security and defence frameworks, in light of their interdependence and of the costs they incur and the victims they cause.

Public expenditures

Recently, the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) initiated research to evaluate the alignment of public resources with national security priorities. Now a study promoted by Greenpeace offices in Germany, Italy and Spain, using NATO and Eurostat data, delves into the dynamics of military and other public expenditures, and their impact on output and employment. It has three main findings.

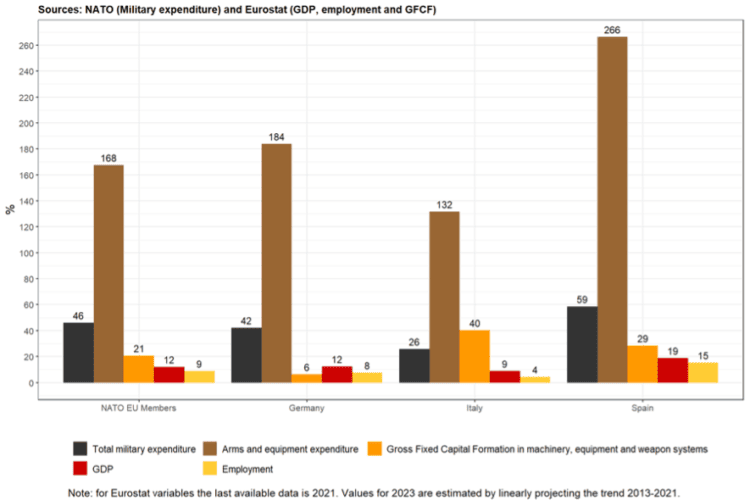

First, between 2013 and 2023, military expenditure in NATO EU countries increased in real terms by 46 per cent: in Germany by 42 per cent, Italy 26 per cent and Spain 59 per cent. In all cases the increase was mainly due to acquisition of arms and equipment: in 2023 arms expenditure in NATO EU countries reached €64.6 billion (up 168 per cent over a decade), with Germany tripling its spending to €13 billion, Italy reaching €5.9 billion and Spain €4.3 billion. EU imports of arms (based on SIPRI data) jumped as well, tripling between 2018 and 2022.

Secondly, real gross domestic product meanwhile rose modestly in 2013-23 by 12 per cent (just over 1 per cent per year on average) and employment by 9 per cent. The growth of military spending was is in stark contrast to the stagnation of EU economies (Figure 1).

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

Figure 1: changes in military expenditures and economic performance, 2013-23 (%)

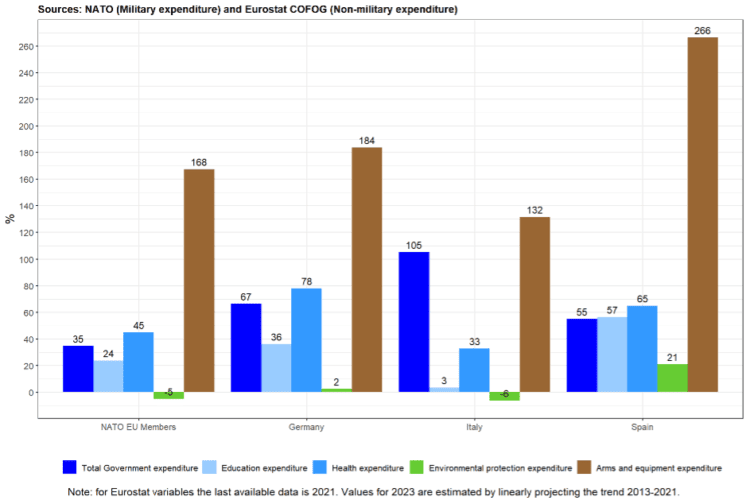

Thirdly, total government expenditures in NATO EU countries increased over the decade only by 20 per cent in real terms (about 2 per cent per year on average), with lower increases still in education (12 per cent) and environmental protection (10 per cent), albeit higher in health (34 per cent). The contrast with military expenditure is starker still if we compare capital investments: while NATO EU members were increasing their public expenditure on military capital by 168 per cent, such expenditure in the environmental-protection arena fell by 5 per cent (Figure 2). Yet a lesson from the pandemic was that investment in health and support for the civil economy was effective, according to economists and political scientists who therefore deem expansion of public investment essential.

Figure 2: real changes in arms expenditures and in investment in the environment, education and health, 2013-23 (%)

The asymmetry in public support for military as against other public expenditures has appeared in sharp relief in Germany. Last month the Constitutional Court blocked €60 billion in funds for the green transition which it held to violate the constitutionally embedded Schuldenbremse (debt brake), while exempting military expenditure from the same constraint.

Massive investments

EU-wide, there is a risk of a return to a policy of austerity, affecting social spending and public investment in economic and technological development when the EU needs to make massive investments—just as the United States and China are doing—in renewables and electric cars. Learning the positive lessons from the pandemic, a qualitative step-up is needed in investments for the environment.

One suggestion is to develop EU public infrastructures with research autonomy and their own scientific partners, able to capture industrial start-ups in dedicated hubs, allowing skills to be accumulated and exchanged. This should be in the context of mission-oriented public commitments, reducing uncertainty and ‘crowding in’ private investments.

Public investment needs to be balanced between industrial policy and military expenditures. As demonstrated by Greenpeace, the latter have low multiplier effects on output and employment. Using an input-output model, its study found that while in Germany, for example, €1 billion of public expenditure could create 11,000 new jobs in the environmental sector, almost 18,000 in education or 15,000 in health, similar military expenditure would bring only 6,150 new jobs. This is affected by reliance on imported arms and inefficiencies associated with the monopsonic nature of the arms market, governed by a cost-plus logic.

At the same time, there may be some advantages stemming from the volume, continuity and certainty of military expenditures (with the absence of business risk), the high research-and-development investments and mission orientation. Transferring these characteristics to other public investments—especially in renewable energies and clean transport—could enhance their multiplier effects in the green transition, particularly over the medium and long term.

Greater threats

Climate change or pandemics, moreover, pose even greater threats to the security of EU citizens and future generations than armed conflicts. According to Uppsala University, in 2022 there were 204,009 deaths in intra-state conflicts worldwide with 81,856 in Europe, due overwhelmingly to the war in Ukraine. Yet according to the World Health Organization, to date in Europe there have been 2.26 million victims of the coronavirus and 1.4 million deaths annually are linked to environmental risks, including pollution and climate change.

Reliance on weapons alone would hardly even solve some of the current military conflicts, which instead require a wide range of instruments, addressing the roots of conflicts and pursuing the rule of law in line with tradition of the EU security strategy. A strictly military response is certainly inadequate to address the gamut of security threats and a rebalancing of spending is necessary—supporting the economy and employment as well as human security.